From the time his daughter Cindy was diagnosed with a heart defect in the 1950s until the day he died more than half a century later, Kenneth Winn carried in his wallet a special piece of paper.

As the years passed, the paper grew tattered; the sketch on it, more faded. But he held on to what her cardiologist had drawn for him – a way to understand, even at its most basic, why his little girl’s heart beat so quickly, why she sometimes turned blue, why even non-exertive playing wore her out.

And why groundbreaking surgery – one of the first in the country on a child her age – would save her life.

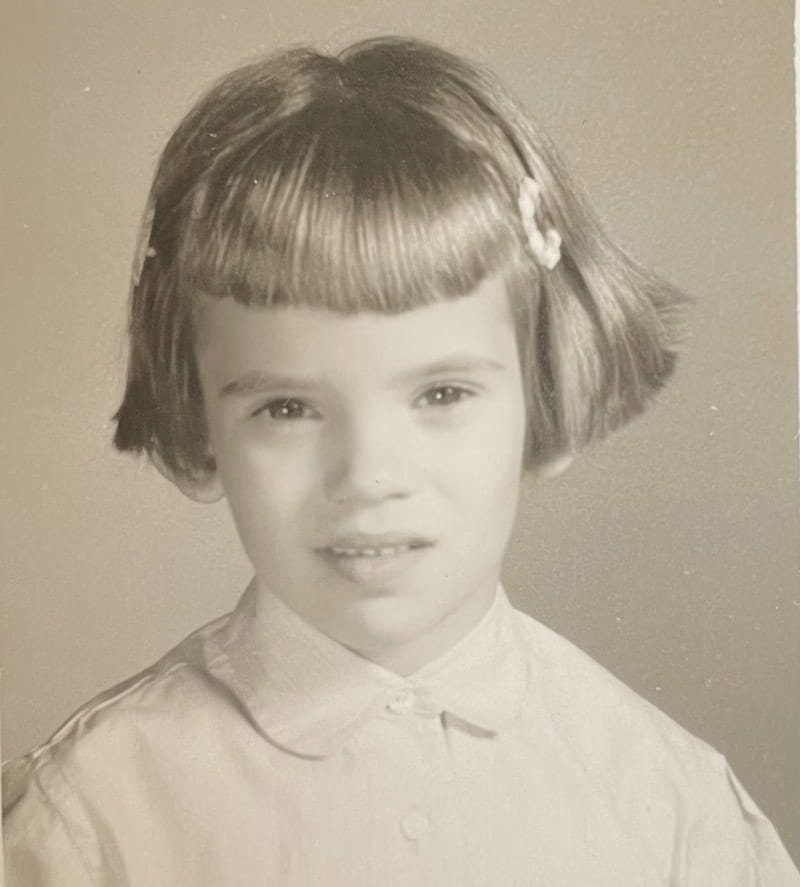

For the early part of her childhood, Cindy Allen-Stuckey was in and out of hospitals while doctors sought to find the cause of her symptoms. They ruled out pneumonia and cystic fibrosis. Finally, when she was 3, doctors at a children’s hospital in Indianapolis recognized her heart issues. The first was a heart murmur.

Soon after, she was diagnosed with an atrial septal defect and anomalous pulmonary venous drainage. Or, as her dad told her: “You have arteries on one side but none on the other, and a hole between the chambers.”

He then showed her the sketch her cardiologist had painstakingly drawn so her parents could understand what their little girl was undergoing. Cindy had surgery when she was 6. Had they waited any longer, doctors said, she likely would have been bedridden by age 12.

The surgery went well. Subsequent notes through months and years that followed (and which Cindy tracked down after an unexpected heart scare several years ago) tell how she was symptom-free and growing normally. But in the hospital immediately after surgery, recovery played out quite differently than it would have today.

In 2024, her parents would be able to stay with her. In 1956, visiting hours were limited to one hour every Sunday, and 20 minutes every Wednesday.

That was tough on her. When she came home after nine days in the hospital, she didn’t want to talk about that or anything else about the surgery.

“I’d been different from everyone else for six years and I didn’t want to be different again,” she said.

So, her parents didn’t speak of it either. In elementary school, she cringed when the circulatory system came up in health class and teachers talked about the heart. She avoided the topic as best she could.

She grew up, married for the first time at age 19, had a child, got her undergraduate and master’s degrees, and taught first grade – not coincidentally, to children the same age she was when she had surgery.

She told her first husband about the surgery once, but they didn’t talk about it again. When her son, Brandon Allen, was born, she made certain that doctors checked for every possible heart issue he might have. (He had none.)

She’s been married 36 years to her second husband, Tim Stuckey. “Somewhere along the way I told him I’d had heart surgery,” she said, “and that was probably the whole conversation.”

A few years ago, Cindy’s heart began racing. Tim took her to her physician, who gave her the all-clear, which a precautionary electrocardiogram confirmed. A technician, seeking as much background information as possible on her heart, tracked down the notes from her surgery decades earlier.

Cindy’s own research led to watching a documentary about the earliest heart surgery performed on children in 1944 at Johns Hopkins University. Turns out her surgeon, Dr. Harris B. Shumacker Jr., trained under that surgeon and performed the first heart surgery at Riley Children’s Hospital in 1956 – the year Cindy had hers.

“It made me realize this was a huge event for me and for Riley Hospital,” she said. “I truly feel like a walking miracle.”

Around then, Cindy learned one other significant piece of information: The times she felt abandoned by her parents after surgery, which included one day they didn’t show up at all – the empty feelings that followed her into adulthood – weren’t because they didn’t care.

“I finally asked my mother why they weren’t there,” Cindy said. “She started to cry and told me the doctor said I was so upset when she and my dad left that he thought it best they not come at all.”

That was a breakthrough, one that – along with so many other thoughts and experiences – she shared with Kathy Adams, her friend since 1988. They discovered that each had surgery as children in the mid-1950s; Adams’ surgery was on her eye.

“We talked about the phrase ‘wounded healer’ to describe people who have been through a lot and now feel their mission is to help other people,” Adams said. “That is Cindy. She’s a wounded healer. She helps others reach their highest potential.”

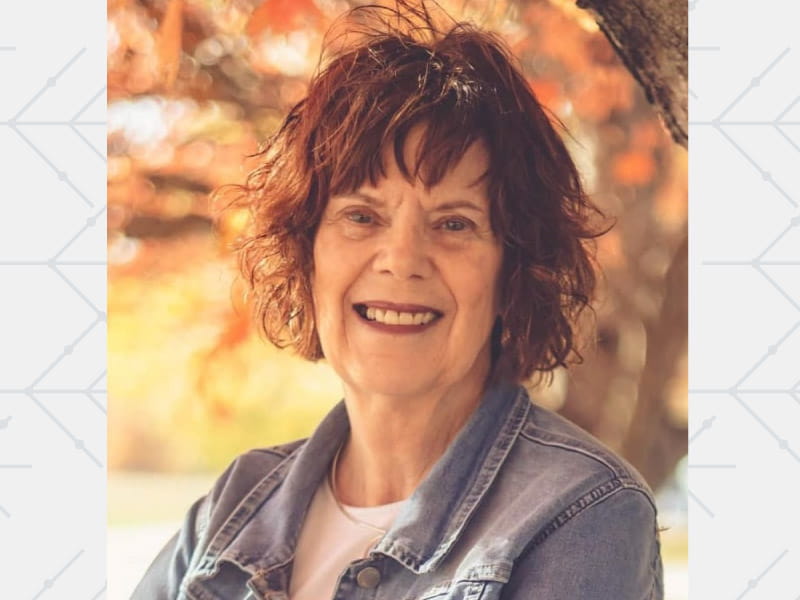

Cindy has written a book that includes how her heart challenges as a child helped shape her. She is also a motivational speaker who talks about how what she endured helped her become the person she is today.

She ends her talks by asking audience members to reach under their seats.

“I’ve placed a sketch of my dad there,” she said, “holding the piece of paper with my heart drawn on it.”

Stories From the Heart chronicles the inspiring journeys of heart disease and stroke survivors, caregivers and advocates.