Between her nausea, chills and profuse sweating, Liz Johnson thought she was coming down with the flu.

The seventh-grade math teacher struggled through the rest of her 90-minute teaching block before heading to her home in North Lima, Ohio.

Her husband, Steve, was traveling for business, so Liz – then 39 – stopped at an urgent care clinic hoping to get some medication before going home. Doctors did an electrocardiogram to measure the electrical activity of her heartbeat. When the test came back abnormal, she was advised to go to a hospital emergency room for more tests.

“I’m just stressed out,” she told them. “My husband travels and I’ve got three kids.”

Liz was admitted to the hospital overnight, with a cardiac catheterization procedure scheduled for the next day. She figured doctors were just being extremely cautious.

The test showed a total blockage of one of her main coronary arteries. She was having a heart attack.

“It was hard to even grasp what had happened,” Steve said. “She had had a heart attack and we had no idea why.”

Liz never had high blood pressure or high cholesterol and didn’t have a family history of heart disease. She ate a heart-healthy diet and exercised regularly.

“I never thought healthy people could have a heart attack,” she said.

A cardiologist later diagnosed Liz as having had a spontaneous coronary artery dissection, or SCAD. Blood accumulated between the layers of the artery wall, causing it to bulge and block blood flow.

In Liz’s case, the blockage was severe enough to cause a heart attack, with symptoms that can range from chest pain to a cardiac arrest. For people with SCAD who have a partial blockage, symptoms can include shortness of breath, a rapid heartbeat, sweating, nausea and fatigue.

SCAD is rare and can occur at any age, but those who experience it are most often women who are otherwise healthy and between age 30 and 50.

Liz was referred to specialists at a Cleveland hospital about an hour away. Additional testing failed to confirm what caused the SCAD. She was treated with medication to reduce her risk for future heart attacks and told to avoid extreme exertion, lifting anything over 35 pounds and riding roller coasters.

Her doctor told her there was a 10% chance of another SCAD within a year. If it didn’t happen, she faced only a 1% chance of recurrence.

“Once I hit the one-year mark, I was ecstatic,” she said.

But in October 2017, 18 months after her first SCAD, Liz woke up in the middle of the night with a tightness in her chest. Still feeling uncomfortable that morning, she drove herself to the hospital to get it checked out while her husband took the kids to church.

“I was joking with the nurses that I had a wine tasting party to go to later,” she said. “I felt fine otherwise, it was just a little bit of chest tightness.”

Tests showed she was having another heart attack.

Liz was sent by ambulance to the same hospital in Cleveland. A catherization procedure didn’t show any blockages, but while the doctor was out of the room to update Steve, Liz suddenly felt an excruciating pain.

“It was a level 10 pain,” she said. “I thought I was going to die.”

Liz was having another SCAD. This time, a team of specialists consulted on what to do. Another stent was too risky. So was bypass surgery, based on the location of the tear. Ultimately, they used a balloon pump to reopen the blockage and allow her artery to heal. She spent two weeks in intensive care.

“After the second time, we realized nothing is ever going back to normal,” Steve said. “This is going to be a chronic condition that will have to be managed for the rest of her life.”

Fifteen months later, the toll of the second SCAD became clearer.

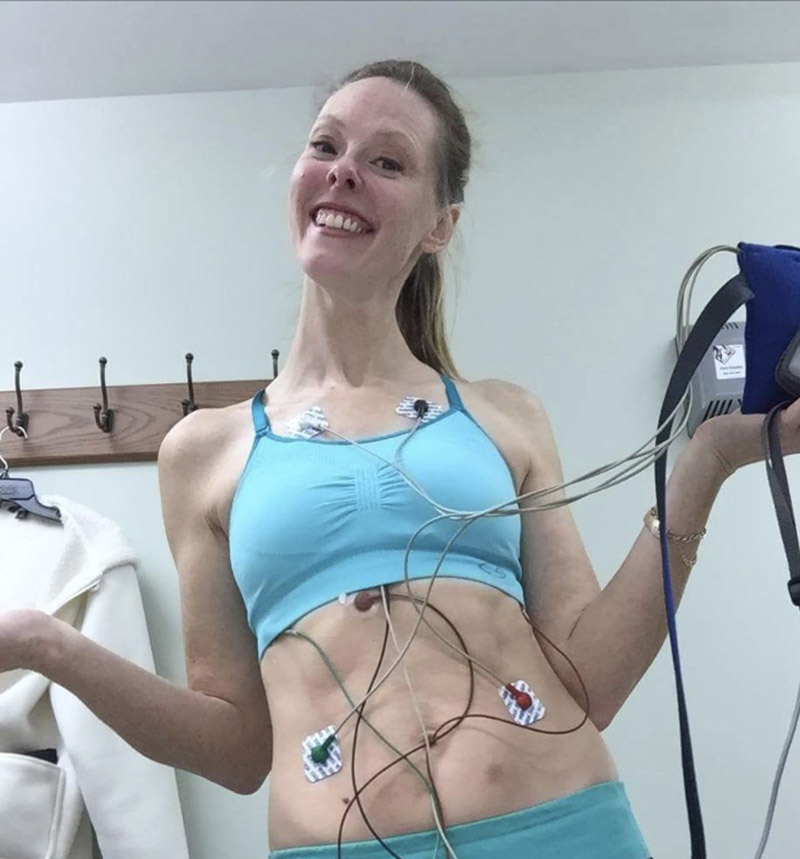

Damage from the second heart attack caused systolic heart failure. Her left ventricle is unable to contract normally, limiting her heart’s ability to pump efficiently. Doctors were concerned about her risk of cardiac arrest, so they placed an implantable cardioverter defibrillator to restore a healthy rhythm if needed.

“It’s my smoke detector with a sprinkler system,” she said, laughing.

Last year, she began a new formula of medications to reduce strain on her heart. They’ve worked so well that her heart, which had enlarged, is back to its regular size and with improved efficiency.

She’s also retired from teaching to take care of her kids – and herself – full-time.

In the years since her first SCAD, she’s undergone therapy to help her process post-traumatic stress and has focused on gratitude.

“Mentally, I’ve always been a pretty positive person,” she said, “but now, as cliché as it sounds, I appreciate everything even more.”

She’s also more willing to take any health concerns to her doctor.

“As a mom, you think, ‘I’m too busy for this, it’ll go away,'” she said. “If there’s that little person on your shoulder saying, ‘Something is wrong,’ go to the ER and get checked. It could save your life.”

Stories From the Heart chronicles the inspiring journeys of heart disease and stroke survivors, caregivers and advocates.

If you have questions or comments about this story, please email editor@heart.org.