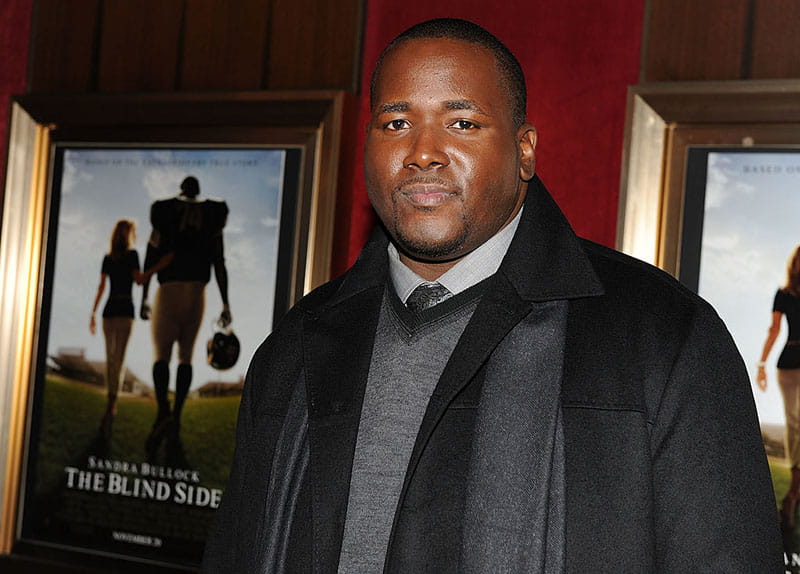

Quinton Aaron knows the power of a success story featuring a talented young man and a mother figure who helps him beat the odds. Those elements helped make the 2009 film “The Blind Side,” which he starred in alongside Sandra Bullock, a blockbuster.

That film was about football star Michael Oher, but Quinton’s life has its own Hollywood-worthy arc: A sudden rise to fame. The loss of the mother who guided him. A descent into despair. A diagnosis of the same heart condition she’d had.

And then – guided by other strong women in his family – a determination to not become a tragic figure.

“‘The Blind Side’ was based on someone else’s story,” said his cousin, Monique McGoogan-Sabage. “But Quinton has an incredible story of his own.”

Befitting his stature – he’s 6-foot-8 – Quinton said he has always dreamed big.

He was born in the Bronx, New York, in 1984 and began performing at an early age, imitating Batman and Michelangelo (the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle) and singing Michael Jackson songs around the house. “There were so many things I wanted to do,” he said. “And my mom just taught me to believe in myself, and never let anyone tell me that I can’t do those things.”

Quinton moved regularly but stayed surrounded by extended family. He also was shy, and targeted by bullies. But around age 9, his mother, Laura, suggested he get involved in drama classes at school. When he took to the stage, instead of taunting him, his classmates were enthusiastic.

“I can’t even describe the feeling I felt from that moment,” he said. “It was like, ‘I want more of it.'”

By 12, he was 6 feet tall and about 200 pounds. His aspirations were just as big. “I told my mom, ‘I want to be an action star. I want to be like Arnold Schwarzenegger.'” He intended to become the first Black James Bond.

A decade later, in 2007, his mom spotted the part that would change his life. While he’d been doing work in student films, she’d been scouting audition opportunities online. The description of the role for “The Blind Side” sounded so much like her son, she woke him up at 3 a.m. to talk about it.

He landed an audition and thought it went well. Then he spotted an established actor waiting his turn in the hall, and Quinton lost hope – although as a backup, he’d handed the director his business card, offering to work security.

His mom never doubted his acting success. But she wouldn’t live to see it.

Years before, Laura had been diagnosed with congestive heart failure, a condition where the heart is not pumping properly. She developed obstructive sleep apnea, characterized by snoring and disrupted sleep, and had trouble breathing. She was given medications, but her health continued to decline. Laura died in September 2008, at the age of 44.

It was before he’d officially landed the role. “One of the last things she told me about it was that it doesn’t matter whatever is going on right now – there’s no way they’re going to do that movie without me.”

She was right. But her loss devastated him.

Quinton, his brother, Jarred, and their mom had been “like the Three Musketeers growing up,” he said. He never knew his father, and his mother’s death meant the loss of “my best friend, and the only parent I had.”

“She was everything” to him, Monique said. “He had a wonderful grandmother. He had amazing aunts. He had cool cousins. But she was everything.”

Quinton set his grief aside, because he had work to do. He began working on “The Blind Side” in April 2009, and it was released that November. Its tremendous success let Quinton mask his pain in his work.

His blossoming acting career filled his days. He likened it to a noise that drowned out other thoughts. But when work tapered off, “all of that noise got quiet,” he said. “And then the fact that my mom is not here anymore got loud again.”

Overwhelmed by grief, Quinton fell into depression and depressive eating. “I would eat all the time, even when I wasn’t hungry,” he said. “And none of it was healthy.”

While filming “The Blind Side,” he weighed 370 pounds. By 2019, he’d hit 565. That May, he felt sick, “like a bad chest cold.” He lost his voice but resisted going to the doctor.

He was living in New Mexico and checked in with his great-aunt Jannie McGoogan, Monique’s mother. “She heard my voice and she was like, ‘Are you still sick?'” he said. “And I said, ‘Yeah.’ She said, ‘Boy, if you don’t get off that couch and take your behind to the hospital right now, I’m gonna fly out there and kick your tail!'”

He obeyed. Fans snapped photos of him being wheeled around. “I was completely bloated,” Quinton said. “My legs were swollen and sore all the time. It was just hard to breathe.”

The diagnosis was congestive heart failure.

Heart failure can have genetic roots, said Dr. Gregg Lanier, who has treated Quinton at Westchester Medical Center in Valhalla, New York. Quinton has such a history, plus risk factors such as sleep apnea and obesity.

Medications are crucial for controlling heart failure, he said. But lifestyle changes can help.

Which is what Quinton set out to do. Eventually.

The year 2020 “was dreadful,” he said. He was hospitalized once for COVID-19 and twice for heart failure. He tended to be “a nomad,” moving around for work, and took his medications sporadically.

But in late 2021, he learned he also had diabetes. “And I was like, enough is enough.”

His weight has gone up and down throughout his life. To get in shape for his “Blind Side” role, he’d dropped more than 100 pounds. That involved twice-a-day workouts with a trainer and chef-prepared meals.

He’d have none of that this time. But he forged his own healthy path.

Quinton started limiting the hours he ate, doing intermittent fasting, which research has associated with weight loss and a lower risk for heart failure. He rethought his eating habits so that he stopped as soon as he felt full, instead of cleaning his plate. He made sure that most of his meals were healthy. “I’m not depriving myself fully of everything that I love,” he said. “I’m just eating a lot less of it.”

And he stayed consistent with his medications, which keep fluid from building up in his body. As a result, he said, “The weight started falling off, and I lost, in total, 170 pounds.”

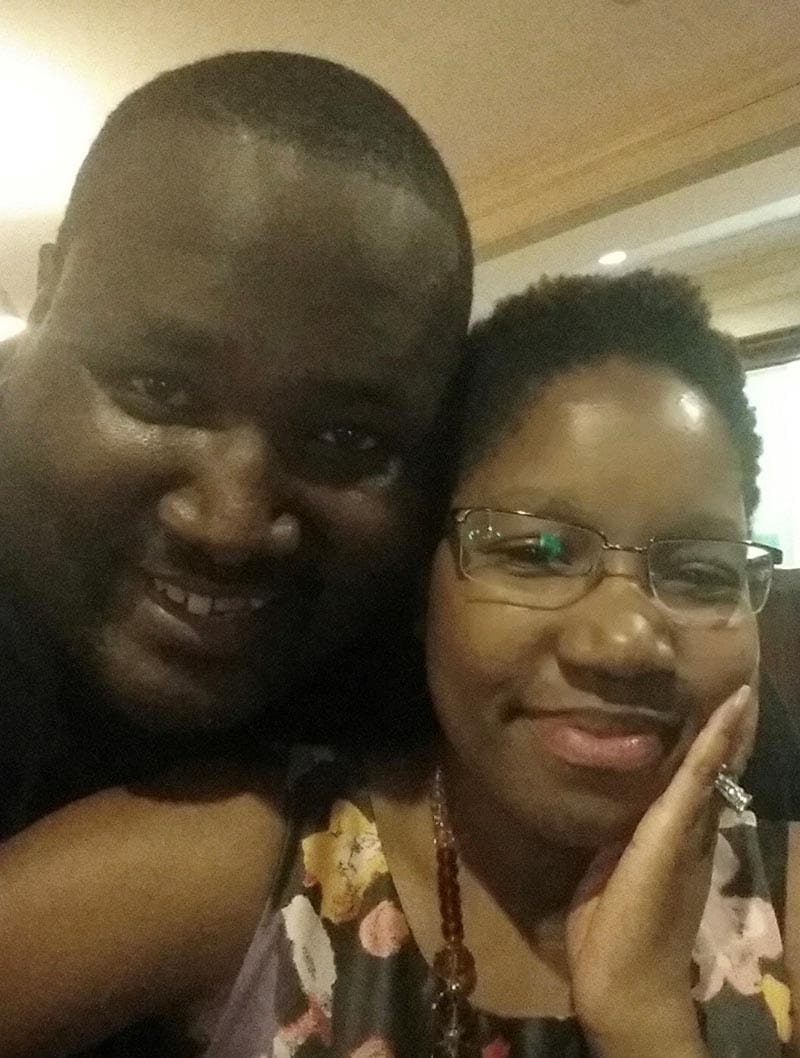

Monique admires her cousin’s determination. She also knows he’s had help.

“The women in our family are incredible,” she said. “Not only are they great cooks, but they’re intuitive to what’s really going on. Our family is one of those families where if you say, ‘I’m fine,’ we’ll know if you’re really fine. And that intuition, I think, for many of us has kept us alive.”

When Quinton’s mother died, Aunt Jannie had taken him under her care. “He was very, very close with my mother,” Monique said, “and kind of adopted my mother as his own.”

But Aunt Jannie became ill herself and would succumb to factors that included heart disease in May 2021. She was 73.

“After she passed, he was like, ‘Well, Monique, I guess you’re the one now,'” Monique said, laughing. “And I said, ‘OK.'”

That felt natural to her, she said. And important.

Monique, who supervises an outpatient clinic in Valhalla, thinks that too many Black families are reluctant to discuss health. “A lot of people don’t go to the doctor as they should,” she said.

So she did what her mother would have done, and when Quinton was in town for her mother’s memorial service, Monique approached Lanier, a heart failure specialist, and arranged for him to see her cousin. Lanier now serves as a regular base for monitoring Quinton’s health wherever he is.

That’s important. “This will be a lifetime condition and will never go away for him,” Lanier said. “Even if his heart function improves, he’ll still require medications.”

The mainstay of treatment is lifestyle improvements, Lanier said, and anyone with heart failure needs a cardiologist who can regularly monitor weight, blood pressure and medications. Lanier also suggested that patients meet with a heart failure specialist to begin discussing what happens down the road.

Heart failure can worsen despite treatment, which is why Lanier considers it critical for patients to have access to medical centers that are up to speed on advanced treatments, which can include a heart transplant or implanting a mechanical pump called a left ventricular assist device, or LVAD.

But, Lanier said, “if he’s able to lose weight, maintain a healthy lifestyle and have uninterrupted medications, I’m hoping he’s going to do very well for another 10 or more years.”

Quinton proudly notes that a key measure of his heart’s pumping power, known as ejection fraction, has been improving. He also acknowledges that with his weight loss, which has plateaued of late, it’s easy to get off track.

But he’s determined – and active, doing public speaking, working on a music career, promoting a book project with a co-author in Austria. And he’s grateful to God and his family for the successes he’s had.

“My mom, my aunts, the women in my family, my grandma – they all played a big part of me becoming the man I am today,” he said. His father wasn’t around, “so everything I do is in honor of the women in my life.”

Monique is hopeful for her cousin. He knows how to overcome, she said. And surrounded by people who care about him – “not just family, but he has the right physicians” – she thinks he’s going to be fine.

“I can hear it in his voice when he’s really well, and when he’s not feeling well,” she said. “He has been doing well. And I love that.”

If you have questions or comments about this American Heart Association News story, please email [email protected].