“Thank you for your service,” military veterans often are told. For about a million, it might be time to add, “and also for your science.”

The Million Veteran Program, a Department of Veteran Affairs research effort underway since 2011, is built on veterans who give a little blood and a little time. Now close to enrolling its milestone millionth volunteer, it has compiled “a treasure trove” of genetic information, health records and lifestyle details, said Dr. Sumitra Muralidhar, the program’s director.

The science could have far-reaching effects. “I have goosebumps when I think about it, what it can do in the future, and how long-lasting it will be,” said Muralidhar, who helped create the program and works in the VA’s Office of Research and Development in Washington, D.C.

And the research will help more than veterans, said Dr. Philip Tsao, one of the program’s co-principal investigators.

“For better or for worse, the health issues associated with veterans greatly overlap with the civilian population,” said Tsao, a professor of medicine at Stanford University and associate chief of staff for precision health at the VA Palo Alto health care system in California. “Whether that be heart disease, diabetes, stroke or cancer, they’re just as prevalent, if not even more prevalent, in the veteran population.”

Why would scientists need a million veterans’ data? When Muralidhar and others envisioned the program, they wanted to enable the study of “any condition that we might see among veterans,” she said. “So, we need very large numbers of people.”

That they have, said Dr. J. Michael Gaziano, another of the program’s founders and a co-principal investigator. With 999,500 participants and counting, “it is the largest health system-based mega-biobank in the world,” said Gaziano, who also is a cardiologist with the VA Boston health care system and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School.

The UK Biobank, which may be the best-known similar effort, has made genetic and health data from 500,000 people available. In the U.S., the All of Us program also has a goal of 1 million people. About half that number had completed its initial steps as of October.

For context, the Framingham Heart Study, which started in 1948 and has enabled generations of cardiovascular research, has information from about 15,000 people.

Any veteran can take part in the Million Veteran Program. Each fills out an extensive health questionnaire and offers a blood sample, which can be used to extract about 765,000 markers from their DNA, Muralidhar said. Some samples get a more extensive analysis that extracts 3 billion gene pairs.

On top of that, about 400,000 vets have answered a detailed food survey, making it the largest nutrition database in the world, Muralidhar said.

The numbers get gaudier. The Veterans Health Administration, the largest integrated health care system in the U.S., has electronic health records dating back decades, and that information is linked in, along with information from veterans’ years of active duty.

“We get data about people’s deployments,” Gaziano said. “We get data about health conditions that developed when they were in the military. There is even physical exam information about when patients were enrolled in the military.”

That adds up to 6 billion notes from physicians and 12 billion lab records, Muralidhar said, who added that data privacy is “one of our highest priorities.” Researchers are provided access only to coded or anonymized data.

The ability to combine genetics data with electronic health data from a million people allows researchers to dissect the genetic underpinnings of disease in a way that was “unimaginable” two decades ago, when the Human Genome Project was being completed, said Dr. Kiran Musunuru, director of the Penn Cardiovascular Institute’s Genetic and Epigenetic Origins of Disease program. He hasn’t worked with the veterans’ data, but many colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia have.

“In the past, our understanding of disease was largely limited to cases where mutations in a single gene drove the disease process,” he said. “Thanks to studies powered by the Million Veteran Program and other massive databases, we now have a much better idea of how combinations of genes influence diseases, how those genes interact with environmental factors to predispose or protect people from diseases, and how we can develop better diagnostics and therapeutics for the diseases.”

The amount of data is so massive that Million Veteran Program researchers have used the Department of Energy’s most powerful supercomputers – the kind used to model nuclear reactions and climate change – to crunch it.

You don’t need to be a math major to appreciate some of the findings, however.

Although it’s taken a dozen years to hit the million-veteran milestone, Million Veteran Program researchers have used information from earlier participants to publish more than 350 studies, and the data has been used by many others, Gaziano said.

Those publications have:

– suggested that yogurt affects cholesterol levels in healthy ways that are distinct from other dairy products.

– identified 18 new genetic markers for peripheral artery disease, or PAD, a narrowing of the arteries that carry blood away from the heart. That finding made the list of the American Heart Association’s top heart disease and stroke research advances of 2019.

– revealed new genetic links to the risk of post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, and suicide.

Tsao used a study on abdominal aortic aneurysm, a potentially fatal ballooning of the artery that supplies blood to the belly, to highlight the program’s abilities.

Tsao was senior author on the study, which appeared in the journal Circulation in 2020. Prior work had shown that such aneurysms run in families, he said, but few had looked at the genetics.

With the Million Veteran Program, “we were able to go into electronic health records and immediately find” more than 7,600 cases of the disease. “So immediately, in that situation, we had more disease cases than had ever been reported in genetic studies,” Tsao said. The study revealed 14 new genes related to abdominal aortic aneurysm.

The program’s designers acknowledge limits to a study based on veterans.

It’s representative of the VA users, which is dominated by older veterans, Gaziano said. It’s at least 90% men. It’s only 8% Hispanic and 1% Asian – comparable to the veteran population but at levels far below the overall U.S. population.

But 18% are Black, giving the program the largest Black cohort of any global genetic research program. Gaziano said that given its size, even smaller groups are represented in large numbers. “Ten percent women is still 100,000,” he said.

Musunuru said that the program’s relative diversity is a strength, as did Tsao, who said that most genetic studies are based on data from people of European descent.

Tsao is excited about the broad range of studies the program will enable. Future researchers will be able to contact study participants for follow-ups.

That means people found to have a gene related to cholesterol, for example, could be asked to try different diets.

“You can start to find out what the effect of lifestyle is layered on top of your genes,” Tsao said. “It just opens up a whole new arena of research that heretofore hasn’t happened.”

Gaziano said that in the months ahead, the program will release findings from a supercomputer-powered look at how 50 million genetic variants are related to 2,000 diseases, which he deemed “incredibly exciting.” Other studies might identify new uses for existing drugs or help doctors select the best blood pressure medication to match an individual’s genetics.

The program also hopes to unravel concerns specific to veterans. In addition to work on PTSD, Muralidhar said, a task force is looking at ways in which the program’s data can be used to study the effects of how military-related exposures – including the “burn pits” of the Gulf War – might affect veterans’ DNA. “That is just in very early stages,” she said.

The program has a special responsibility to understand veterans’ concerns, Gaziano said. Like many at the VA, he said, his connection to them is personal. His father served as an Army doctor early in the Vietnam era, and his son is an Army Ranger who served in the Middle East and Afghanistan.

Gaziano has worked with other large studies and biobanks and said questions often come up about how to pay people to come in to give samples or reward them for staying connected. He said veterans just ask, “Is this going to help other veterans?” He tells them they hope so. “And they say, ‘Well, then I’m in.'”

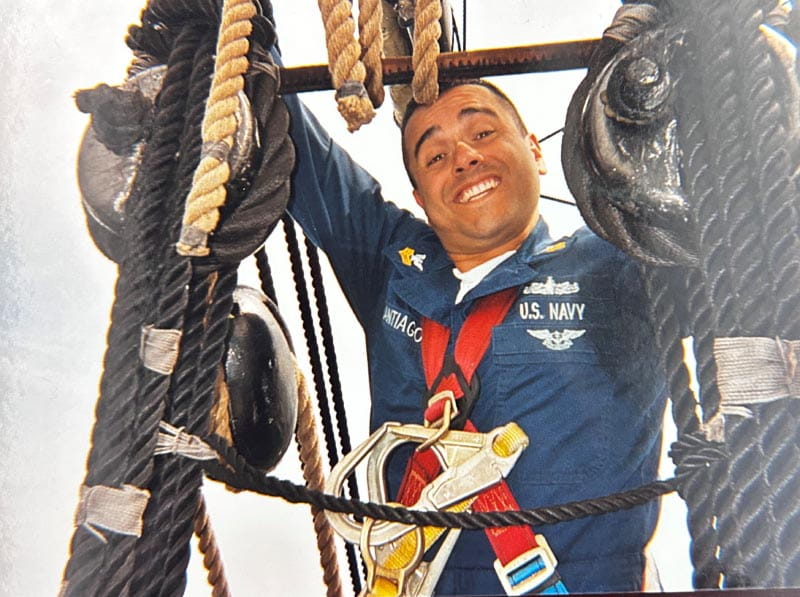

Veterans can enroll at 67 sites nationwide or online at mvp.va.gov. One of the first to do so was Rob Santiago, a 20-year Navy veteran who lives in Boston. His span of service included wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and closed aboard the world’s oldest commissioned warship, the USS Constitution.

Now the city’s commissioner of veterans services, he was working for the VA when the Million Veteran Program got started.

The decision to sign up was a “no-brainer” once he learned that the information he shared could help another vet, he said. A veteran’s attitude is, “We take care of each other. And we do what we can.”

Gaziano knows that attitude well. “They’re wired for service,” he said. “As teenagers, they decided to serve their country. And they continue to serve. They continue to help each other.”