Many of the roughly 15.5 million Americans with coronary heart disease will receive new advice regarding whether and how long to take aspirin combined with another blood-thinning antiplatelet to prevent clotting under updated guidelines(link opens in new window) released Tuesday by the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association.

For some patients, this will mean a shorter time on so-called dual antiplatelet therapy, or DAPT – for example, six months instead of the 12 months commonly recommended under previous guidelines.

But others could see their time on the therapy lengthened, such as those with a greater risk of clotting or a low risk for bleeding problems sometimes seen with aspirin and antiplatelet drugs like clopidogrel, prasugrel and ticagrelor.

Among the major changes:

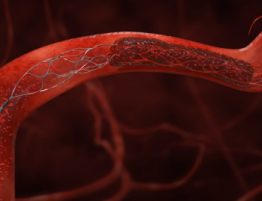

- Patients with stable ischemic heart disease, a condition that affects blood supply to the heart, who have received a drug-eluting stent to open a blocked artery need DAPT for only six months instead of 12 months. Even then, it might be reasonable to reduce the duration to three months in the face of high bleeding risk, or increase the time past six months if the risk of bleeding is not high.

- A new recommendation to resume DAPT in acute coronary syndrome patients after a coronary artery bypass graft, as well as in patients who receive a heart stent and subsequent bypass – an area where the guidelines were essentially silent before. Other bypass surgery patients may also be considered for a year of DAPT.

- Patients treated with a drug-eluting stent should wait six months rather than a year to have other types of elective surgery not related to the heart.

- In patients who have had a heart attack, 12 months of DAPT is generally recommended, but doctors are told it might be reasonable to discontinue treatment after six months if bleeding risk is high or to continue DAPT past 12 months if there isn’t such a risk.

- Because of the increased bleeding risk with little additional protection against clotting, the recommendation to use low-dose aspirin – 81 milligrams daily – has been strengthened. The aspirin component of DAPT is usually continued indefinitely.

The big take-away from the updates, published online in Circulation, may be a greater emphasis on tailoring treatment to the individual patient.

“Doctors and patients should weigh the benefit-risk ratio of either shorter duration DAPT or longer duration DAPT,” said Glenn N. Levine, M.D., chair of the group that put together the updated guidelines and director of the cardiac care unit at the Michael E. DeBakey Medical Center at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

Eric Bates, M.D., a professor of internal medicine at the University of Michigan and another member of the writing group, likened the new approach to a teeter-totter, with high risk of clotting adding weight to the argument to extend DAPT, and a patient’s high risk for bleeding pushing down the other side.

The guidelines provide a list of factors that increase clotting and heart attack risk, as well as a list of factors that suggest an increased risk of bleeding.

The style of the updated guidelines represents a “sea change,” according to Richard Becker, M.D., physician-in-chief and director of the University of Cincinnati Heart, Lung and Vascular Institute. He predicts the more approachable way it presents the information will lead to a greater embrace by busy doctors.

In updating the guidelines, the ACC/AHA Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines considered new research into the risks and benefits of longer and shorter duration DAPT, as well as the benefits from newer-generation drug-eluting stents that might justify shorter treatment.

Also, Bates said, there was a need to bring the sometimes-conflicting DAPT guidelines contained in six different heart disease treatment guidelines – for bypass graft surgery, catheter-placed stents and patients who have had a heart attack, among others – into harmony.