Fresh out of college with a degree in nutrition, Olivia Hart went home to Martha’s Vineyard to waitress and figure out her next steps. In her spare time, she rode horses, a lifelong passion Olivia shared with her fraternal twin sister, Sofia.

Long hours on her feet left Olivia exhausted. She couldn’t catch her breath, her heartbeat was erratic. It felt like blood was draining in her arms and legs. Olivia was training for a half-marathon, too. Despite the increased exercise, she gained 15 pounds. Her skin was also tinged gray.

Olivia went to urgent care. The doctor told her it was gastroesophageal reflux disease, a chronic case of stomach acid rising into the esophagus. Olivia was unconvinced. She’d never had digestive problems before.

Two weeks later, halfway through a 12-hour work shift, her boss sent her home to rest. She ended up at a Boston hospital, her heart beating 135 times per minute. (A normal resting heart rate for most adults is between 60 and 100 beats per minute.) Tests showed her heart was enlarged.

She then went into cardiogenic shock. Her heart rate was dropping and the medical team couldn’t get a blood pressure reading.

They were able to stabilize her, and the next day her doctor delivered the news: She had heart failure and they weren’t sure why.

Relieved to at least have a diagnosis, Olivia asked, “So how do I feel better?”

“You need a heart transplant,” the doctor said.

Five days later, she had a left ventricular assist device, or LVAD, implanted in her chest. The battery-controlled device essentially pumps blood instead of the diseased part of her heart. It’s often used as a “bridge to transplant,” but also can be a long-term solution.

A year and a month later, Olivia got the call. Doctors prepped her for surgery. But when she woke from anesthesia, there was no incision. It turned out that the donor heart wasn’t as good of a match as initially thought.

She was on the ferry home to Martha’s Vineyard when her phone rang. “Come back,” doctors said. There was another heart. She flew to Boston and had a successful heart transplant hours later at age 22.

The following months were challenging. She was in and out of the hospital. Her body started to reject her new heart. Medication helped.

Olivia also felt down. She thought about her donor, a woman who had overdosed on drugs. “It was an all-encompassing feeling of survivor’s guilt,” Olivia said. “I struggled a lot with, why did I survive?”

While in the hospital, Olivia had a revelation. She found the next step she’d been seeking.

“I want to go into medicine,” she told her mother, Salli, who was by her bedside.

Three months and a day later, Olivia started working as a medical scribe, then an emergency medical technician, medical assistant and medical technician at her local hospital.

Around seven years later, Sofia worked on a horse farm near her home. As the sole employee taking care of 13 horses, it somewhat made sense that she was exhausted, achy and breathless.

Considering how much time she spent outside and in the woods, she thought she had Lyme disease.

Yet she noticed something else weird: Despite being more active than ever, she was gaining weight.

One day at work, Sofia blanketed and turned out the horses and scrubbed water buckets, then felt weak and out of breath. She ended up in the emergency room of the hospital where Olivia worked. Sofia let her sister know she was there.

Sofia told doctors she thought she had Lyme disease. Tests on her heart’s electrical activity and structure showed otherwise.

Doctors let Olivia share the news. She told Sofia: “So, you’re going to Boston. You’re in advanced heart failure.”

The next day, Sofia was airlifted to the same Boston hospital where Olivia was treated. She went to the cardiac intensive care unit. The same doctor that performed Olivia’s heart transplant told Sofia she needed one, too.

Sofia started a heart failure medication. Maybe that could stabilize her, doctors hoped, and she wouldn’t need an LVAD before transplant.

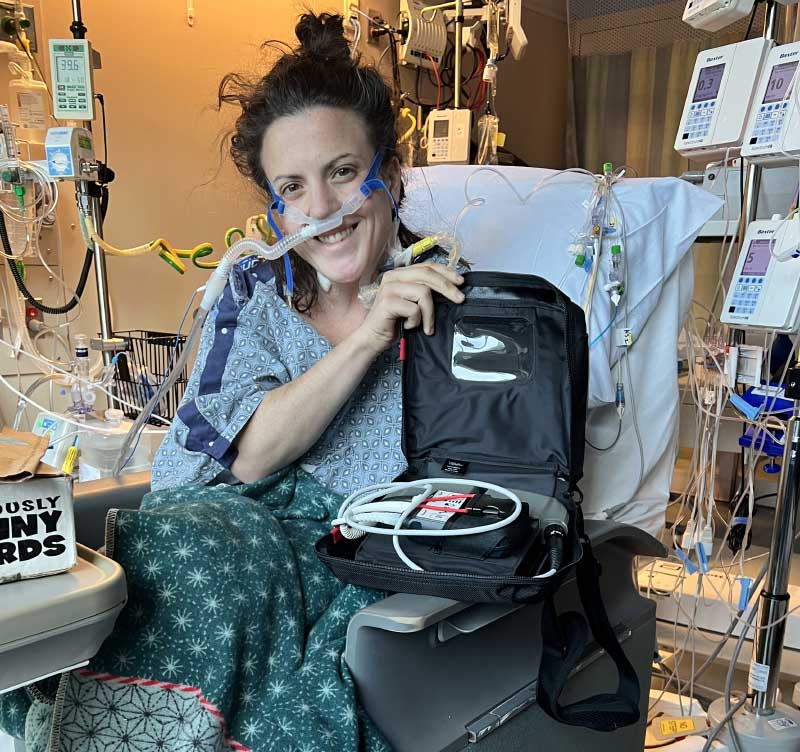

But Sofia’s health deteriorated. In late 2022, she underwent an emergency procedure to implant an LVAD.

Scary as it was, it helped knowing she’d have the support of Olivia – both her twin sister and someone who’d lived with the device.

More than a year later, Sofia continues to have her heart powered by the LVAD.

“The LVAD and I are getting along really well,” she said.

She nicknamed it “Janis Joplin 2.0” after her favorite singer.

After Olivia’s ordeal, no one considered genetic testing.

After Sofia’s ordeal, it only made sense.

Indeed, tests showed they have a rare genetic mutation that caused their hearts to enlarge and then deteriorate. Their condition is called irreversible dilated cardiomyopathy, or DCM; it happens when the heart chambers enlarge and can’t properly pump blood.

Finally, Olivia knew the cause of her own heart failure years earlier. It turns out that their mother has the defect, too, but never got sick. Their younger sister, Julia, doesn’t have the gene and their brother, Jake, hasn’t been tested.

Sofia is not on the transplant list. She wants to first get her finances in order and to prepare physically and mentally. Learning from Olivia’s experience, she realizes that “my donor is living today, and the day I go in for transplant I know the person’s life ended that day.”

In the meantime, she’s channeling her feelings online, sharing her story on social media. Her best friend encouraged her to post videos about her health journey.

“I did that video for myself,” Sofia said. “But when you help yourself, it can really help so many others, too.”

Her first video went viral, chalking up nearly 100,000 views. Sofia now has 40,000 followers on TikTok. She documents life with an LVAD and what it’s like to be a heart patient, connecting with young people worldwide going through similar experiences.

“It’s hard to not feel isolated and alone going through this,” she said. “Leaning into social media has really helped me.”

Her experience has given her direction, too. Like her sister, she wants to work in health care and advocate for patients. “In my 20s, I didn’t have a path,” she said. “My entire soul shifted in that med flight. I knew my life’s purpose.”

Sofia lives in Boston and continues to speak about the need for more heart research and the patient experience. One day she hopes to have her own health nonprofit and raise funds to help heart patients.

Olivia, for her part, has learned how to advocate for herself. “This whole process has been a curse and a blessing, but more so a blessing now. There’s no place I’m more myself than when I’m practicing medicine.” She works as a paramedic in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

“Sofia and I now share the same goal,” she said. “We both want to help people understand that they’re not alone, that there are resources for them.”

Stories From the Heart chronicles the inspiring journeys of heart disease and stroke survivors, caregivers and advocates.