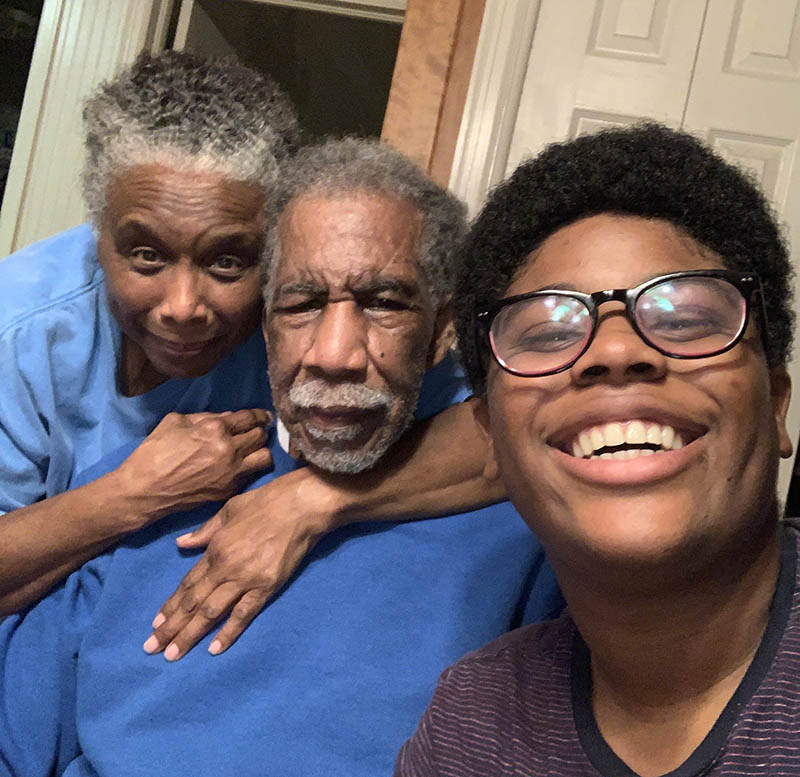

When then-college student Lumiere Rostick learned their grandfather, who had dementia, needed help, Rostick volunteered to move in with him.

Rostick, whose pronouns are they/them/their, worked on remote college classes and in between helped their grandmother clean and cook, as well as feed, dress and change their grandfather – just some of the many responsibilities.

Rostick was not alone. In fact, millions of caregivers are not yet high school graduates.

According to a National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP survey, there are at least 3.4 million caregivers under the age of 18 nationwide.

Those numbers are likely an underestimate, said Connie Siskowski, a nurse and researcher who founded the American Association of Caregiving Youth (AACY), a Florida-based nonprofit that supports youth caregivers.

In fact, AACY says in Florida alone, nearly 300,000 middle school and high school students provide caregiving of some sort.

“Caregiving youth are not on people’s radar,” Siskowski said. “What they do is behind closed doors, so it’s out of sight, out of mind.”

She said the opioid crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic have led to a greater number of single-parent and single-grandparent households, which can “push caregiving down to the children.”

Even for families who have the means to hire additional help, being a young caregiver can take a toll, Siskowski said, and the added stress can negatively impact health, resulting in headaches, stomach problems and an inability to focus on school.

“When you’re in a period of extreme stress, it’s almost impossible to learn,” she said. “They have more anxiety and depression than their counterparts who are not caregivers.”

In fact, a study funded by The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation found 22% of young adults who dropped out of school did so to care for a family member.

Determined to ease the burden of youth caregivers in Palm Beach County, AACY provides a six-week skills building course from sixth grade through high school, along with home visits, recreational activities, tutoring, mentoring and other services.

“It depends on their needs,” Siskowski said. “It’s a holistic approach. We try to provide respite that is youth-directed. It may mean a home health aide, delivered family meals or even home cleaning.”

More work is needed, Siskowski said, to identify and provide support for young caregivers, both emotionally and financially. She believes providing such support would offer an immediate return on investment.

Indeed, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported high school graduates earn more than $8,000 more per year on average than those who do not have a degree.

Unlike many young caregivers, Rostick’s grandparents, Georgia and Bobby Philpot, had the resources to bring in additional help when needed. Nearby family members also provided support. In addition, Georgia is a retired nurse.

“It wasn’t all on me, but it still felt heavy,” said Rostick, who was 22 when they moved in with their grandparents in Griffin, Georgia, for eight months until their grandfather’s death in 2020.

“There were moments that were hard, but it was a really beautiful time for me to bond with him when I hadn’t really had that time before,” they said. “It was my choice, and it was a choice that I’m happy with.”

With the proper support, Siskowski believes caregiving can positively impact a young person’s life, providing a sense of purpose and helping them to develop better time management, empathy and other life skills.

“These are amazing young people,” she said. “Supporting them is really valuable all the way around, for both the children, their families and society.”

If you have questions or comments about this story, please email editor@heart.org.