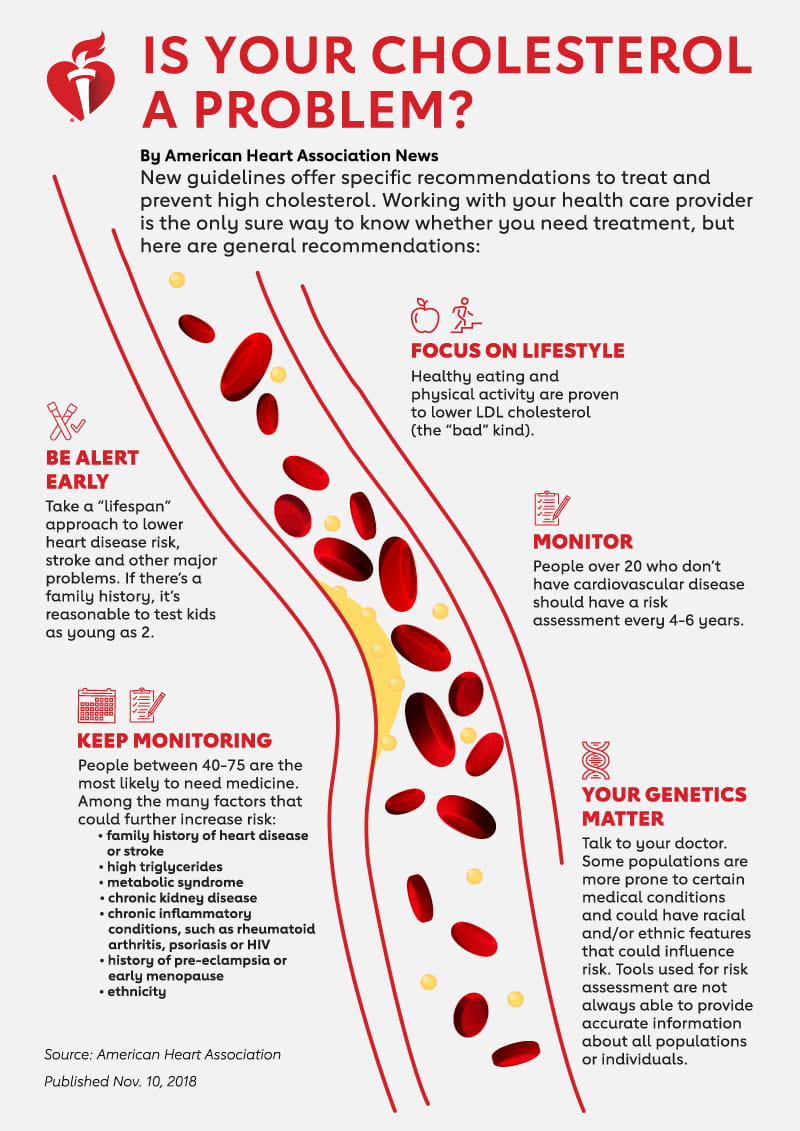

Exposure to high blood cholesterol over a lifetime can increase the risk for heart attack or stroke, and new scientific guidelines say managing this waxy, fat-like substance in the blood should be a concern for all ages.

The guidelines, published Saturday in the journal Circulation, are meant to help health care providers prevent, diagnose and treat high cholesterol. A panel of 24 science and health experts from the American Heart Association and 11 other health organizations wrote the guidelines’ science-based recommendations for people with very specific conditions and risks.

“The evidence is overwhelming,” said Dr. Scott M. Grundy, chairman of the guideline writing committee and professor of internal medicine at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. “Essentially no one says cholesterol is not important. The whole world now understands – it’s important.”

Nearly one of every three American adults have high levels of LDL, the so-called “bad” cholesterol that contributes to fatty buildup and narrowing of the arteries, called atherosclerosis. Global and U.S. studies have suggested the optimal level is less than 100 mg/dL (milligrams per deciliter) for otherwise healthy people, and research trials have shown people with an increased risk of heart disease are less likely to develop heart disease and stroke when given drugs to lower elevated levels of LDL.

“The LDL cholesterol particle is really the central molecule involved in the biology of this disease,” said Dr. Donald Lloyd-Jones, a writing committee member and chair of the department of preventive medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago. “It’s important to understand the life course of exposure and the context of other risk factors in which that is occurring.”

Along with well-established risk factors such as smoking, high blood pressure and high blood sugar, the guidelines suggest also looking at “risk-enhancing factors” such as family history and other health conditions to provide a better perspective of a person’s overall risk during the next 10 years.

View text version of infographic.

The guidelines recommend doctors use a calculator to give a detailed assessment of a person’s 10-year risk for heart disease and to help create a personalized plan. For most patients who can’t control the condition with diet and exercise, a cholesterol-reducing drug called a statin can be used. For patients at very high risk, including those who already have coronary heart disease, stroke or very high cholesterol caused by genetic conditions, additional drugs called ezetimibe and PCSK9 inhibitors can be used.

“The truth about clinical medicine is there is no black and white. It’s all gray,” said Lloyd-Jones, a practicing cardiologist. “That’s why the emphasis in this document is making sure the patient and doctor are having well-informed discussions about the benefits and the potential risks of drug therapy. … If a patient has had a heart attack or a stroke, we know those people will benefit from a statin. When there is someone who hasn’t had an event, that’s when the decision is more difficult and a detailed and personalized discussion is very important.”

For people 40 to 75 years old without evident heart disease, the guidelines use four classifications of risk: low, borderline, intermediate and high.

When a patient is in the intermediate zone, and sometimes on the borderline, the guidelines suggest doctors have an in-depth discussion with patients about potential benefits of statin drugs, considering all risk factors. If uncertainty remains about whether to use a statin, doctors can consider delving further with a test called a coronary artery calcium, or CAC, screening. A CAC score is calculated based on taking a CT scan of the heart and determining how much calcium plaque is building up in the heart’s arteries.

For younger adults between 20 and 39, the guidelines emphasize a healthy lifestyle, maintaining a healthy diet and weight and exercising regularly, Grundy said.

Because of a lack of long-term research for this younger age group, statin recommendations are reserved for those at higher risk.

But Grundy said that doesn’t mean those patients should be ignored, because young adults with risk factors like high cholesterol often already show the first stages of atherosclerosis.

“We think doctors ought to pay more attention to young adults,” said Grundy, who is also chief of the metabolic unit at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Dallas. “If their cholesterol is high, they should try their best through the right kind of diet, keeping their weight down. … They might not need a statin, but they certainly need attention.”

Because of the potentially dangerous effects of a lifetime exposure to high cholesterol, particularly LDL, the guidelines suggest doctors consider selective screenings of children as young as 2 who have a family history of early heart disease or high cholesterol. In children without any known risk factors, doctors could recommend tests between the ages of 9 and 11 and then again between 17 and 21.

“That catches those with severe cholesterol disorders requiring early treatment with lifestyle changes or, rarely, for those 10 and older, medication,” said Dr. Sarah D. de Ferranti, chief of outpatient cardiology and director of preventive cardiology at Harvard Medical School’s Boston Children’s Hospital. “It’s important that, even at a young age, people are following a heart-healthy lifestyle and understanding and maintaining healthy cholesterol levels.”

It’s a “lifespan approach” to thinking about cholesterol, said de Ferranti, who was also on the guideline writing committee.

“As a pediatrician, this comes naturally since we are always aiming to deliver our patients into adulthood with the best chance possible for a long and healthy life,” she said. People at age 20 with normal heart health have a better chance of making it to 50 with normal cardiovascular health factors.

It’s a reality that Carl Korfmacher of Wisconsin experienced just before turning 10, when he watched his 37-year-old father die of a heart attack. Before that, his dad, who also was a smoker, had learned he had hardening of the arteries caused by high cholesterol.

Afterward, Korfmacher and his siblings had their cholesterol checked. He embarked on a lifetime of monitoring his diet, exercising and, later, taking medicine for high cholesterol.

Six years ago, when his own sons were 12 and 8, they were tested, too. Their cholesterol levels also were so high that doctors put them on small doses of statin medicine. Today, they are managing well.

“There’s no reason not to check it,” said Korfmacher, 55. “It’s one risk factor. Just because you have high cholesterol doesn’t mean you are going to die like my dad, but you should get plenty of exercise and not smoke. If you are overweight and staring at a screen, those things are just as important.”

Find more news from Scientific Sessions.

If you have questions or comments about this story, please email [email protected].