If you’re looking for a tennis court anywhere in the country, the “Find a Place to Play” page on the United States Tennis Association’s website can help.

Just plug in a location as a starting point. You can narrow the search by surface type, court size, number of courts and whether a facility is public or private. You can even aim for places with indoor courts, lights, a hitting wall, coaches, a pro shop and/or Spanish-speaking instructors.

Missing from that list? Whether the facility has anyone trained in CPR, and whether the facility has an automated external defibrillator, or AED.

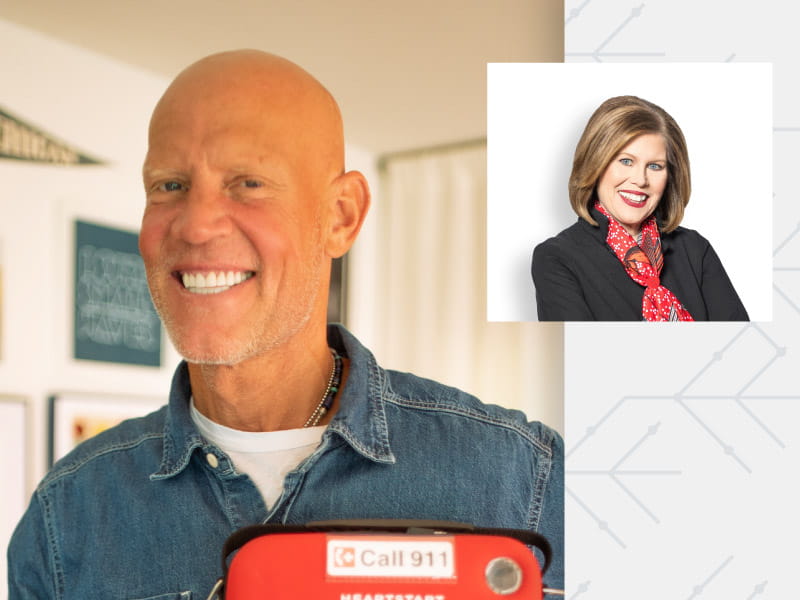

Those options will be added soon if former Grand Slam doubles champion Murphy Jensen gets his wish.

February is American Heart Month and this February my organization – the American Heart Association – is turning the focus to restarting hearts that have stopped because of cardiac arrest. We’re encouraging everyone to become a potential lifesaver by learning CPR and how to use an AED.

The importance of these skills surged into public consciousness last month when Damar Hamlin of the Buffalo Bills went into cardiac arrest during an NFL game. He survived in part because he received immediate CPR and because his first responders used an defibrillator.

In October 2021, something similar happened to Jensen.

He was at a resort in Colorado, playing an exhibition tennis match against the facility’s new head pro – his big brother Luke, who’d also been his longtime doubles partner. In 1993, they went from unseeded to French Open champions, doing so with so much flair that they became mainstream stars, such as getting profiled in People and Rolling Stone magazines.

Both are in their 50s now, with Murphy arriving in Colorado in perhaps the best shape of his life. Ready to blast a serve at Luke, Murphy flashed a big smile, then tossed the ball in the air. The ball fell, then so did Murphy, tipping over backward stiff as a statue.

Sitting courtside, two trained first responders saw Murphy’s eyes close mid-serve. They began moving toward him even before the back of his skull slammed into the hard court. When they got to him, he wasn’t breathing and had no pulse.

Within seconds, a doctor joined them. The trio started CPR while Luke ran to grab an AED off a nearby wall. He knew it was there because, the day before, as part of his new-employee training, one of those first responders had pointed it out to him.

Once Murphy’s heart was stabilized, he was placed into a medically induced coma to let him heal from the trauma. Family, friends and fans waited anxiously for several days to learn whether he’d sustained any brain damage. He came out of it OK, surely aided by his strong overall fitness, then headed home to start another chance at life.

For Murphy, it was the latest in a series of do-overs.

Fame lured him into a life of misusing drugs and alcohol. He cycled between sobriety and recovery for many years until a summer day in 2006, when he finally understood, “All the things I love and care about most I’ve hurt through drugs and alcohol.” He’s remained sober ever since.

By the time Murphy embraced long-term recovery, heart disease was already taking a toll on him. He had myocarditis, a condition that probably came from the bad luck of a virus working its way into his heart.

First, it caused heart failure. Then came an irregular heartbeat that needed intervention. He wound up getting two ablations, procedures that essentially burned away the problem spots. Exhaustive tests showed that all was well. Until the power went out in Colorado.

Meanwhile, in 2012, Murphy played in an event hosted by the Steven M. Gootter Foundation, a charity that raises money to put AEDs in schools, YMCAs, churches, synagogues and law enforcement vehicles in Arizona. Soon, Murphy became the organization’s lead ambassador.

Yes, that’s right – Murphy began touting CPR and AEDs nearly a decade before they saved his life.

Flash to late 2021, when Murphy returned to his suburban Seattle home to begin recovering from his cardiac arrest.

His heart was now the least of his concerns. In the hospital, he received an implantable cardioverter defibrillator, or ICD. The device is essentially an internal AED, always on patrol to regulate his heartbeat should it get out of whack, or stop, ever again.

Instead, the rest of his body needed help, mostly because when his heart stopped, Murphy – who is 6-foot-5 – fell a long way in a completely defenseless position.

He fractured his skull in five places, cracked four teeth and lost most of the hearing in his left ear. Even months later, persistent concussion symptoms left him sensitive to light and sounds. He spent many days in the dark and quiet of his basement office, alone with his thoughts.

His sobriety remained rock-solid, mainly because he’s devoted his life to maintaining his recovery and to helping others treat their substance use disorder. What nagged at him was the question, “Why am I still here?”

“We’re going to find out,” his therapist told him.

Although Murphy is an intensely outgoing guy – a megawatt personality who was among the first stars on the Tennis Channel – he’s also deeply spiritual. His daily ritual includes an emphasis on gratitude. His family also thrives on a mantra he came up with while working through his substance use disorder and mental health challenges: “Always leave room for a miracle.”

He began reflecting on how lucky he was. Sure, bad luck marked his journey. But consider how lucky he was when his heart stopped. It happened in public (not a few hours earlier, when he was swimming alone with his 4-year-old son), in front of people trained in CPR and with an AED nearby. He was alive because every link in that chain of survival was firmly in place when he needed it. The confluence of events is why his pals in the tennis world started calling him “Miracle Murphy.”

Around the time Murphy grasped his good fortune, he heard about a man whose heart stopped while playing tennis at a facility in Princeton, New Jersey. The man – a father of three in his 40s – received CPR from two people who happened to be there for a youth tournament. One of them, a doctor, sent his son to fetch the facility’s AED. The son returned empty-handed because the facility didn’t have one. Chest compressions kept the man alive long enough to get him to the hospital. He died days later.

Similar circumstances. Different outcomes.

The conversation left Murphy in tears. Soon after, he found his new purpose.

He would push even harder to promote CPR training and expanded access to AEDs. And, Murphy being Murphy, he came up with an audacious goal. He wanted to put an AED at every tennis court in the country.

More than a year later, the plan is in motion, moving slowly but gaining momentum.

He started with his own actions. Now that he’s back to playing exhibition matches, he makes sure the facility has an AED. When he arrives, he asks where it is.

“Too often they tell me, `I think it’s at the pool’ or `It might be in the gym,'” he said. “That’s not good enough. Organizations need to educate their people. There needs to be a process in place to make sure everyone knows where it is. They need to know what to do and who knows CPR.”

For the first anniversary of his cardiac arrest, Murphy shared his story at length with Tennis.com and American Heart Association News. That led to more people and places reaching out to join his crusade.

“Thousands of people send comments, emails, call me,” he said. “They’ll send me pictures of AEDs at their clubs. I love it!”

Murphy is now dedicated to working with the AHA to spread the word about AEDs and CPR training. (The training begins with this simple lesson: If an adult isn’t breathing, push hard and fast in the center of their chest, preferably to the beat of the song “Stayin’ Alive.” While you’re doing that, tell someone to call 911.)

He’s also ramped up his work with the Gootter Foundation – or, rather, as it’s now called, the Gootter-Jensen Foundation. The organization rebranded in his honor and widened the scope of its mission from its home base to the entire nation.

Next on his wish list is a meeting with the USTA. He wants to begin working toward adding the CPR-trained and AED options to the “Find a Place to Play” page. Better still, he hopes there will be a day when those options aren’t needed because every facility has CPR-trained employees and an AED.

“Even that is not my ultimate goal,” Murphy said. “The grand vision is to take this as far as I can take it. Congress should mandate that wherever a certain amount of people gather, there has to be an AED.

“I’m alive to be with my wife and sons because of the people who were there the day my heart stopped and because of the people who put an AED by that court. My way of thanking all of them is by being of service to everyone else.”

A version of this story appeared on Thrive Global.

If you have questions or comments about this American Heart Association News story, please email [email protected].