Murphy Jensen looked across the tennis court and smiled – a joyful, mischievous grin.

At 6-foot-5, with a smooth face and scalp, the bright flash of his teeth radiated warmth and happiness. Of course it did. This is a guy so peppy that a friend insists “the sun decides where to shine based on where Murphy goes.”

On this day, the eve of his 53rd birthday, he was playing a mixed doubles exhibition match against his big brother, Luke. It was at the Colorado resort where Luke was finishing his first week as director of racquet sports.

As doubles partners, the Jensen brothers once electrified tennis. It wasn’t just that they won the 1993 French Open, it was the way they did it. With long blonde hair, loud clothes and flying chest bump celebrations, they became the next big thing. The trajectory of their fame was more like a boy band with its first hit song than what they really were: up-and-comers in a niche part of a country club sport.

All these years later, they still draw a crowd. And Murphy still hits the ball wickedly hard. So even though this was a friendly competition, it was a competition nonetheless. That explains the sly part of Murphy’s smile, especially as he loaded up to serve.

Luke focused on Murphy’s eyes, gauging where Murphy was aiming.

Instead, Luke saw the strangest thing.

Murphy tossed the ball in the air, then closed his eyes.

The ball dropped and Murphy remained frozen in his pre-serve pose, eyes still shut.

Then he toppled backward. He went down like a tree, the back of his head slamming into the hard court. He was in cardiac arrest. His heart had stopped.

What happened next – no, actually, what happened starting the moment Murphy stood frozen a beat too long – launched a tale with many layers.

On the surface, it’s about the importance of knowing CPR and how to use an automated external defibrillator, or AED.

The deeper story, though, is about overcoming.

Murphy has turned away death several times. He’s walked the twisting path from addiction to long-term recovery. He’s faced mental health issues. Now he’s dealing with challenges sparked by his latest near-death experience, an episode that also left him with a traumatic brain injury and severe hearing loss.

Despite all he’s been through, his wife, Kate, describes him this way: “He still views the world through the eyes of a 6-year-old who doesn’t even know that life can be bad. It’s the magic of Murphy.”

That explains how he’s collected friends ranging from Bill Gates to Robert Downey Jr. It’s why he’s hung out with royalty and heads of state, hosted a TV show and co-founded a tech company. Perhaps the best example of Murphy magic is that he began promoting CPR and AED training nine years before those things saved his life on Oct. 29, 2021.

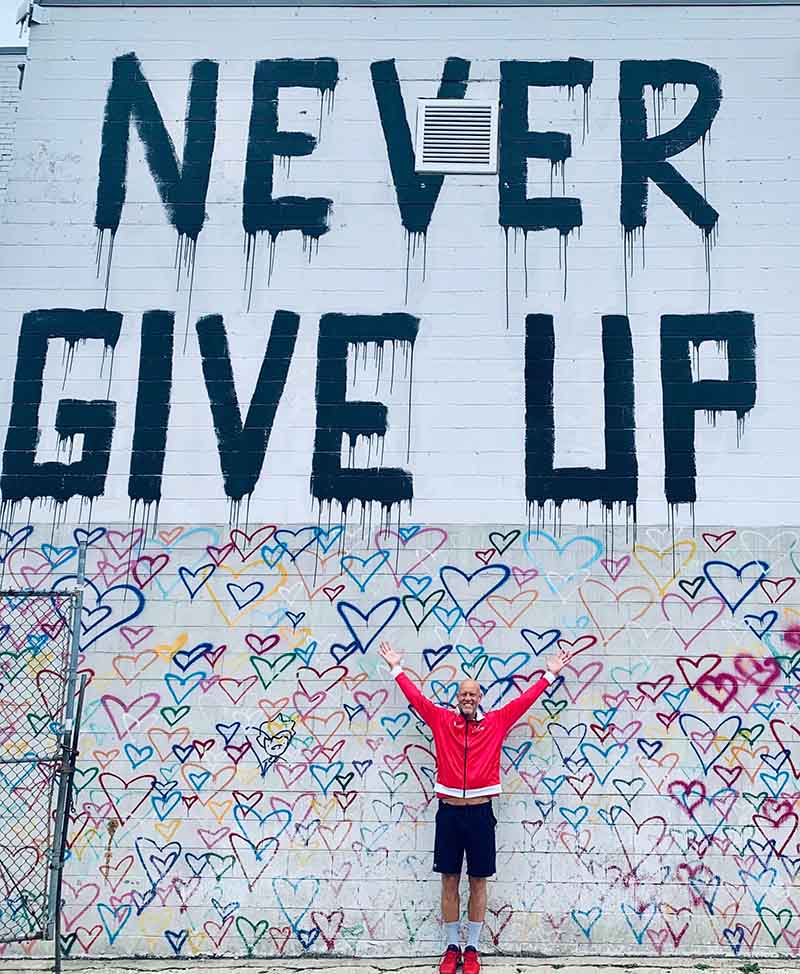

In celebration of his first “re-birthday,” as cardiac arrest survivors call it, Murphy is sharing his story for a simple reason. He believes it can help.

Help save lives by inspiring people to learn CPR and how to use an AED.

Help save lives by encouraging and destigmatizing addiction recovery and mental health therapy.

And, most of all, help save lives by offering hope.

Even though Murphy is a one-of-a-kind guy with a one-of-a-kind tale, his saga is rooted in something universal: Everyone is dealing with something. Unless it’s as visible as a bloody knee or broken arm, we probably have no idea what anyone else is going through.

“It’s about one word, man: L-O-V-E,” he said. “Love is the answer to all things. Love is everything, period.”

***

Seeing Murphy tip over in a cartoon-like way, Luke wondered, “Is this a prank?”

Then he heard Murphy’s head smack into the ground.

Two people with medical training were already rushing toward the court; they’d leaped from their seats the moment they saw Murphy’s eyes close. Two more trained lifesavers quickly joined them.

Someone shouted for an AED. Luke was sprinting toward Murphy when he heard that. So he turned and sprinted back to his side of the court, rushing to the wall. The day before, he’d been shown that’s where they kept an AED.

Kate was on an adjacent court, entertaining their son Duke, who was a few days shy of turning 4. She heard someone scream, “He’s down!” Through the maze of people between her and the prone body, she saw enough to know it was Murphy. She peeled Duke off her lap and ran. When she touched Murphy, his skin felt cold and looked blue.

***

About 200 people had come to watch athletes put on a show. Now they were watching bystanders who happened to be medical professionals performing as a team for the highest stakes.

A nurse gave chest compressions. An ear, nose and throat doctor gave rescue breaths. A retired fire chief controlled the AED. Another nurse assisted.

Luke’s role was keeping Murphy’s mind engaged. Standing near Murphy’s head, Luke shouted:

“DUKE NEEDS YOU! BILLY NEEDS YOU! KATE NEEDS YOU! I NEED YOU!”

“THIS IS NOT YOUR TIME!”

And the line he said most, their family motto: “JENSENS NEVER QUIT!”

***

THE GLORY DAYS

Luke and Murphy grew up in the small town of Ludington, Michigan, along with younger twin sisters. Their parents were school gym teachers. The family gravitated to tennis because they could play it together.

Luke loved the sport and excelled at it. Two years younger, Murphy excelled, too. Blessed with a long, lean body, he learned to leverage his size to hit a devastating serve.

Although he rose to No. 1 in the junior rankings, Murphy’s favorite part about tennis was being around Luke.

“He was my superhero,” Murphy said. “I just wanted to make him happy.”

***

When Murphy and Luke were young, their dad battled with alcoholism. He later found long-term recovery. But when Luke was a kid, he saw his dad drunk often enough to swear off alcohol and drugs. Besides, tennis meant everything to Luke.

He starred at the University of Southern California for two years, then turned pro. Murphy followed him to USC.

Unlike Luke, Murphy embraced all the temptations offered at fraternity parties.

In 1993, Luke was established on the tour and Murphy joined him on the top level. They eagerly became doubles partners, although with little success. Things were so bad that Murphy suggested Luke find another partner for the French Open. Luke refused. They arrived in Paris unseeded. They won six straight matches, forever sealing them as Grand Slam champions.

They happened to break through soon after John McEnroe and Jimmy Connors retired. Men’s tennis needed some pizzazz. The Jensen Brothers – all three words capitalized – provided plenty.

They partied at the Playboy Mansion and were profiled in People and Rolling Stone magazines. A poster of them oozed attitude, particularly Murphy with his feet up near the handlebars of a motorcycle, strumming an electric guitar. It fit their new label of playing “rock ‘n roll tennis.” They stoked that aura by wearing football and soccer jerseys during matches.

“We didn’t have to dare to be different – we were different,” Murphy said.

At the 1994 U.S. Open, tournament organizers put their third-round match on the biggest court and CBS showed it in prime time, two things unheard of for men’s doubles, before and since.

The fame, fortune and fun obscured something important. Tennis was still Luke’s thing, not Murphy’s.

***

In the locker room following their French Open triumph, Murphy’s body shook uncontrollably.

He was having a panic attack.

He feared that people would find out he didn’t deserve to be a Grand Slam champion. That he wasn’t worthy. That if people knew the truth, they’d never love him. He didn’t love himself.

That’s how Murphy explains it now. In the moment, and for years after, “I didn’t know what was wrong with me.”

Being celebrated as a winner while thinking he was a fraud created a gap between perception and reality. The more popular he became, the wider the gap.

Murphy filled it with drugs and alcohol.

***

At first, Murphy binged occasionally, mostly during his off-season.

Eventually, in-season, too.

Then the binges became more frequent. And more devastating.

The first time he tried rehab, he bailed out.

A few years later – on the same night his then-girlfriend, actress Robin Givens, gave birth to their son, Billy – a hotel manager in Los Angeles found Murphy in bad shape. He called someone who specializes in interventions. That guy told Murphy that he was within hours of dying from this lifestyle. This time, Murphy finished a treatment program, plus some aftercare.

Still, a cycle of binging to sobriety and back followed. It can be plotted against his tour ranking.

From a peak of No. 17 in 1993, Murphy plummeted to 1,240 in 1999. He clawed back to 280 in 2000, only to be in the 700s a year later.

Murphy found himself living in an RV or couch surfing. His woes impacted Luke’s career and caused problems with their mom; she’d become manager to all four of her kids, as the Jensens had become the first family with four siblings on the tennis tour.

In 2004, Murphy settled into a solid stretch of sobriety, aided by a new girlfriend. Then they broke up. And he relapsed again.

“I didn’t just disappoint those around me,” he said. “I disappointed myself.”

***

On June 1, 2006, while in Paris for the French Open, Murphy received an email from a life coach. It asked, “Do you want to have the best summer of your life?” and included a questionnaire.

Over croissants and cappuccino, he put pen to paper answering the questions.

Maybe it was writing it out. Maybe it was being in Paris, where his greatest professional feat unleashed his internal turmoil. Something about it sparked a moment of clarity.

Murphy finally understood some hard truths: “All the things I love and care about most I’ve hurt through drugs and alcohol.” And, “I need help I’m incapable of giving myself.”

He called his recovery sponsor and “began the process of unpackaging the baggage that was going to lead me to another drink.”

Murphy surrendered. He walked away from a life of alcohol and drugs; recovery, he vowed, was now his thing.

With that, he filled the hole in his soul.

By then, however, another demon was lurking inside him.

***

A BIG GUY WITH A BIG HEART

In 2003, sober and living in Santa Monica, California, Murphy went running along the beach. He must’ve fainted because the next thing he remembers is lying in the sand.

Weeks later, his consciousness flickered while playing tennis. He remained upright but it scared him enough to go see Dr. Norman Lepor, a cardiologist.

Lepor ran some tests, then told Murphy: “You’ve got a big heart. Massively huge.”

“I know,” Murphy said, smiling. “Thank you.”

“In terms of heart function, that’s bad,” Lepor said. “This is really serious.”

Months before, Murphy caught a virus. Apparently, that virus infected his heart and activated his body’s immune system. He’d developed myocarditis, causing an enlarged heart, a condition known as viral cardiomyopathy.

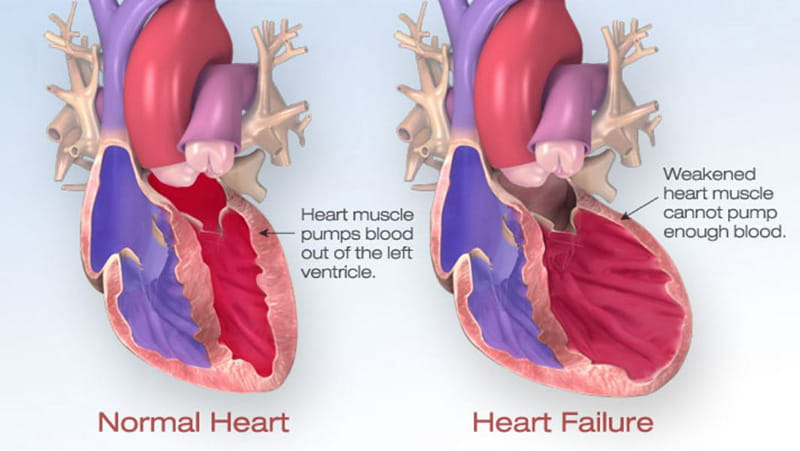

When a heart gets too big, it can’t efficiently pump blood to the rest of the body.

How much blood is pumped is measured by a metric called ejection fraction. Normal range is at least 50%; anything below 40% can be considered heart failure. Murphy’s ejection fraction was below 10%, a potentially fatal range. He also was in cardiogenic shock, another life-threatening condition.

As a 34-year-old athlete, Murphy responded well to treatment. Weakened heart muscle can become strong again, and his ejection fraction eventually returned to the healthy range.

Although he resumed a normal life, Murphy carried hidden, lingering damage from the myocarditis – microscopic scars within his heart muscle and potentially the electrical system.

***

Soon after, Murphy was among the first hires on the Tennis Channel.

He dazzled so much as co-host of “Open Access,” a show looking at players’ lives off the court, that he got his own show. “Murphy’s Guide” featured him touring his favorite cities.

Life flourished off-camera, too. He’d started dating Kate.

“I was really discovering who I am and why I’m here,” he said. “For the first time, I was a human being, not a human doing.”

So he wondered: Why is my heart beating upward of 200 times a minute?

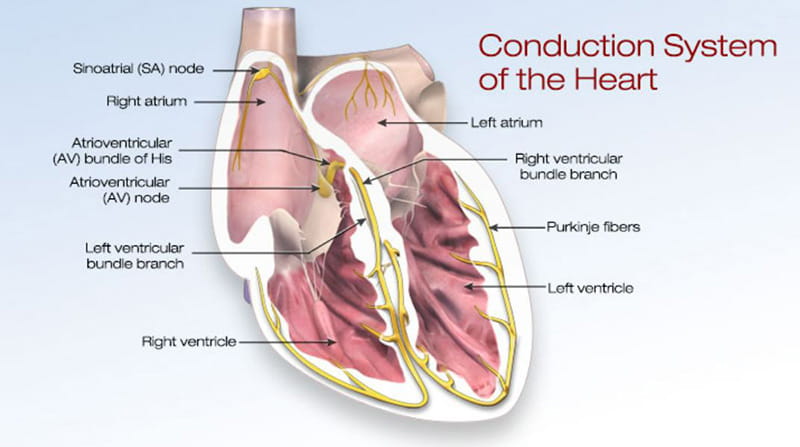

The reason was recurrent atrial fibrillation, or AFib, an irregular heart rhythm that can be caused by a glitch in the heart’s electrical system.

A non-invasive procedure called cardioversion restored a regular rhythm. It worked, but not for long, which is somewhat common in AFib. Once someone has it, they’re susceptible to having it again.

Murphy had more than a dozen cardioversions before undergoing his first ablation, a minimally invasive procedure that burned away the troublemaking spots on his heart.

***

Murphy enjoyed a normal heartbeat for several years. Then, in 2016, the AFib returned, along with a related problem, atrial flutter.

Now married and living near Seattle, he saw electrophysiologist Dr. Melissa Robinson. She made plans to perform his second ablation. Because he’d had heart failure before, she had to make sure the irregular heartbeats weren’t a sign of his ventricles failing again.

AFib stems from the upper chambers (the atria). While it can cause symptoms and interfere with life’s activities, it alone isn’t life-threatening. An irregular heartbeat in the lower chambers (the ventricles), however, can be deadly. Known as ventricular fibrillation, or VFib, it can cause cardiac arrest.

Murphy underwent a cardiac ultrasound, MRI and electrical monitoring.

All the evidence suggested to Robinson, “There wasn’t any reason to be worried about his ventricles.”

Until they betrayed him in Colorado.

***

WOULD MURPHY STILL BE MURPHY?

In the 18 minutes between Murphy falling and paramedics arriving, he received four shocks.

Each time, Murphy opened his eyes, took a gulp of air and looked at Rick Perkins, the retired fire chief manning the AED.

“Come back to me, Murphy, I’m right here!” Perkins said, only to see Murphy’s eyes roll back, a sign that his heart had stopped again.

When the ambulance drove off, Perkins thought about his previous 131 save attempts.

He knew the number because he kept a scorecard. His tally: 3-128.

That is, Murphy would either be the 129th person he didn’t save or the fourth he did.

***

On the way to the hospital, Murphy received two more shocks. With the second, his heart rhythm stabilized. And with that, the top medical priority shifted to his brain.

How much damage did he endure from going so long without normal breathing and heart function?

How much damage did he endure from hitting his head so hard that he fractured his skull in five places and cracked four teeth?

The only way to find out was to wait. So doctors put Murphy into an induced coma, creating a gentle environment for his brain and body to heal.

Two days later, a doctor who specializes in critical care began reversing the process. The next 72 hours would determine whether Murphy was still Murphy.

Kate and Luke tried drawing him out. They read out loud his favorite verses from “the big book,” his recovery handbook, and the text messages, emails and social media posts that poured in.

They heard from tennis royalty such as Billie Jean King, Andre Agassi, Chris Evert, McEnroe, Roger Federer and Rod Laver; from business titans including Gates, Bill Ackman and other billionaires; and from a list of entertainers so glitzy that TMZ wishes it had contact info for all of them.

These weren’t empty “hopes and prayers” either. Sentiments were intense because friendships with Murphy are intense. People don’t love him despite his flaws; they love him for persevering, for his Murphy magic.

Close friends spoke to him by video chat or speakerphone. Gavin Rossdale, lead singer of the band Bush, sang his band’s hit song “Comedown.” Bush guitarist Chris Traynor played “Landslide,” the Fleetwood Mac song they covered. Friends from recovery read their favorite pages from the big book.

Around the 50-hour mark, the big question remained. Was Murphy still there?

To get a better idea, the critical care doctor whacked the middle of Murphy’s chest, jarring the sternum and ribs broken during his chest compressions.

Murphy squealed in pain. The doctor smiled and said, “He’s there.”

(Note: High-quality CPR often results in broken ribs. Like most survivors, Murphy is OK with the tradeoff.)

***

That night, Luke pulled out the pocket-sized version of the big book that Murphy carries when he travels.

The edges are worn, most pages dog-eared. Various passages are underlined in black. Luke turned to his favorite; he likes it because it stretches from page 66 (the year Luke was born) to 68 (the year Murphy was born).

While saying the last line, Luke felt Murphy squeeze his hand.

“Did that really happen?” Luke wondered. “Or do I just want to feel like it happened?”

The next morning, Duke’s 4th birthday, Luke arrived at the hospital before 7 a.m.

At 7:01, he called Kate: “He’s talking!”

When Kate arrived, Murphy asked her: “Where am I? What happened?” The words came out scratchy because a breathing tube had been in his throat.

“You had a cardiac arrest,” she said. “You’re in the hospital.”

Their eyes locked. She could tell he was processing the information.

“This is going to make a great chapter in my book,” he said, referring to an ongoing project.

Kate and Luke laughed. Murphy was definitely still Murphy.

Days later, Murphy received an implantable cardioverter defibrillator, or ICD, which is essentially an internal AED.

The device is about the size of a deck of cards. It’s under his skin, alongside his rib cage, with a wire that runs along the front of his chest, constantly monitoring his rhythm. If the ICD detects a problem, like the VFib that caused his cardiac arrest, it will correct it within seconds.

***

To recap, Murphy’s major heart problems include myocarditis, cardiomyopathy, heart failure, AFib and cardiac arrest caused by VFib.

It seems like one domino tumbling into another. Not necessarily.

“It’s more like a spoke-and-wheel thing,” said Robinson, Murphy’s electrophysiologist until she recently moved to Corvallis, Oregon. “Myocarditis is at the center. Everything else is a spoke coming off it. It’s quite a medical story.”

An obvious question is how much Murphy’s years of using drugs and alcohol contributed to his heart problems.

Robinson looked into it. Everything indicated the bad luck of viral myocarditis; his sobriety had been key to his heart muscle recovery.

Scientific investigation continues. Murphy recently had his DNA sequenced by Dr. Joseph Wu of the Stanford Cardiovascular Institute in California.

Wu, president-elect of the American Heart Association, is seeking genetic variants related to irregular heartbeats. The information could be valuable for everyone, from Murphy’s sons to all patients.

“We still do not understand all the genetic-molecular-pathological aspects behind sudden cardiac death,” Wu said. “More research is needed and having volunteers who are dedicated to working with the AHA will accelerate scientific progress that will ultimately benefit clinical care.”

***

‘THERE AREN’T A LOT OF PEOPLE LIKE THAT’

In 2005, Steven M. Gootter went out for a run. He never returned. He died of cardiac arrest. He was 42, married, with two young children. He’d been in great shape, didn’t smoke and had no family history of heart disease.

His sister, Claudine Messing, and her husband, Andrew, started the Steven M. Gootter Foundation “to save lives by defeating sudden cardiac death through increased awareness, education, scientific research and the distribution of AEDs.”

Because Gootter had been an Arizona state champion tennis player in high school, the Messings picked a tournament for the charity’s annual fundraiser.

Seven-time Grand Slam champion Mats Wilander was the headliner for several years. In 2012, he couldn’t make it. Murphy agreed to take his place. Wilander called Andrew and said, “You’re going to absolutely love him.”

Sure enough, Murphy won over the crowd – and the Messings.

“Steve had a huge personality, a great sense of humor and was a phenomenal athlete – and I can give you the same exact description for Murphy,” Andrew said. “There aren’t a lot of people like that.”

Having learned about Murphy’s heart problems, the Messings sent a meaningful thank-you gift: an AED.

Murphy became a regular at their tournament. He learned all about performing hands-only CPR (“push hard and fast in the center of the chest to the beat of ‘Stayin’ Alive'”) and using an AED. He also absorbed statistics, such as:

- Each day, nearly 1,000 people going about their usual activities go into cardiac arrest.

- Less than 10% survive, mainly because such few receive immediate CPR.

- Those who do get CPR immediately are two to three times as likely to survive.

Murphy helped the foundation raise enough money to donate almost 500 AEDs to schools, YMCAs, churches, synagogues and law enforcement officers in Southern Arizona. Those devices have led to many lives saved. The Gootter Foundation also supports Wu’s lab.

Because Murphy has gone from ambassador to living proof of the foundation’s mission, it’s rebranded.

The new name: the Gootter-Jensen Foundation.

Its new focus: “My hope is to ensure that wherever there’s a tennis court, there’s an AED,” Murphy said.

As for the AED from the Messings, it remains at Murphy’s house – fully charged, in a prime location. All his neighbors know where to find it should anyone ever need it.

***

A MUCH-NEEDED TIME OUT

Murphy arrived home from Colorado hardly able to walk the quarter mile to his mailbox.

He was sensitive to light and noise, lingering symptoms from a concussion caused by the collapse. The fall also made him nearly deaf in his left ear.

He needed lots of quiet. It was tough to find with a 4-year-old mini-Murphy running around the house.

As a former athlete, particularly one from a family raised to never quit, Murphy tried pushing through it all.

He couldn’t. He had panic attacks. He struggled to concentrate at a time when he needed more concentration to adjust to the hearing loss.

Enough people told him to take a “time out” that he reluctantly did. It wasn’t until June that he returned to his job.

Murphy is executive vice president of corporate development for WEconnect Health Management, a company he co-founded in 2014 with a friend also in recovery. They combined their experience and belief in the power of recovery with her skills as a serial entrepreneur to create a mobile app that provides resources, services and support for anyone curious about recovery from substance use disorder. They’ve since added tools for mental health.

***

Once Murphy regained the 30 pounds he lost in the hospital, his physical recovery progressed quickly.

A typical day now includes running 2.8 hilly miles, swimming in Lake Washington (often with Hemingway, his gray Australian Shepherd-poodle mix), riding his stationary bicycle, lifting weights and – yes, and – playing tennis. He strictly follows a heart-healthy diet.

He considers himself in the best shape of his life, which is saying something.

The bigger challenge was clearing his mental fog, a buildup of everything he faced cognitively and emotionally.

***

In his solitude, Murphy often thought about how things could’ve played out differently.

What if his heart stopped earlier in the day when he was swimming alone with Duke? What if trained lifesavers hadn’t been so close?

Then he heard about a man who went into cardiac arrest at his kid’s tennis tournament. The facility didn’t have an AED. The man died.

“That really cemented in his mind, ‘Holy smokes, what happened to me is somewhat of a miracle,'” Kate said.

The ICD gives Murphy peace of mind. However, seeing it protrude is a reminder that he has a glitchy heart. Another reminder comes every Monday morning – a blinking red light from a device on his nightstand indicating he needs to upload information from his ICD.

Then there’s all the guilt he carries.

The more Murphy understood about what happened, the worse he felt about the stress and pain his loved ones endured. He blamed himself.

Aftershocks continue, too.

Every time Duke hears a siren or sees an ambulance, he fears it’s for Daddy. He wants nothing to do with tennis because Daddy got hurt playing tennis.

Luke, meanwhile, struggled with going to work on the court where Murphy almost died. “I tried to rewire the anxiety I felt, but it was just too much,” he said. He gave up the job in January. He still experiences flashbacks and nightmares.

***

Murphy’s first visitor at home following his cardiac arrest was his therapist.

“Why am I still here?” he asked her.

“We’re going to find out,” she said.

Murphy trusted the big book’s principle of doing the next right thing. Now that his body and mind are stronger, he’s decided the next right thing is working with the American Heart Association to share his story.

“I’ve never been more aware of the gift that I have in this moment to be here, breathing and alive today,” he said. “My whole life – physically, emotionally, spiritually – has been reborn. The idea that my story could be helpful to any family in any way is without a question why I’m still here.”

***

The final piece to the puzzle of Murphy’s story involves a documentary about his life.

Work started two years ago. Filmmakers were in final edits when Murphy’s heart stopped. Needing to include this plot twist, they went back to work. The documentary is expected to come out in the spring.

The title remains the same. It’s even more fitting now:

“Born to Serve.”

Stories From the Heart chronicles the inspiring journeys of heart disease and stroke survivors, caregivers and advocates.

If you have questions or comments about this American Heart Association News story, please email [email protected].