A little after 9 p.m. on a Friday in July, Dr. Kevin Volpp arrived at a restaurant in Cincinnati with his 15-year-old daughter Daphne, her squash coach and some friends. Everyone was tired and eager for a good meal.

Daphne was coming off her second long, intense match of the day, with another the next morning. The tournament was important enough to have lured them away from Philadelphia on the 52nd birthday of Marjorie Volpp, Daphne’s mom and Kevin’s wife.

Kevin needed to fuel up because he was 16 days from competing in an Ironman 70.3 event. He’d never done anything like it. But when one of his older daughters suggested it, doing something so challenging – and doing it with her – felt irresistible. By this night, he was easily in his best shape since his mid-20s.

Next to Kevin sat John White, the squash coach at Drexel University, boyfriend of Daphne’s coach and himself a squash legend. He’d even been nicknamed, “The Legend.” A former world No. 1, his game had been all about power. For years, he held the record for the hardest shot.

White ordered the filet mignon and Maine lobster tail. That sounded good to Kevin, so he ordered it, too.

Chewing his first bite, Kevin reached for his water but knocked it over.

Then he slumped onto the table and tumbled toward White.

His heart wasn’t beating.

***

What happened next is a story rich in lessons about living and about avoiding death. It’s about the importance of knowing CPR, why being fit always helps and what’s possible when every link in the chain of survival holds firm. Most of all, it’s about relationships, and how they can be forever changed.

On Monday, Kevin – a leader at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine and the Wharton School whose current research includes a variety of efforts to help people lower their risk of heart attacks – will share his story publicly for the first time at the American Heart Association’s Scientific Sessions, the organization’s flagship conference.

Put another way, thousands of people from around the world who are devoted to keeping hearts pumping will hear from one of their own about the day this summer when his heart stopped pumping.

“After the last year and a half, to say we need more wins is truly an understatement,” said Dr. David Harris, the attending physician in the cardiac care unit where Kevin was treated. “Kevin is an absolute win. He’s a patient I will always remember.”

***

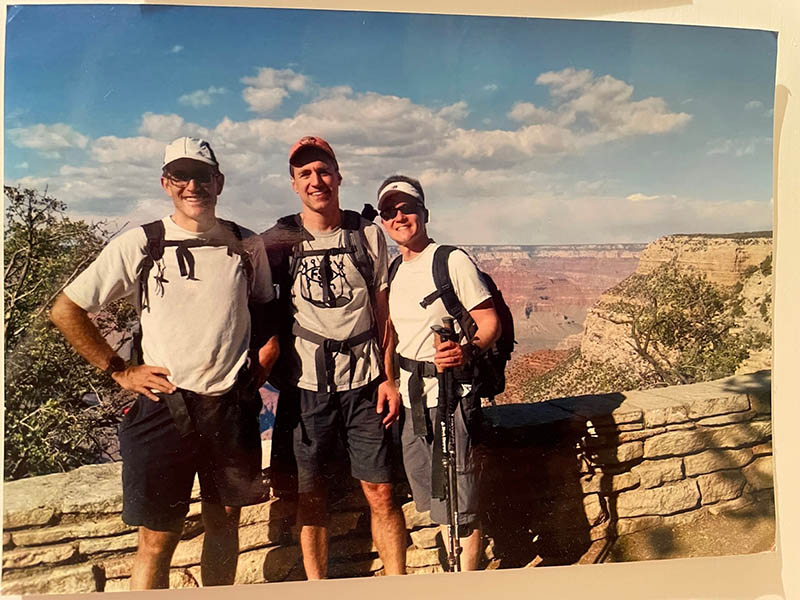

In a way, this story begins with a wild plan hatched in 2019.

Two college pals talked Kevin into preparing to join them for a run-hike from one rim of the Grand Canyon to the other … and back, a 47-mile journey with about 11,000 feet of elevation change known as the R2R2R.

A lifelong athlete, Kevin was nearly prepared for it. Then, two months before they had planned to set out, the COVID-19 pandemic hit.

The disappointment of canceling the trip was eased by how much time Kevin got to spend with his daughters. Daphne was finishing middle school and twins Anna and Thea were high school seniors.

In the fall of 2020, Anna went away to college. When she was required to take her next semester of classes remotely, she opted to instead take a gap semester and seek hands-on experiences such as getting certified as an EMT and working in medical clinics.

In February, she decided to enter the Ironman 70.3. The number comes from swimming 1.2 miles, cycling 56 and running 13.1. (It’s called a “Half Ironman” because the full event doubles each distance.)

Kevin had always wanted to enter an Ironman event. The time commitment to train for it was always an obstacle. Now it was an incentive to spend time with Anna.

***

On the advice of his Grand Canyon buddies, Kevin hired Juliet Hochman to train him and Anna.

Hochman is a former Olympic rower and a national age-group champion for the Ironman 70.3. Based in Oregon, she trains people across the country via online trackers and video chats.

Anna was an unusual client for Hochman; Ironman competitors are usually older. As a midlife high-achiever/weekend warrior, Kevin fit the profile. Working with the duo felt good to Hochman, the mother of two sons in their early 20s.

“If my kids asked me to do anything with them – skydiving, even – I wouldn’t hesitate,” she said.

Kevin ran, rode, swam or lifted weights each day. He competed in two Olympic-length triathlons (0.93-mile swim, 24.85-mile ride, 6.2-mile run). He was on pace to finish in under six hours.

Being so fit at 54 carried extra meaning for Kevin: His father had a heart attack at 55.

Gert Volpp’s heart attack happened while on a business trip to South Korea. By the time he was seen by his doctors, they said too much heart muscle had died and they couldn’t do anything about it.

“He went from a strong, vigorous man to not being able to walk up a half flight of stairs without having to stop,” Kevin said.

Another doctor suggested Gert contact Dr. Michael DeBakey, a pioneer of bypass surgery based in Houston. DeBakey performed a bypass on Gert and “within a couple of weeks, my dad was almost back to normal,” Kevin said. “It was like a miracle.” That was in 1985. Gert lived until 2019 without further heart problems.

Knowing his family history, Kevin went for a coronary calcium scan around the time he turned 50. The test showed a fair amount of buildup of plaque, the substance that causes a heart attack. Kevin began seeing a cardiologist and taking cholesterol-lowering medicine.

Yet as Kevin prepared for the Ironman, Gert’s saga and his own test results remained in the back of his mind. Something else made him ponder his mortality.

A few years ago, a close friend who was about the same age and in excellent physical condition died during an open-water swim race.

So before his first Olympic-distance triathlon, Kevin pulled out the thick folder where he keeps his will and Marjorie’s and other important paperwork. He put it on his desk so she could easily find it. Just in case.

***

On Thursday, July 8, Kevin rode 53.2 miles in Philadelphia, then flew with Daphne to Cincinnati.

The next morning, he ran 3.1 miles. It was supposed to be an easy run, but it felt hard. Then again, it was a hot, humid day.

He and Daphne went to the Cincinnati Country Club for her second tournament since the pandemic. A broken toe kept her out of earlier summer tournaments, so she needed this one to solidify her national ranking.

Her opening match went the distance, five games. A loss sent her into the consolation round – and an evening match. She won the first two games, then lost the next two, including a tiebreaker that stretched almost as long as another game. In the finale, she cruised to victory.

The match took so long that their group was late for their dinner reservation. Kevin and Daphne were to be joined by her friend Audrey Gelinas and her mom Jen, along with Gina Stoker, who coaches both girls, and Stoker’s boyfriend, White.

***

Now 36, Stoker had played professionally in her 20s. She played for England’s national team before moving to Philadelphia to coach.

She and White arrived in Cincinnati around 1 a.m. Friday, along with their four dogs. After the final match Friday, Stoker and White went to the hotel to check on the dogs. They considered staying in and joining the others for dinner the next night.

They probably would have if the restaurant hadn’t been across the parking lot.

***

When White and Stoker arrived, Daphne was sitting next to Kevin. She gave her seat to White and moved to the other side of the table.

Because of that, when Kevin collapsed and rolled left, White caught him.

White lifted Kevin by the shoulders and placed him back into his chair. His body felt stiff.

Stoker immediately pulled out her phone to call 911, but her battery was drained. So she used Daphne’s phone. Jen took Daphne and Audrey to another part of the restaurant to keep them from watching the events play out.

Waitstaff and fellow patrons looked on in horror, helpless. There was no doctor, no one else who knew CPR. The restaurant didn’t have an AED.

The restaurant manager thought Kevin was choking, so he tried giving him the Heimlich maneuver.

“Get away from him!” White screamed. He placed Kevin on the floor, rolled him on his side and checked his airway. Then White put Kevin on his back. He appeared to take a breath.

Confused, White checked for a pulse. There was none. He checked for breathing. There was none.

As coaches, White and Stoker are trained in CPR. They go through refresher courses every year or two. Stoker had even been part of two save attempts, both successful.

As former pro athletes, they’re accustomed to performing under pressure.

***

White started giving CPR. He kept going until police arrived and took over.

When paramedics arrived, they put a breathing mask on Kevin and – as White saw – he appeared to take a breath. But he still had no pulse.

They connected him to an AED, a portable electronic device that analyzes the heart rhythm and, if needed, can deliver a shock to try restoring a normal rhythm. The machine advised that a shock was needed. They deployed it, then gave more chest compressions.

Another check of the AED showed he needed another shock. The machine jolted him again.

Kevin’s pulse became strong enough to take him to the ambulance. When the doors closed, White and Stoker exhaled.

Until they realized the ambulance wasn’t leaving.

***

Kevin’s pulse had disappeared again, requiring a third shock.

Through the back glass, White and Stoker saw the paramedics providing CPR. Then the action slowed. A paramedic climbed out a side door and walked to White and Stoker.

Stoker’s chest and stomach tightened. She envisioned herself having to tell Daphne her dad didn’t make it.

“We lost him back there,” she recalls the paramedic saying, “but we finally stabilized him.”

***

Kevin collapsed because of cardiac arrest. Essentially, his heart’s electricity went out.

The cardiac arrest was caused by a heart attack. Consider that a plumbing problem: an artery in his heart was blocked.

En route, paramedics called the hospital with details. A team was waiting in the cardiac catheterization lab. Doctors found one of his arteries 99% blocked. They performed a minimally invasive procedure that involved inflating a balloon to open the narrowed pathway and inserting a stent to keep it open.

***

Meanwhile, in Philadelphia, Marjorie enjoyed a birthday dinner with family. Later, she and the twins were settling onto the sofa to watch a TV show when she noticed a missed call from Daphne. As she picked up the phone, Daphne was calling again.

“Hey Daph!” Marjorie said.

She heard Stoker’s voice.

“Is it Kevin or Daphne?” Marjorie thought.

“It’s Kevin,” Stoker said.

Marjorie busied herself with calls – travel plans, medical advice from friends, even arranging a three-way call with Kevin’s primary care clinician in Philadelphia and one of the emergency room doctors.

Awaiting news from the cath lab, Marjorie wanted to alert Kevin’s colleagues. She opened his computer to find their numbers. She didn’t know the password.

That’s when her resolve cracked.

As a clinical social worker, she’s accustomed to consoling others. Luckily, her brother – a psychiatrist visiting from California – and her mom were there to console her and the twins.

***

Thanks to Kevin’s extreme fitness, his body began recovering quickly. The unknown was his brain.

He’d gone without a pulse, thus starving his body of oxygen, for about 14 minutes. Permanent brain damage can begin within minutes.

Once he regained consciousness, Kevin was confused, as is typical.

Yet by Saturday night, he understood all that went wrong with his heart – and he began absorbing all that went right to fix it.

Harris explained that the key to his survival was immediately receiving high-quality CPR.

“How do you know I received high-quality CPR?” Kevin asked.

“Because I’m talking to you 25 hours after the event,” Harris said.

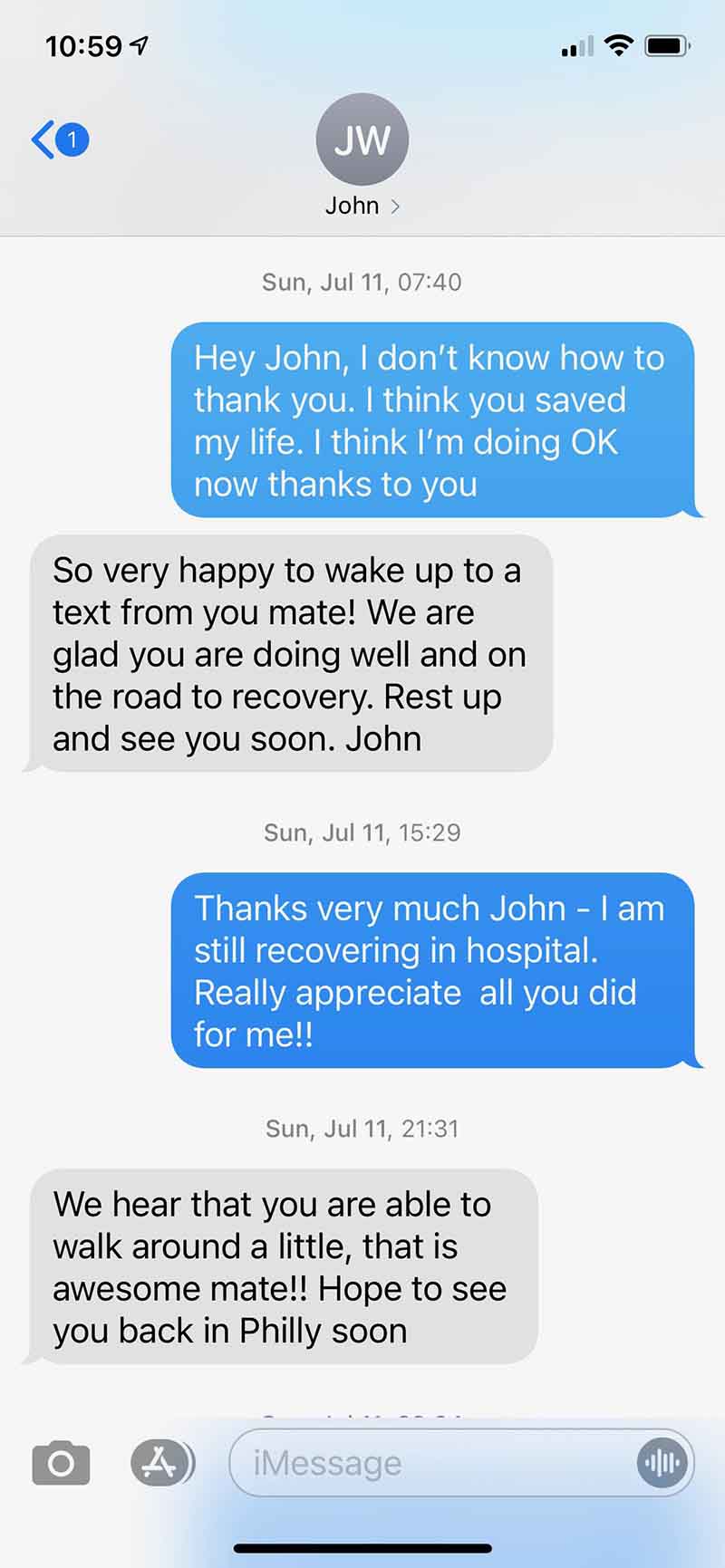

At 7:40 a.m. on Sunday, Kevin tapped out the following text to White: “Hey John, I don’t know how to thank you. I think you saved my life. I think I’m doing OK now thanks to you”

***

Kevin was incredibly fortunate to go into cardiac arrest in public, around folks trained in CPR and confident enough to use it. And that wasn’t all that fell into place perfectly.

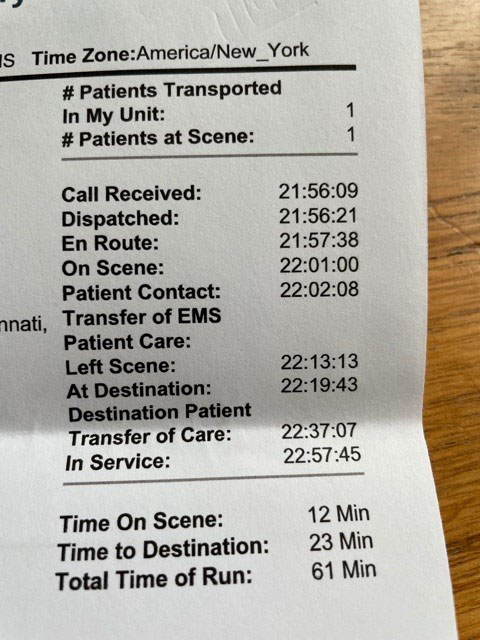

- 911 was called right away.

- White and then a police officer provided CPR continuously until paramedics took over.

- Paramedics arrived with an AED within five minutes of the 911 call.

- The ambulance left 12 minutes later and made it to the hospital in six minutes.

- From reaching the hospital until Kevin’s artery was open (what’s known as “door-to-balloon time”) took 1 hour, 8 minutes. The target is less than 1 hour, 30 minutes.

With each successful step, Kevin’s odds improved.

Still, survival rates for cardiac arrest outside of a hospital nationally are around 10%.

***

Kevin came away filled with joy and gratitude. Then came the unanswerable question: “What if?”

As in, what if any of the links in that chain had been weaker?

Would he have survived? Would he have fully recovered physically and cognitively?

Having spent about 20 years working in primary care and taking care of hospital inpatients, Kevin knows all too well how differently this could’ve played out.

What he could not have known was how this best-case result affected everyone connected to it.

***

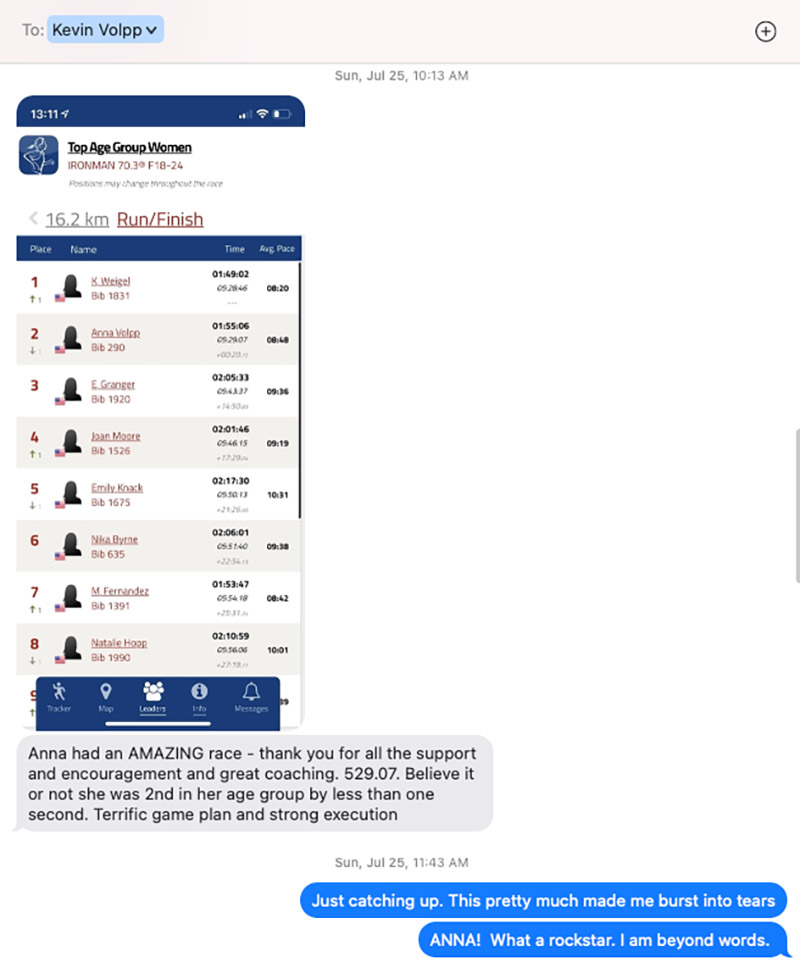

ANNA

With Kevin out of the Ironman 70.3, Marjorie was scared for Anna to compete in the race two weeks later. She told her so.

“Mom, I want to do it,” Anna replied. After all, competing was her idea.

Wearing Kevin’s white baseball hat, she finished second of 23 in her age group.

She qualified for the world championships in September. She opted to return to college.

***

THE COACH

Kevin texted a screenshot of Anna’s results to Hochman. She didn’t see it right away because she was competing in a 70.3 event herself that day in Oregon.

It was Hochman’s first 70.3 since beating cancer. She won her age group. Yet it was seeing how Anna did that “totally made my day,” she said, the thrill still evident in her voice months later.

The day after Kevin’s cardiac event, Anna had texted the news to Hochman. She immediately asked herself, “Is this something I should’ve seen? Is this something I could’ve prevented?” She reviewed each of his workouts for the last month. She found “no spikes in his heart rate or anything.”

“Kevin has communicated to me a number of times that his doctors say had he not been in such good shape, he probably wouldn’t have survived,” she said. “I guess that’s the whole lesson. If it truly can happen at any time, we should all want to be in the very best health possible.”

Hochman, by the way, competed in the world championships. She won her age group.

***

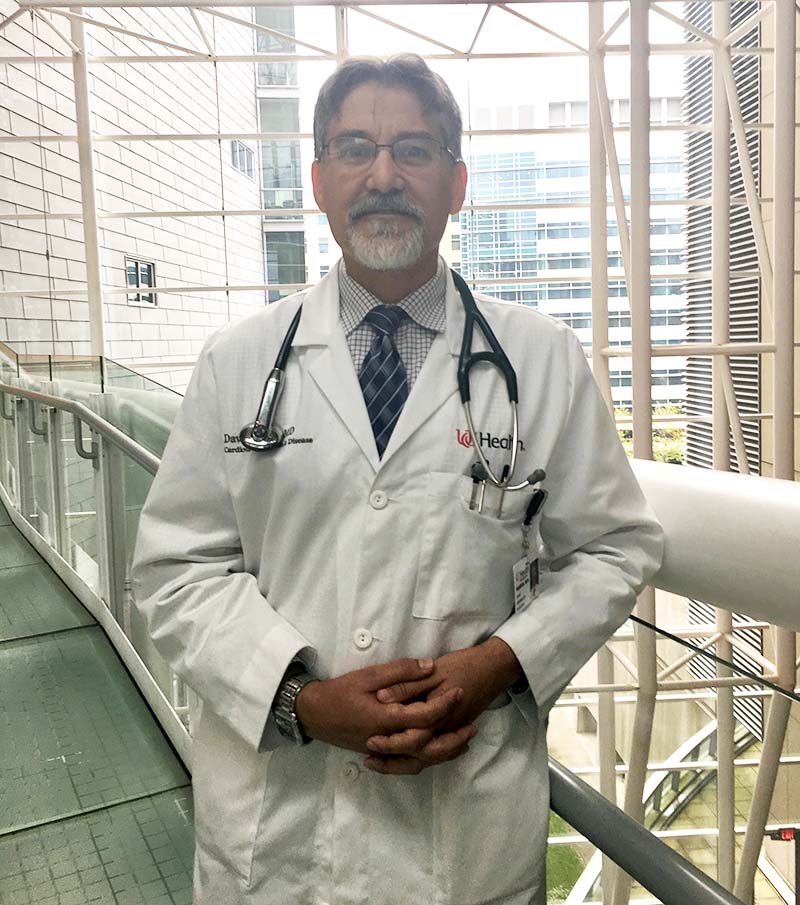

THE DOCTOR

Harris considered Kevin “a win” when he left the hospital with minimal issues.

Only later did Kevin elevate to “a patient I will always remember.”

“For him to be back to work and highly functional in three months – to be as healthy and active as he wants to be in his life – that is the miracle,” Harris said. “Everything we did worked.”

Harris emphasizes the word “we.” After all, the chain of survival is accomplished by people – far more than those spotlighted in this story. Other pivotal players Harris mentioned include people and teams from critical care anesthesiology, neurocritical care, electrophysiology, cardiac critical care nursing, cardiology fellows, internal medicine residents, echo sonographers, physical, occupational and speech therapists, social workers and care coordinators in Cincinnati, plus caregivers in Philadelphia.

“All of these people and groups help in Kevin’s survival, acute medical care and recovery,” Harris said.

Beyond the emotional lift, Kevin changed Harris’ life in a tangible way: He’s since bought a high-tech stationary bicycle. He rides it several times a week.

“Kevin was a wakeup call for me,” Harris told Marjorie.

***

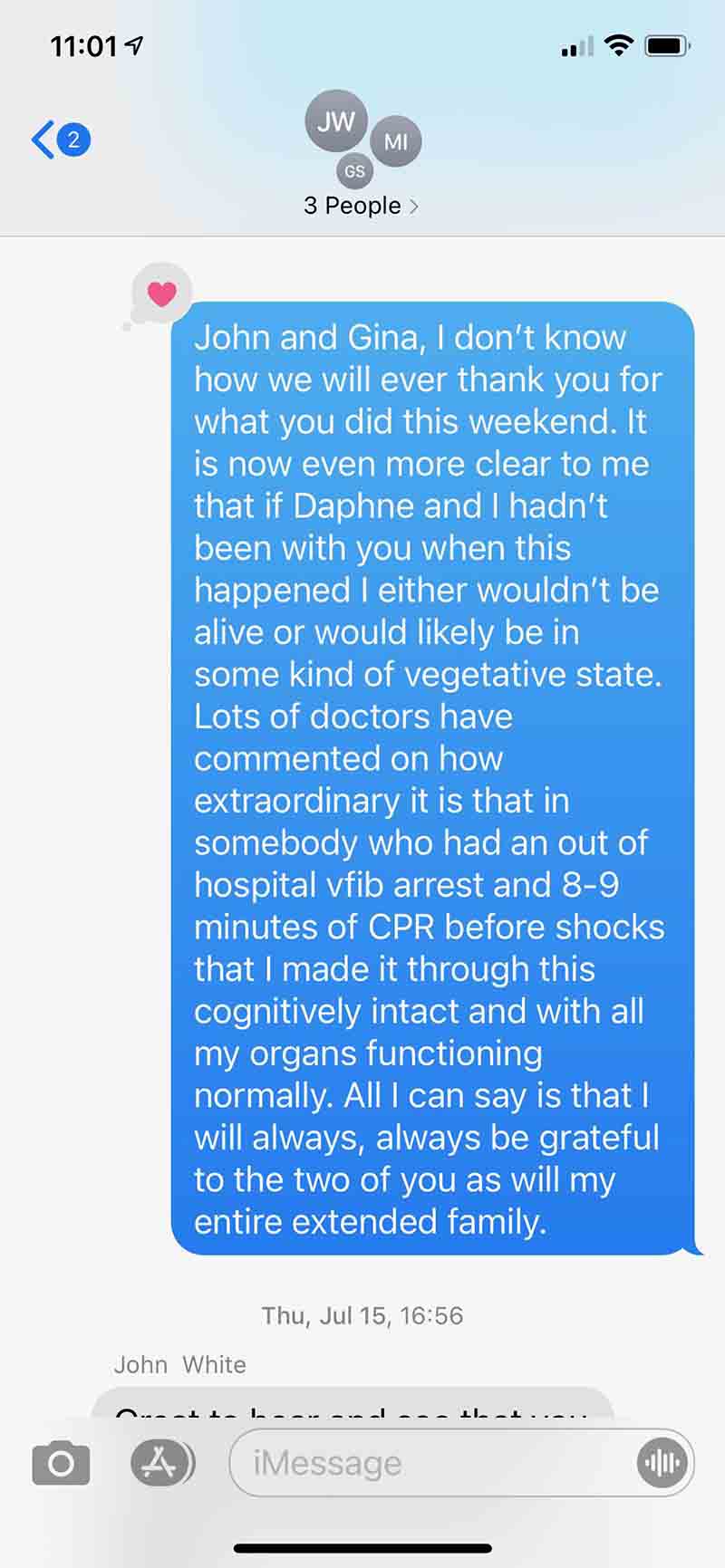

THE LIFESAVERS

While Kevin was in the cath lab, White brought Daphne to be with him, Stoker and the dogs at their hotel room. Then White slipped away to make a phone call. To Australia.

He needed to chat with his dad, who’s done CPR twice and could relate to what he was feeling and thinking.

As White started explaining what happened, he began crying.

“Just take a deep breath,” his dad said.

“What do I do now?” White asked.

“There’s not much else you can do,” his dad said. “I’m proud of you.”

The Sunday morning text from Kevin boosted White and Stoker. Hours later, they received another text – pictures of Kevin smiling.

The next day, back in Philadelphia, Stoker was getting ready to go to work when everything that happened in Cincinnati flooded her mind. Despite what was beginning to look like a rapid recovery, she felt gripped by uncertainty.

“Could we have done something differently?” she wondered. “I hope down the road he doesn’t have anything go wrong because of something we did.” She worried whether he would “still be Kevin.”

A few days later, Kevin texted them both to again express his gratitude. The phrasing showed he was definitely still Kevin.

Weeks later, Kevin conspired with Stoker for a surprise reunion with White at the squash club. White came around a corner and there was Kevin, outside the court where Stoker was working with Daphne.

The moment generated lots of tears, hugs and pictures. It also provided some closure for both men.

By that point, they had a running joke about John not eating his filet mignon and Maine lobster tail.

He has since at one of Philadelphia’s best steakhouses, courtesy of the Volpps.

***

DAPHNE

Before Daphne was whisked away from the scene of her dad’s collapse, she saw what White and the paramedics saw – Kevin appearing as if he was taking a breath.

That gave her hope: Maybe he was just choking.

“On some level, I knew it was serious – I just didn’t want to believe it,” she said. “I was pretty lost.”

So lost that she didn’t want to call home and ruin her mom’s birthday. Then her sister Thea called, crying, asking for details. She hardly had any, further swirling her emotions. At the hospital, caregivers asked Daphne her dad’s age and health history. She felt extreme pressure to get everything right.

When Marjorie arrived the next day, White and Stoker took her and Daphne to the hospital. Walking into the intensive care unit, seeing how stressed and worried her mom looked, hearing all the machines beep, “it finally felt real,” Daphne said.

Before they got to his room, a nurse assured them Kevin was doing well. Daphne was so overwhelmed that she opted not to see him right away.

“I didn’t want this image of my dad in the hospital, unconscious, if I knew I was going to see him again once he was better,” she said.

That night, Anna and Thea flew in, as did Kevin’s three sisters. At the hotel, one of Kevin’s sisters ran to White, hugged him and said, “You’re the man who saved my brother’s life!” Daphne had no idea. Neither he nor Stoker had mentioned it.

Over time, Daphne has gone from feeling guilty that this happened to her dad while on a trip with her to realizing how fortunate it is that things played out as they did. She shudders at the notion that Kevin could’ve collapsed in their room the night before – or, perhaps, at the exact same time, but had her match ended earlier, they might’ve been back in the room alone.

“I’m not sure I would’ve known what to do,” she said.

Soon, she hopes to.

A couple of weeks later, a friend who is an ER physician offered to come over to train the family in CPR. Even Anna, the recently certified EMT, took part. Daphne, however, wasn’t ready. The emotions associated with it were too raw.

“But I definitely want to learn,” she said, “because I realize how important it is.”

***

MARJORIE

When Marjorie learned that Kevin collapsed, her deepest fears rushed to the surface.

“I felt like I was living my life waiting for this to happen,” she later recalled.

In the months since, she’s often thought about how close she came to becoming a widow. Although she knows heart disease can’t be fully prevented, she had taken so much solace in how proactive he’d been, from his fitness to his diet to regularly seeing his cardiologist and taking daily medication.

“Despite that, why did this still happen?” she said.

Her ruminations always end with the most important detail: Kevin’s life was saved on July 9. And that means they now share that date. Her birthday is his rebirth-day, as many cardiac arrest survivors call it.

“When something like this happens, it really makes you focus on what’s important. You give yourself permission to let go of all the unnecessary stuff that causes you stress,” she said. “And so it is a rebirth of sorts – for him, for us as a couple and for us as a family. We’re really trying to do things in a more intentional, meaningful way.”

***

KEVIN

For a few weeks after his life was saved, Kevin’s chest and ribs were sore.

“But it was sort of a pleasant reminder of how people helped me survive,” he said. “So I didn’t mind.”

He traded Ironman training for cardiac rehabilitation. Instead of running a mile in about 8 minutes, 30 seconds, he walked a half-mile in roughly that time.

Upon graduating rehab, a stress test showed no problems with the stented artery or with the rest of his heart. He exercises up to an hour a day at a level appropriate for someone a few months out from a heart attack.

He’s also rejoined Hochman’s triathlon club.

That hints at the balance Kevin is trying to negotiate: moving forward while bungee-cord-connected to his recent past.

“I’m choosing to believe the narrative that all these things perfectly fell into place to save my life for a reason,” he said. “There’s a lot for me to yet do in this world.”

Such as helping fewer people die of heart disease, thus giving more people more time with their loved ones.

Kevin is one of two leaders of a five-year grant from the National Institutes of Health to study how behavioral economic approaches (think, “nudges”) can increase physical activity among patients at higher risk of heart disease. He is also leading a multi-project initiative at Penn Medicine on reducing heart attack risk by influencing patient and clinician behavior and has published more than 150 articles on related topics.

“It’s always been one of my most important efforts,” he said, “but now I’m doubling down on it.”

Stories From the Heart chronicles the inspiring journeys of heart disease and stroke survivors, caregivers and advocates.

If you have questions or comments about this story, please email editor@heart.org.