More stroke patients will be eligible for two critical treatments proven to reduce disability, according to new guidelines from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association.

The guidelines(link opens in new window) issued Wednesday cover acute ischemic stroke, the most common type of stroke, one that is caused by a blood clot that reduces or stops blood flow to a portion of the brain. Stroke is the second-leading cause of death in the world and a leading cause of adult disability. It kills about 133,000 Americans every year, and occurs in the U.S. about once every 40 seconds.

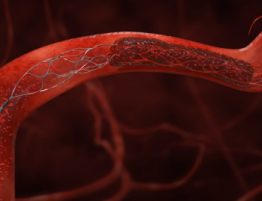

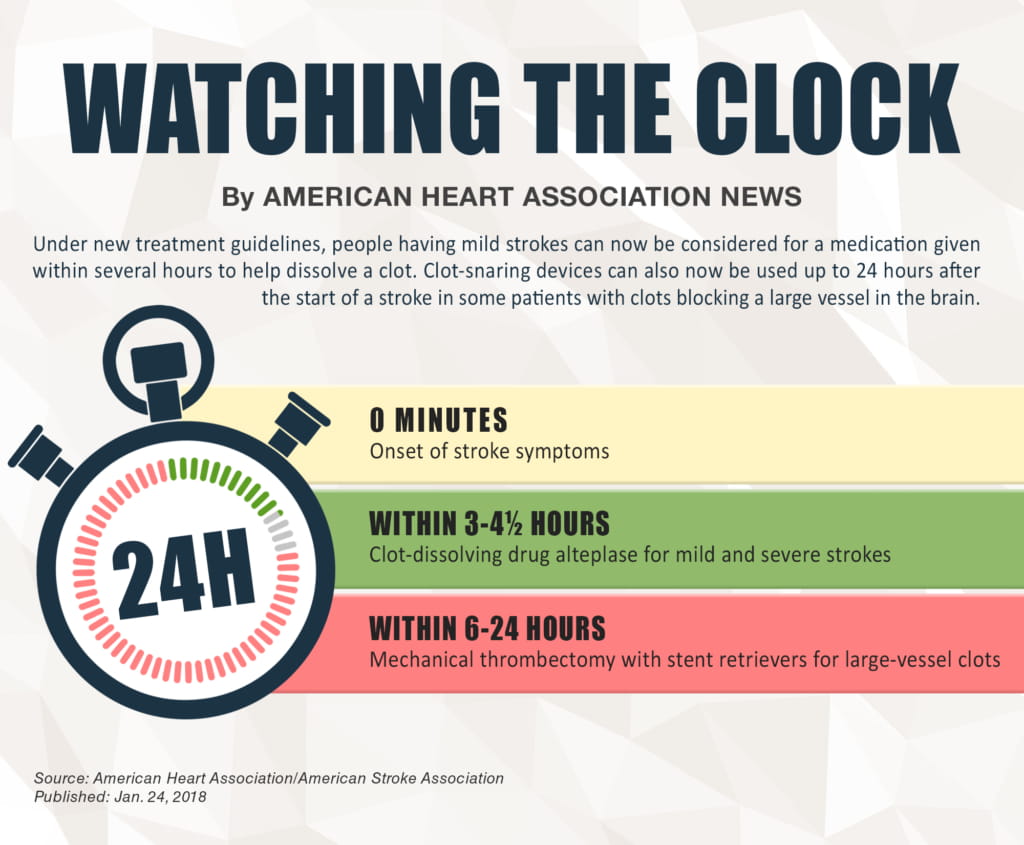

The guidelines recommend more people should be considered to undergo a procedure called mechanical thrombectomy, in which doctors remove blood clots using a device threaded through a blood vessel. In addition, the guidelines suggest that more people should be considered eligible for a clot-dissolving IV medication called alteplase.

Some patients may now have mechanical clot removal up to 24 hours after symptoms begin. The limit used to be six hours, but new research showed that some carefully selected patients may benefit even after an extended amount of time.

“This is going to make a huge, huge difference in stroke care,” said Dr. William J. Powers, guidelines writing group chair and chair of neurology at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine in Chapel Hill.

The clot retrieval procedure requires a physician to thread a catheter through an artery, using a clot-grabbing device within it to reach and remove the clot.

Patients may qualify for the procedure if they have a blood clot in a large artery inside the head supplying part of the brain. This type of clot may not respond well to IV medication alone, can cause serious complications such as brain swelling, and can lead to considerable disability or death, said Dr. José Biller, a guidelines author and chair of neurology at Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine in Illinois.

“Removing blood clots from large arteries can mean the difference between stroke survivors being independent versus being dependent on others, which makes a big difference in their quality of life,” Biller said.

Up to 20 percent of all ischemic stroke patients are currently eligible for clot removal, Biller said, a number he expects to grow under the new guidelines and with further research.

Mechanical clot removal was first recommended in 2015, and large hospitals offering specialized stroke care are staffed and equipped to perform the procedure, Powers said. Expanding the window of eligibility will require more regionalized, coordinated approaches to stroke care, he said.

Alteplase was approved to treat ischemic stroke in 1996 and remains the only medication approved by the FDA to dissolve clots. Alteplase is in a class of drugs known as tissue plasminogen activators (or tPA). It has been proven to decrease disability when given promptly.

The guidelines relax the “very, very rigid” guidelines established when alteplase was first used, Powers said.

“The way we look at alteplase used to be green and red,” he said. “Green go, red stop. Now we’ve taken some of the reds and made them yellow.” Previously, some patients who had milder strokes, recent surgery or spinal tap were not eligible, Powers said.

View text version of infographic

The new guidelines were published in the American Heart Association’s journal Stroke and announced at the American Stroke Association’s International Stroke Conference. Based on a review of more than 400 research studies, the guidelines replace the 2013 guidelines and all subsequent updates, Biller said.

The guidelines will hopefully increase and harmonize care in the U.S. and all over the world, Biller said.

For the public, the most important message remains recognizing the signs and symptoms of stroke and calling 911 immediately, Powers said. Stroke patients do better the faster they get treatment, he said.

“You shouldn’t make the decision about whether you’re having a stroke, and you shouldn’t wait around to see if it goes away,” he said. “Time matters. If you can get to the hospital even 15 minutes earlier, it really matters.”

Getting help quickly paid off for Terry Summers of Kansas City, Missouri, after his recent stroke.

In August 2017, he started slumping to one side and his speech suddenly became garbled. The 61-year-old attorney’s son, Sean, immediately recognized the stroke warning signs and called 911(link opens in new window).

Arrowhead Stadium in January.

(Photo courtesy of Terry Summers)

Treatment with alteplase began minutes after the symptoms started, and continued with mechanical clot removal at a nearby hospital. Summers was feeling better the next morning, and two weeks later he was back at work. Today he has occasional headaches and slight weakness on his left side, but no other lingering effects of the stroke.

Awareness helped – Sean’s mother is a stroke nurse who had drilled the signs of stroke into his head, Summers said. And, of course, taking immediate action to get the proper treatment was also crucial.

“I wouldn’t have called 911,” said Summers, who is glad his son was there to do it. “Timing has everything to do with the fact that I’m in one piece.”

Editor’s Note: This story was updated April 17, 2018, to remove information about telemedicine.

If you have questions or comments about this story, please email [email protected](link opens in new window).