For almost 19 years, whenever Tiffany Vara described the worst day of her life, she always included a particular word: unsuccessful.

As in, when her 2 1/2-year-old daughter, Abbie, was pulled from the bottom of the family’s swimming pool, the 10 minutes of CPR that Tiffany performed was unsuccessful.

The word seemed to fit. After all, over the next 11 years, Abbie made sounds but didn’t really speak; she twitched some muscles but couldn’t really control them. Then her fragile body wore out.

It wasn’t all bad, though.

A sassy tomboy before the accident, Abbie maintained that spirit after. Like the morning of her oldest brother’s college graduation, when she used a new communication method to declare: “I am different, but smart.”

Wordlessly, Abbie found ways to connect with countless people. And she developed an astounding bond with a sassy red quarter horse named Pu.

Tiffany, meanwhile, could never let go of the fact Abbie experienced “a preventable injury that was not prevented.” Guilt drove her to make her daughter’s second life the best it could be. Tiffany’s devotion is why, as difficult as those 11 years were, sometimes they were dazzling, too.

Now, more than eight years after Abbie’s death, there’s a new final chapter to this tale – a twist that puts a new perspective on the entire story.

To truly grasp it, however, you need to understand everything that led up to it.

***

Abbie’s first life

The morning everything changed – May 3, 2004 – Abbie did what she always did. She pulled out all her clothes to decide which she’d wear.

She probably wanted something extra special. Because, for the first time, her little toenails were covered with nail polish – bright pink, a treat Tiffany gave her the day before as they were getting dressed for church.

Once dressed, Abbie went outside. She dragged her plastic slide set next to a pen where her four brothers were raising rabbits. She then clambered her way up and into the pen, alongside the bunnies. One by one, she set them free.

Tiffany, the four boys and a 16-year-old cousin who was living with them spent the next hour searching in shrubs and under cars while Abbie rode around on her tricycle, enjoying the chaos. Once things calmed down, everyone found it hilarious, allowing Abbie to avoid punishment.

“Jesus keeps me safe!” she said between giggles. “Jesus keeps me safe!”

***

Tiffany and Ray Vara were done having children. Until they decided they wanted a daughter.

They planned to adopt. They had a home study set up with the adoption agency when Tiffany woke up feeling ill on Christmas Day, 2000.

“I just kind of have the flu,” she told Ray.

Nope. She was pregnant. They stopped the adoption process and prepared for the arrival of a fifth son. It seemed so inevitable that they picked only one name: Jack Logan Vara.

During the delivery, Ray said, “We have a daughter!” The news wasn’t the only thing that stunned Tiffany. So did the tone of Ray’s voice – a raspy, reverent whisper. Becoming a girl dad had already changed him.

Needing a name, they pulled out the list they’d made for previous pregnancies. It was in alphabetical order. On top: Abigail. When Ray learned its Hebrew origin means “my father is joyful,” the search was done. Tiffany laid claim to the middle name.

She chose Faith.

***

Tiffany grew up in Salem, Oregon, the older of two sisters raised by hard-working parents. To pay for her college of choice – Santa Clara University in California – she earned an ROTC scholarship.

Never much of a military person, she arrived on campus braced for “gruff people in a rigid hierarchy.” Instead, she felt part of a family. After graduating, she joined the Army Medical Services Corps.

She worked her way up to captain. She served in Somalia. She also met Ray, a fellow officer.

After one son, then another, along came twins. At that point, they decided it was time to leave the service. He became a hospital administrator; she became a full-time mom and homeschool teacher.

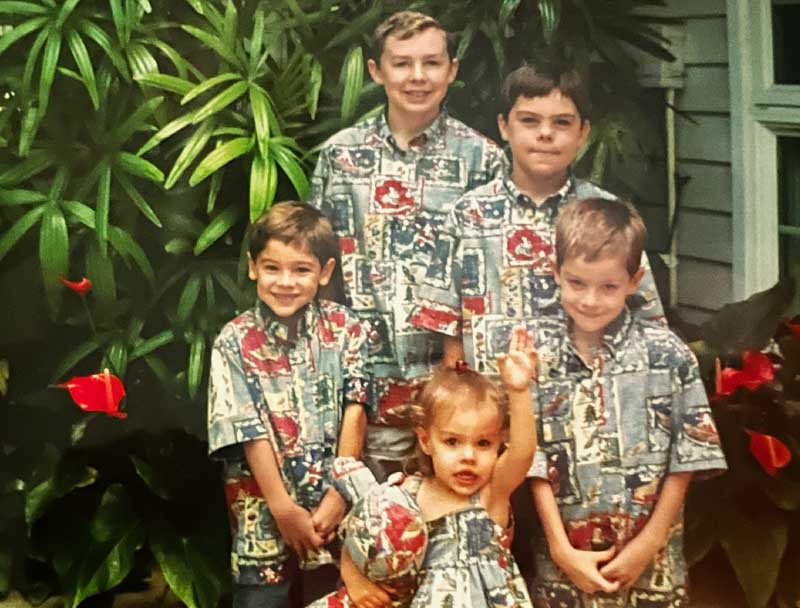

Homeschooling made the Vara boys classmates; their already close relationship became even closer. When Abbie arrived, the boys doted on her as much as their parents. The oldest son considered her “my baby.” The twins considered her their playmate. The second son was so comforting to Abbie that by age 2, she usually snuck into his bed in the morning.

Abbie was always trying to keep up with her big brothers, particularly in the school room. She learned basic math alongside the twins, and “perro” and “gato” (“dog” and “cat”) from the Spanish software the oldest boys used.

But her most clever trick involved her daily sippy cup of chocolate milk. Her brothers knew she was only allowed one. By asking each of them separately, she could finagle four.

***

Abbie was in diapers when the Varas moved from Los Alamos, New Mexico, to Honolulu. They bought a house that was L-shaped; every room faced their swimming pool. The skinny end of the L was a second living area that Tiffany turned into their “school room.”

That’s where everyone went after the rabbit rescue and lunch on May 3, 2004.

Abbie was sitting in Tiffany’s lap, watching her oldest brother work on the Spanish software when two women and four kids appeared in the doorway.

At church the day before, Tiffany had agreed to give these women some old clothes for a charity project. Still, Tiffany was surprised that these people, who’d never been to her house, had let themselves in and wandered all the way to the school room.

Now the women wanted a full tour.

Before leaving, one of the visiting kids wanted water.

Tiffany was at the kitchen sink, filling a glass, when she wondered where Abbie was.

***

Abbie had recently learned how to open the gate in front of the house. Given what happened with the rabbits, Tiffany thought Abbie was up to more mischief. Tiffany was dashing toward the front door when she heard screams coming from the pool.

She arrived to see Abbie on the decking, soaking wet and not breathing. Nobody knew how long she’d been underwater.

This is where Tiffany’s military training kicked in.

She knew how to remain calm under pressure. And she knew CPR.

***

Tiffany shook Abbie. Getting no response, she screamed for someone to bring her the phone.

She called 911, then told the kids to go out front to wait for the ambulance. They’d already seen too much.

As Tiffany gave Abbie chest compressions and rescue breaths, the girl’s eyes were open but vacant. This incandescent child suddenly seemed dark inside.

Tiffany continued CPR until paramedics arrived.

When the paramedics loaded Abbie into the ambulance, her skin was blue, her tiny toenails still radiant pink. Tiffany held one of Abbie’s feet and silently prayed: “You gave her to me. If you’re taking her back, and that’s your will, then I release her. But I still pray that she’ll survive.”

***

Abbie ended up going about 45 minutes between heartbeats. She surprised everyone by living past midnight.

She made it another day. Then several more, all the way through the following Sunday, which happened to be Mother’s Day.

If anyone was thinking Abbie might make a miraculous recovery, those hopes ended the next night when her monitors began blaring.

A neurologist told the Varas to follow her into a conference room. Tiffany saw the doctor grab a box of tissues along the way.

Growing pressure in Abbie’s skull was crushing her brain. It was time to say goodbye.

They brought in their boys, one at a time, oldest to youngest.

About 10 minutes after her last visitor, Abbie did something she hadn’t done since before entering the pool.

She tried taking a breath on her own. This meant she wasn’t brain-dead.

“I vote that we follow Abbie,” Abbie’s pediatrician said.

From that day on, things were … well, kind of like they’d been throughout Abbie’s life.

Everyone followed her lead.

***

Abbie’s second life

The Abbie everyone knew and loved was gone.

She’d never move, walk or talk like most people.

Yet there was a chance she retained some of her cognitive ability. Maybe a lot.

The essence of Abbie might still exist.

***

Abbie eventually figured out how to move her tongue. Not enough to eat (she used a feeding tube the rest of her life), but she could make utterances that indicated yes or no.

She eventually coaxed movement from her limbs. Not enough to walk, but she could swing a leg in a precise enough way to trigger a device that registered yes or no.

Abbie being Abbie, she only did those things if she liked the person asking the question.

One time, a caregiver turned on a Barbie video and Abbie became agitated. A few mouse clicks later, Abbie was watching a science video – and she was calm again.

“She never spoke,” Tiffany said, “but she communicated.”

***

Bodies are supposed to move and Abbie’s inability to do so caused problems.

Her muscles hardened. Her bones softened. Surgery was the only way to help her posture.

She underwent an 11-hour operation in which doctors cut both femurs to set them properly into her pelvis. While rehabbing, she broke both femurs again. Doctors ended up inserting rods into her leg bones.

Her hands contracted into fists. It wasn’t a big deal until a new communication technology came along that required her to use her fingers. That required surgery to open her hands.

Everything went great. But Abbie came away with a recovery device that Tiffany wasn’t expecting: metal rods that looked like paper clips sticking out from under each fingernail.

Oh my, she thought. What this girl endures …

***

Through her various ways of communicating, Abbie made one thing very clear to Tiffany about her near-death experience: There are horses in heaven.

It was especially fascinating for her to say that because, in her first life, Abbie wasn’t into horses.

In her second life, horses took on outsized meaning. “Braveheart” became her favorite movie because horses were so prominent.

A major benefit of Abbie’s corrective surgeries was that she became eligible for therapeutic horse rides.

When any person sits on a horse, the animal’s movements ripple through the rider’s body. The rider feels the same sensations as if they were taking those strides. For Abbie, this was as close to walking as she could get.

As great as that felt physically, imagine what it did for her emotionally and even spiritually.

Tiffany found one of the few facilities in Hawaii that used a double saddle for therapy rides. In this setup, instructor Patti Silva sat behind Abbie on the horse, while three or four volunteers walked alongside.

For a half hour, they’d go in circles inside a covered ring. Then they’d mosey down a “sensory trail,” riding under hanging pool noodles, riding over fallen telephone poles, stopping at a mailbox to grab a toy and delivering it to another mailbox and, the big finish, crossing a bridge that gave off a hollow sound as the horses walked over it. Everything from Hawaiian music to the “Chicken Dance” played over the speakers. Laughter always became part of the soundtrack, too.

Silva matched horses with kids based on personality and physical ability.

Abbie got along fine with her first horse. Then he retired. Silva decided to make Abbie the first therapy rider of a new horse in her stable.

This horse had been donated to the farm, then underwent the usual extensive training required to be entrusted with special needs children.

This horse arrived with the name Mariah, likely because her mane – a stunning combination of red, blonde and brown – matched Mariah Carey’s hair color. Silva had named a previous horse after her son’s Hawaiian name, so she gave this one her daughter’s Hawaiian name: Puali’i, or, in short, Pu.

Abbie and Pu fell so deeply in love that Silva practically felt like the third wheel on their dates.

With all special needs children, Pu turned back to see whether they were happy. With Abbie, Pu did it constantly.

“With other children, Pu might hear a noise and get startled – but when Abbie was there, she never, ever faltered,” Silva said.

Abbie rode every Tuesday at 10 a.m. for six years. It was the best hour of her week, especially during the four years she rode Pu. Tiffany’s too.

To this day, a reminder pops up on her phone at 9:30 a.m. every Tuesday.

***

Hours after Abbie’s accident, a big teddy bear of a physician put an arm around Tiffany and said, “This is not your fault.”

She told him it was her fault. “And,” she continued, “you have to let me hold that.”

When it was time for Abbie to first leave the hospital, doctors insisted that the Varas take advantage of the insurance-provided 40 hours of nursing per week. Tiffany pushed back. She said she didn’t want a stranger in her home. The real reason was that she didn’t want to acknowledge that she couldn’t care for her daughter.

Tiffany gave in, though, and quickly grew to trust and appreciate their nurse. A few months later, around Christmas, the nurse left for six weeks. Her absence almost broke Tiffany. Not just physically. Realizing how much she needed the nurse was another emotional blow.

There were so many emotional blows.

Guilt isn’t a strong enough word for what Tiffany felt about her role in the accident.

She knew people were judging her, talking about her. Yet nothing they said about her could come close to what she was telling herself. That may sound cliché but understand this: It took two years before Tiffany could close her eyes without seeing Abbie underwater, her precious face locked in fear as she wondered, “Where’s Mommy?”

The Varas also continued living in that L-shaped house for 10 more years, Tiffany seeing the pool through every window every day.

“For a long time, my life was like watching a kaleidoscope – a new dimension of horribleness kept being revealed,” she said. “I had to walk through the fire to get to the healing on the other side.”

***

At first, Tiffany wore her stronger-than-guilt sensation like a heavy robe. It weighed her down.

Over time, she learned how to bear the burden.

Her first bit of leverage came from the mantra “Love always wins.” She dubbed it “Abbie’s Law.”

Next, Tiffany worked to trust herself again.

Ray was extremely supportive, as were their four boys. The guys understood why they rarely – if ever – had both parents in the stands for a ballgame or a school play, but they appreciated that they always had at least one.

Tiffany and Ray also drew on their previous life experiences, including those years in the Army.

“We had grit by the metric ton,” she said. “Love combined with grit, it’s almost like making concrete.”

***

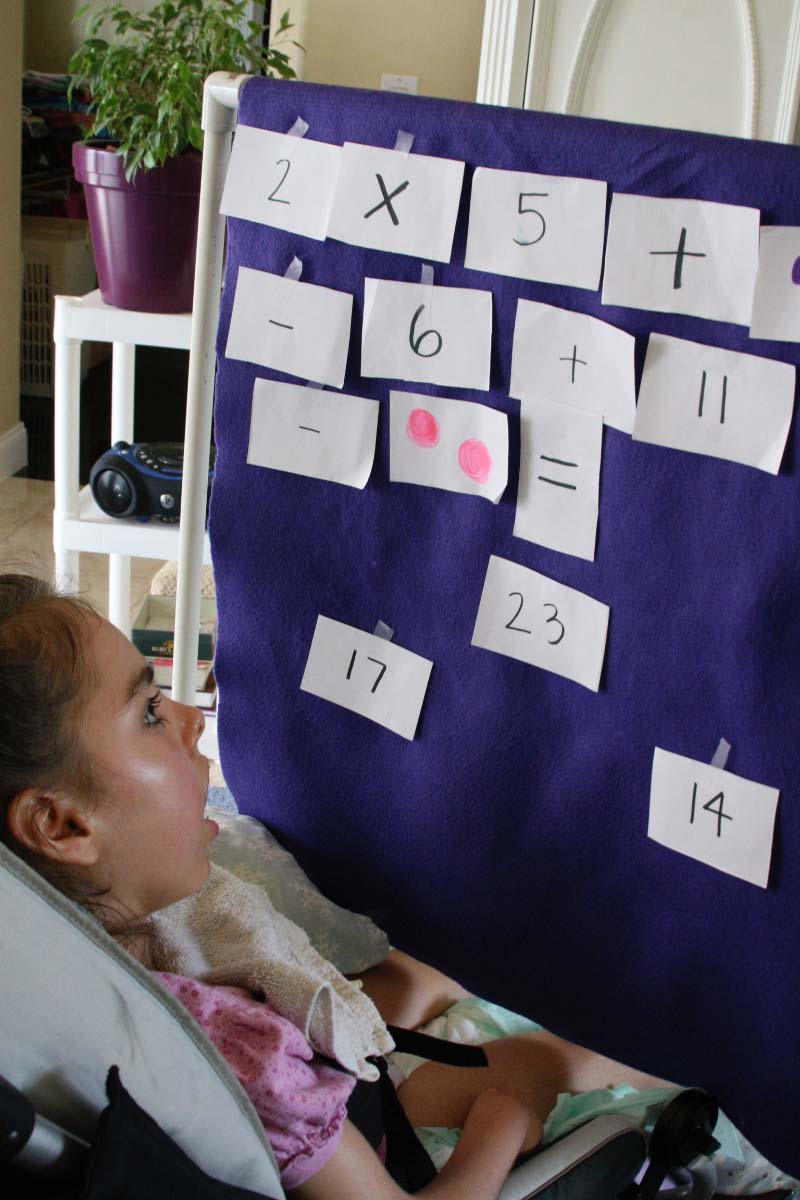

Abbie began homeschooling early in her second life. By second grade, she was doing multiplication and memorizing Robert Frost poems.

For third grade, she wanted to go to a real elementary school.

Things didn’t work out for many reasons. Among them: The curriculum bored her.

She was ready to try public school again for seventh grade.

Knowing how awkward and difficult middle school can be even under the best of circumstances, Tiffany feared another bad experience.

It went so well that Abbie returned for eighth grade.

She was so looking forward to the end-of-year banquet that she’d already picked out her outfit: a cream-colored shirt with a cute collar atop the pièce de résistance – jeans with an iridescent blue sheen and blue sparkles. The blue accents were meaningful because it was the school color.

***

Losing Abbie

Despite all she endured, Abbie had few life-threatening episodes the first 11 years after her accident.

Hospitalizations, however, were somewhat routine.

In April 2015, she went to the emergency room with a temperature of 103. Doctors thought she had the flu.

Abbie’s health deteriorated quickly. Her body began shutting down.

She surprised everyone by making it to Mother’s Day. She somehow held on for several more weeks, making it past her twin brothers’ high school graduation.

Two nights later – and two nights before her parents would be flying to Seattle for the college graduation of her second-oldest brother – Abbie needed a new IV. To make the change, the environment had to be sterile. Tiffany, Ray and Abbie’s twin brothers left the room.

Believe what you want, but Tiffany is convinced Abbie chose that moment, with her family in the hall, to spare them from witnessing her heart stopping.

***

Every Monday during Abbie’s final hospital stay, Tiffany called Silva to cancel the next day’s ride with Pu.

Pu wasn’t feeling well during that stretch, either.

She’d been OK enough to give rides for a few weeks, then she fell into a rut that confounded her vet. Every time one symptom resolved, another appeared.

Two days after Abbie died, Pu did the oddest thing. She walked through all the stables on the farm, pausing to make eye contact with each horse, goat and sheep.

“Horses that would normally be like ‘get away from me,’ they didn’t do that,” Silva said. “They just kind of accepted her visiting.”

Then Pu wandered out to a remote area on the farm to spare any person or animal from witnessing her heart stopping.

Pu died because fluid in her lungs put too much pressure on her heart.

It’s the same way Abbie died.

Before burying Pu, Silva did something she’d never done before and hasn’t since: She cut a few strands of the horse’s beautiful mane. Using lavender ribbon, she made two braids.

Abbie was cremated with one of them.

***

The epiphany

This past February, Tiffany and Ray were in New York for a series of events for the American Heart Association’s annual Heart Month. The Varas were involved because Ray was the AHA’s national board chairperson.

Each event focused on this year’s Heart Month theme: CPR.

Tiffany attended a luncheon hosted by AHA CEO Nancy Brown that focused on ways to get more people trained in CPR. Each table was asked to brainstorm ideas. The conversation became so lively that Tiffany felt compelled to say, “I’m really appreciating this conversation as a mother who had to give CPR to her child.” The comment was noteworthy because she rarely shares that, particularly not with people she’s just met.

That night, Tiffany attended the marquee event, the Red Dress Collection Concert. She met Nina Hamlin, mother of Damar Hamlin, the Buffalo Bills safety who – only a month before – had a cardiac arrest on the playing field during Monday Night Football. Thanks in part to immediate CPR, he made a full recovery.

Tiffany thought about what she and Nina had in common – and what they didn’t. Then, the next night, she met Damar. Seeing him do something as simple as walk up a flight of stairs, Tiffany marveled at what’s possible when the chain of survival plays out perfectly.

The next morning, Tiffany was part of an AHA crew at the New York Stock Exchange. She found herself in conversation with two women whose bond to the mission included loved ones who died of heart disease and stroke.

A woman from California shared the story of her mother dying of cardiac arrest, at home, alone; thus, she never had the opportunity to receive CPR. Tiffany told her new friends about Abbie.

The women cried.

“No, no, no,” Tiffany told them. “I know it is a sad story on the surface. But we didn’t live with her on the surface. We lived with her in the depths. There, it is not a sad story.”

***

Hours later, Tiffany and Ray were airborne, starting an 11-hour flight to Honolulu. She pulled out her laptop, opened a blank document and began working through everything on her mind.

Thinking back to that awful day, she typed – as always – that the CPR she performed on Abbie was “unsuccessful.” Only this time, seeing that word triggered a cartoon-like experience. Those 12 letters lit up and seemed to rise off the screen, everything else blurring behind it.

Staring at that word, an epiphany struck her.

Ever since the drowning, Tiffany lumped the CPR she performed into that day’s narrative, like Abbie having pink toenails.

Now she suddenly understood that she’d been viewing it all wrong.

By the time Abbie was pulled from the pool, it was too late for her to have a Hamlin-like outcome. The possible outcomes were the fate of the California woman’s mom or, well, what happened: Abbie’s second life.

For the first time, Tiffany realized that the CPR she performed made it all possible. It was the bridge to Abbie’s second life.

Had Tiffany not given CPR, those difficult, dazzling 11 years never happen.

Unsuccessful? Absolutely not.

Maybe not successful (full stop). But definitely successful enough.

Tiffany conjured the image of a spectrum of CPR outcomes. Hamlin was on one end, the California woman’s mom on the other. She envisioned Abbie in a box bridging both sides of the middle.

“Successful CPR is not defined by the outcome,” Tiffany said. “Success is knowing what to do and doing it. If you know what to do and you don’t stop doing it until help arrives, you’re successful. I was successful because I didn’t stop.”

***

After Abbie died, Tiffany took a step back.

A “withdrawal period,” she called it. She needed time and space to recalibrate after so many years of being emotionally exposed.

Throughout Abbie’s second life, Tiffany felt like a spotlight was on her. It ranged from actual positions of authority to the daily act of “pushing the most vulnerable part of my heart around in a wheelchair for all to see and judge.”

About a year later, she reemerged. Many leadership opportunities came her way because she was a mom who understood the challenges of raising a special needs child or because she’s the wife of a prominent businessman.

Then, a few months ago, she was offered a leadership role for another reason – because she’s a confident, capable woman who’s fallen in love with Hawaii and its people over the last 20-plus years.

Her position is with “Rediscovering Hawaii’s Soul,” a massive effort that aims to address the state’s toughest challenges while honoring the culture and values that make it special. Since accepting, she’s taken on a few more roles to make a meaningful difference in her community.

What’s changed? Why is she so willing to get involved in so many things?

The epiphany, of course. And her new understanding of what it means to be successful.