Consuming high levels of sodium and low levels of potassium may increase the risk for cardiovascular disease, according to a new study that sought to reaffirm the role sodium plays in cardiovascular disease.

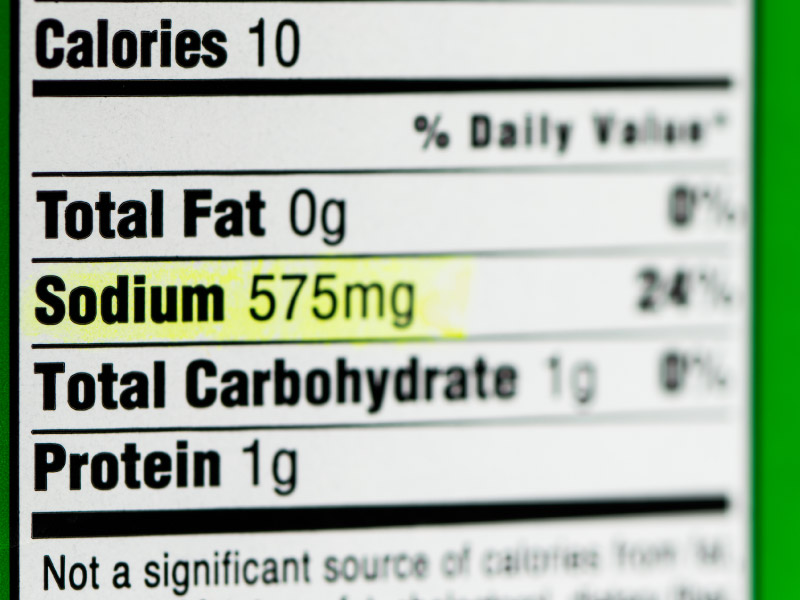

On average, Americans eat about 3,400 milligrams of sodium each day, much of that from store-bought packaged foods and restaurant meals, according to federal dietary guidelines. That’s much more than the limit of 2,300 milligrams a day of sodium recommended by the American Heart Association, with an ideal limit of no more than 1,500 mg per day for most adults.

Too much sodium in the bloodstream pulls water into the vessels, increasing the volume of blood flowing through them. That can lead to high blood pressure and an increased risk of heart attack and stroke. Potassium helps lower blood pressure by lessening the effects of sodium.

However, past research that used less than ideal methods to assess sodium yielded mixed results, with some studies showing both low- and high-sodium diets are linked to cardiovascular disease.

In the new study, researchers tried to shed a brighter light on the topic with in-depth testing. The study was presented Saturday at the American Heart Association’s virtual Scientific Sessions and simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The researchers examined data from 10,709 generally healthy adults who were an average of 52 years old. They were participants in six different studies across the U.S. and Europe. Their sodium and potassium were measured with at least two 24-hour urine samples, meaning all urine produced in a full day, which is considered the optimal method.

During an average follow-up of 8.8 years, there were 571 cardiovascular disease events such as a heart attack or stroke. The researchers found that higher sodium levels, lower potassium levels and higher sodium-to-potassium ratio were all associated with higher risk.

After adjusting for other cardiovascular risk factors such as age, smoking status, cholesterol and diabetes, participants with the highest levels of sodium in the urine (an average of about 4,700 mg) were 60% more likely to have a cardiovascular event than those with the lowest sodium levels (about 2,200 mg). Those with the highest levels of potassium (about 3,500 mg) had a 31% lower risk of cardiovascular events than those with lowest levels (about 1,750 mg).

The study’s lead author, Yuan Ma, said the results weren’t surprising.

“Our study helps clarify the controversy caused by previous studies regarding whether to reduce sodium intake from current levels in most populations, including the U.S.,” said Ma, a research scientist in epidemiology at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston. “We hope these important findings, together with consistent results from randomized trials, will speed up implementation of sodium reduction policies that will benefit the public by helping reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease.”

She urged people to read and understand nutrition labels to see how much sodium they’re consuming. It’s also important to eat more vegetables, fruit and potassium-rich foods such as bananas, sweet potatoes, spinach, peas, tomatoes and fat-free milk and yogurt. A medium banana, for example, has about 420 mg of potassium, and the average adult should get 4,700 mg a day.

Ma called for federal agencies to work closely with food companies and incentivize them to decrease sodium in their products, an approach used with success in the U.K. and other countries. In what Ma called “an important step,” the Food and Drug Administration issued guidance last month to the food industry to voluntarily reduce sodium in their products.

“We could reduce sodium intake significantly, population-wide, if the government issued relevant policies and the food industry gradually reduced sodium so that people would eat less sodium even without noticing it,” she said.

The research was limited because it is an observational study, which doesn’t prove cause-and-effect, and it mostly involved white participants. She said she’d like to see future research done on more diverse populations, including studies pinpointing the best ways to alter individual preference toward a low-sodium diet.

Dr. Lawrence Appel, who was not involved in the research, said the findings reaffirm the idea that “methods matter when it comes to studies.”

“There’s been a lot of noise from studies that have poor quality methods, which has left a lot of people scratching their heads. This study had rigorous method and reaffirms what we already knew: As sodium intake goes up, so does the risk of cardiovascular disease, and as potassium intake goes up, the risk goes down,” said Appel, director of the Welch Center for Prevention, Epidemiology and Clinical Research at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

He said the findings underscore the importance of adjusting your taste buds.

“Some people think low-sodium means low taste, but that’s not really the case,” he said. “By habit, we’re acclimated to a high-sodium diet, but if you’re gradually eating less sodium, your preference actually changes and high-sodium foods taste too salty.”

Find more news from Scientific Sessions.

If you have questions or comments about this story, please email editor@heart.org.