Knowing your blood pressure is a basic part of good health. But monitoring it at home can get complicated.

“It sounds easy – you buy a device, smack the cuff on your upper arm and push a button, right? It’s not so easy,” said Dr. Daichi Shimbo, co-director of the Columbia Hypertension Center in New York.

High blood pressure is a common condition in adults that’s associated with “really bad consequences,” such as heart attacks, strokes and dementia, Shimbo said. To diagnose and track it, doctors often ask people to check it at home. But even professionals can get tripped up on the proper procedures for home blood pressure monitoring.

Here’s help with some of the basics.

What exactly do those numbers mean?

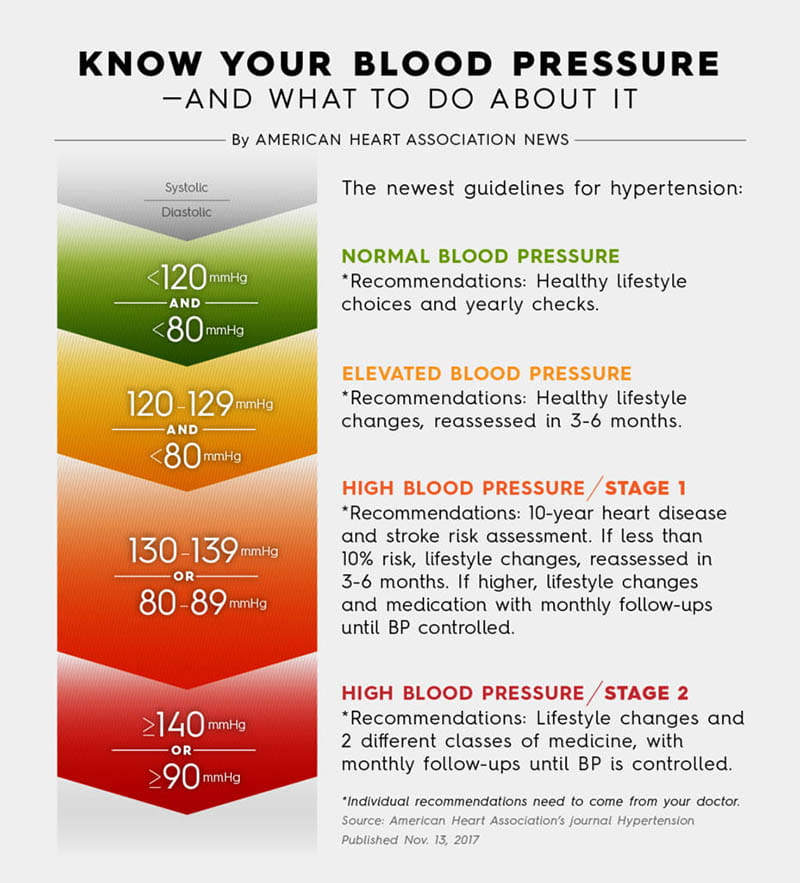

The top number in a reading measures systolic pressure, the force against artery walls when the heart beats. The bottom number, diastolic pressure, measures that same force between beats.

Dr. Karen Margolis, senior research investigator at HealthPartners Institute in Minneapolis, puts it this way: “The top number is when your heart is squeezing. The bottom number is when your heart is relaxing.” If you’re using a stethoscope, where a heartbeat sounds like “lub-dub,” the “lub” is the squeeze, and the “dub” is the relaxing.

The original measuring devices used mercury-filled tubes, delineated in millimeters. So blood pressure is expressed in millimeters of mercury.

Modern digital monitors don’t use mercury, but the principle is the same: A cuff around your arm cuts off blood flow in the artery inside your elbow. As the cuff is loosened, the “whoosh” of blood starting to flow again provides the systolic reading. When the noise stops, that’s the diastolic number.

The American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology recognize five categories of blood pressure in adults. A reading of less than 120/80 is considered normal.

View text version of infographic.

Where do I start?

Margolis and Shimbo agreed that proper self-monitoring of blood pressure starts with a validated device. Both co-authored a 2020 policy statement from the AHA and American Medical Association about home blood pressure monitoring.

Many devices tout Food and Drug Administration clearance. But the FDA does not validate the accuracy of devices it clears to be sold on the market, Shimbo said.

To find a validated device, start with the AMA website validatebp.org. An international consortium also lists validated devices at stridebp.org.

What kind of device should I use?

Upper arm cuff devices are preferred over wrist devices, according to the AHA/AMA report.

“I just find them really difficult to use,” Margolis said of the wrist devices. “They’re touchy. Your arm has to be in exactly the right position.” Still, people with medical issues that preclude compressing the arteries of both upper arms might need a wrist device, she said.

And cuff size matters. A “universal” cuff will work for most people, she said, but if you have a very slender or large arm, you’ll need an alternate.

Cuffless devices, including smartwatches, sound cool, Shimbo said. But few have been validated, so he considers them “not ready for primetime.”

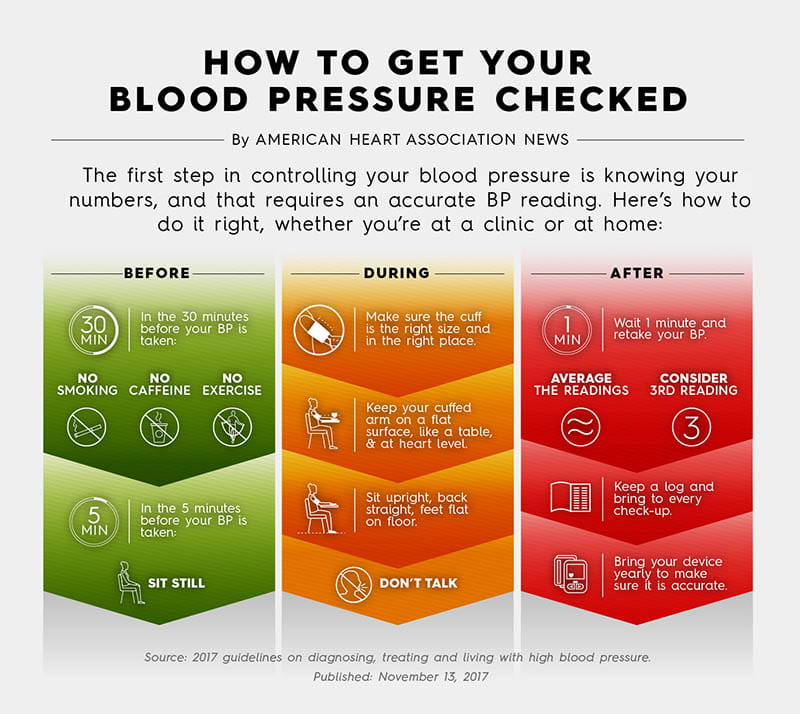

How do I prepare for a measurement?

This is “surprisingly hard,” Margolis acknowledged. Before taking a reading, you should avoid caffeine. Don’t exercise for 30 minutes beforehand. If you smoke, don’t smoke. Go to the bathroom. “Ideally, you want to wait until 30 minutes after you’ve had a meal.”

Then sit quietly without any distractions for five minutes, Margolis said. “And when I say no distraction, I mean don’t watch TV. Don’t listen to a podcast. Don’t read a book. Definitely don’t read the newspaper or listen to the news.”

What else is important?

According to guidelines from the AHA and ACC, sit in a chair that supports your back. Keep your feet flat on the ground. Don’t cross your legs. Position and support your upper bare arm at heart level. Keep your palm up and your arm muscles relaxed. Don’t talk.

Take two readings at least one minute apart.

Not following these steps can throw a reading off significantly. A reading taken over clothing, for example, can be off by 5 to 50 points.

View text version of infographic.

Does timing matter?

Blood pressure tends to be highest in the morning, decreases through the day and is lowest during sleep. To account for that, when diagnosing high blood pressure, you’ll be asked to take two readings in the morning and two in the evening over the course of a week.

“I would follow the advice of your doctor for how often to monitor,” Margolis said. For example, people whose readings are consistently normal wouldn’t need to check so often.

What if the reading doesn’t match what’s in the office?

That’s one of the things home monitoring is looking for, Shimbo said.

Some people get “white coat hypertension,” which is when readings are high in a doctor’s office but not outside the office. Others experience “masked hypertension,” where readings are normal in a doctor’s office but high outside the office.

Put another way – a reading in a doctor’s office will say what your blood pressure was during the brief time you’re in the exam room, Shimbo said. “But you spend all of your life outside the doctor’s office. Don’t you want to know what your blood pressure is in the real world?”

If you have questions or comments about this American Heart Association News story, please email editor@heart.org.