Before their baby was born, doctors had warned Stephanie and Justin Cervantes that his color at birth would be blue.

Still – despite knowing he had heart issues, despite months of monitoring him in utero, despite endless conversations about his future – how can parents possibly prepare themselves for that?

“I didn’t even think he was alive,” Justin said. “He didn’t cry. He didn’t do anything. They rushed him out of the delivery room.”

That, he said, is when everything hit him.

“I was scared,” he said.

The problems began halfway through the pregnancy. During a routine anatomy scan, their baby boy didn’t show his stomach.

Stephanie and Justin didn’t worry, though. It seemed like nothing more than bad timing. Stephanie even joked, “I started doing jumping jacks to get him to move so the technician could see it.”

A few days later, another scan did show the stomach. In the wrong place.

His stomach and other nearby organs were in his chest cavity. They’d pushed through a hole in his diaphragm called a congenital diaphragmatic hernia. That wasn’t the only big discovery.

A fetal echocardiogram showed their son also had tetralogy of Fallot, a congenital heart defect marked by four problems. This was why the doctors braced Stephanie and Justin for their son to be blue at birth.

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia, or CDH, is rare. So is tetralogy of Fallot. Stephanie compares one person having both as being “like getting struck by lightning twice.”

They decided to name the baby William, in honor of her dad; he’d died of a heart attack a month before she found out she was pregnant. Justin’s dad had a heart attack while in his 50s and had open-heart surgery. But baby William’s issues were not inherited; they just happened.

William arrived in February 2021. Two days later, he had his first surgery; to correct his CDH, doctors moved his organs where they belonged.

While he recovered, Stephanie was released from the hospital and returned to her Houston home. An unusually severe winter storm hit the next day. Not only were Stephanie and Justin unable to get to the hospital for several days, they couldn’t even call to check on William. Power was out across Texas, leaving their cellphones useless, and they had no landline. They endured that agony for four days until finally reaching a nurse. It was another day before they were again able to visit their baby.

Tetralogy of Fallot is repaired through a series of operations. William’s first surgery was postponed several times because he kept developing pneumonia.

At 2 months old, he underwent a 14-hour surgery. During his recovery, Stephanie and Justin each were required to separately spend 24 hours in the hospital to make sure they knew CPR, how to give their baby his medications, what symptoms of distress to look out for, and how to treat anything that came up.

Around 4 months, William came home. The joy was muted by fear – “terrifying,” Stephanie called it. “I don’t think I slept for weeks,” she said. “I was obsessed with his oxygen saturation and his heart rate and had no nurses around to assure me everything was fine.”

For the most part, it has been.

Challenges have included a bout last August with RSV, or respiratory syncytial virus, that landed him in the hospital. He was slow to learn how to eat because of how long he spent getting fed through a tube in his stomach. In November, he had his second heart surgery. He remains on oxygen.

“He may not be an Olympic swimmer,” Stephanie said, “but he’s expected to live a very full, very active life.”

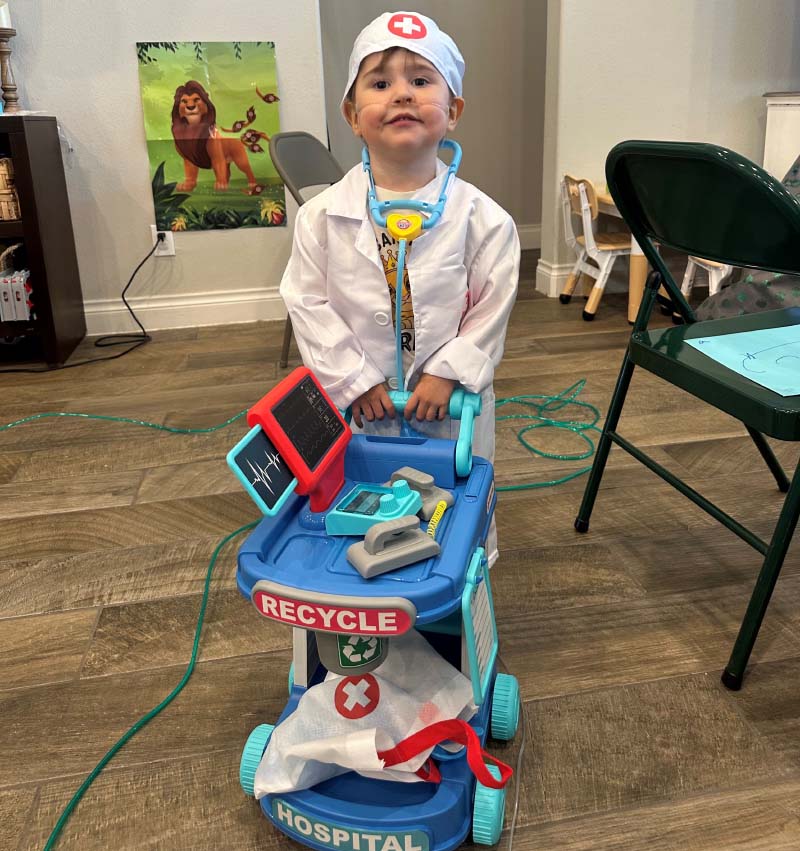

Now 3, William takes one medication for acid reflux, two for his heart, a baby aspirin and a multivitamin, all given through his feeding tube. Eventually, his parents said, he’ll be weaned off those as well as oxygen.

“He’s definitely taught us what strength is,” Stephanie said. “He’s been through more in three years of life than most adults go through in their entire lives.”

Stephanie and Justin like taking William to a kids’ gym – and he loves it, too. He also gets excited at a playground; like the healthiest of kids, he wears himself out having fun on the equipment. His speech is exceptionally good and, his parents said, he’s quite the charmer.

“He has the biggest personality,” Stephanie said. “All we wanted was for him to live at least a normal life, but I think he’s meant for bigger things. He leaves an impression everywhere he goes.”

Stories From the Heart chronicles the inspiring journeys of heart disease and stroke survivors, caregivers and advocates.