In second grade, Emily Meister was performing as Gretl Von Trapp in the local high school production of “The Sound of Music” when she felt her heart beating unusually fast. She also sensed pressure in her chest.

The youngster from Wichita, Kansas, had consumed an energy drink to stay awake for the late-night show. Her physician suggested the overload of caffeine in the drink may have caused her discomfort.

The symptoms recurred periodically over the next two years. She always blamed them on caffeine.

Then, during a school sports physical, her pediatrician detected an irregular heart rhythm. The next day, a cardiologist ordered a series of tests, then had her wear a heart monitor. Wires from the device stuck out Emily’s shirt – a tough way to start fourth grade, recalled her mom, Lori Meister.

“There was no way to cover it with clothing,” Lori said. “She was so embarrassed.”

To make matters worse, Emily had an allergic reaction to the adhesive, leaving welts and scarring her skin.

A month later, Emily got her first diagnosis: premature ventricular contractions (PVCs), or a change to the normal heartbeat leading to an extra or missed heartbeat in the heart’s lower chambers. She was prescribed medication and advised to rest if she experienced symptoms during physical activity.

Her condition was scary because it was so unpredictable. Sometimes her heart beat too fast; other times too slow, causing her to get dizzy or faint.

“I’d feel fine and then stand up and feel my heart start beating really fast or feel a heaviness in my chest,” Emily said. “Sometimes it would even feel hard to breathe.”

Emily met with her cardiologist every four to six months, each time going home with a heart monitor to wear for a few weeks. In middle school, her medication was increased after testing showed she also had premature atrial contractions (PACs), which is pretty much the same condition but in the heart’s upper chambers.

Emily was still allowed to be active. She played soccer and participated on a cheer squad. By her sophomore year in high school, Emily’s symptoms became more frequent. After one particular workout, her pain was so intense that she took a quick-acting beta blocker her doctor prescribed for such situations. It didn’t help.

“It felt like my heart was going to explode,” she said.

More testing showed Emily now had a third heart condition: mitral valve prolapse, a condition in which the valve doesn’t close smoothly or evenly, bulging into the left atrium.

“It was hard to take in because I was used to having my heart hurt a certain way, but now it was worse,” Emily said.

Emily’s doctors have suggested her condition may be genetic. In addition to a family history of heart disease on both sides of her family, Lori also has mitral valve prolapse and Emily’s older sister, Elizabeth Meister, was diagnosed with PVCs in high school.

Emily continues to be monitored by her cardiologist and takes various medications. She experiences heart palpitations almost daily and has been told those may continue throughout her life.

As much as her life has been shaped by being a heart disease patient, the teen is taking charge of how it shapes her future.

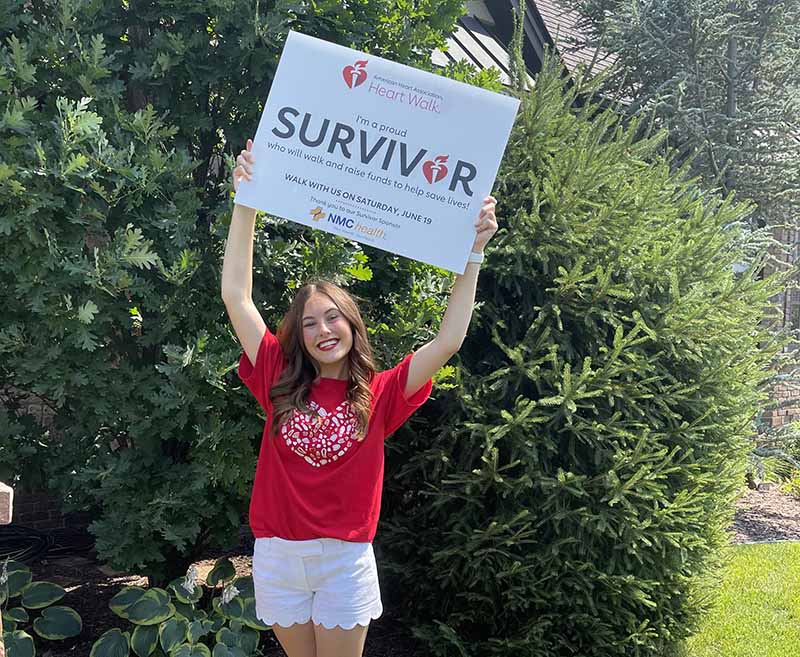

Emily became involved with the American Heart Association to use her story to promote research and awareness. She’s volunteered at fundraisers and created social media videos.

“When I was first diagnosed, my condition meant frustration for me,” Emily said. “As I grew up and got more involved and advocating for heart health, it became more of an opportunity to create a greater impact in the community.”

Now a high school senior, Emily plans to major in pre-med and hopes to find a career in pediatric cardiology so she can help patients like herself.

“Don’t let your conditions or something about you hold you down,” she said. “Find a way to use it to create a greater impact.”

Stories From the Heart chronicles the inspiring journeys of heart disease and stroke survivors, caregivers and advocates.

If you have questions or comments about this story, please email editor@heart.org.