A type of “bad” cholesterol could raise the risk for first heart attacks, strokes and death from heart disease, new research suggests. But the increased risk only appears in people who already have high blood pressure.

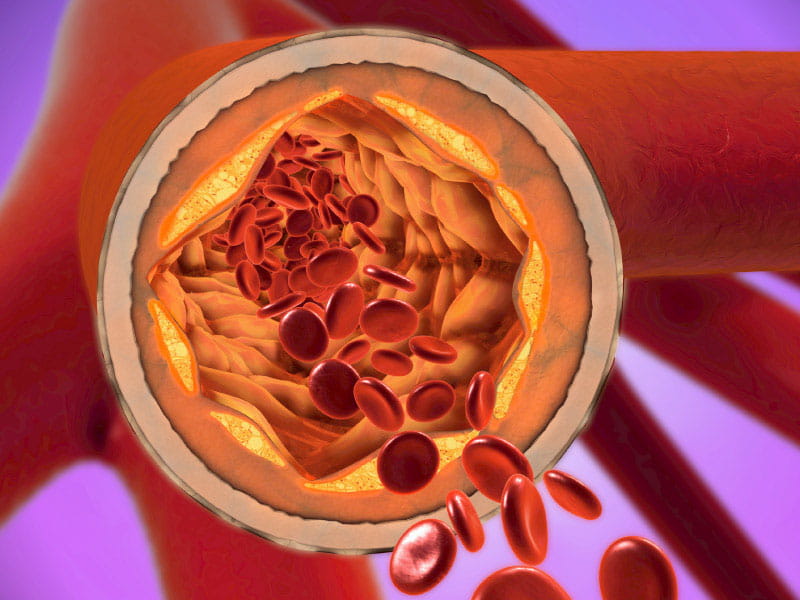

Lipoprotein(a), like low-density cholesterol (LDL), is a subtype of lipoprotein that can build up in arteries, increasing the risk of a heart attack or stroke. Lipoproteins consist of protein and fat and carry cholesterol through the blood.

Concentrations of lipoprotein(a) are largely set by genetics and unaffected by lifestyle.

Among people whose blood pressure is within the normal range, high levels of lipoprotein(a) did not raise the risk for cardiovascular events, according to the study published Tuesday in the American Heart Association journal Hypertension.

“We found that the overwhelming amount of cardiovascular risk in this diverse population appears to be due to hypertension,” lead study author Dr. Rishi Rikhi said in a news release. Rikhi is a cardiovascular medicine fellow at Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. “Additionally, individuals with hypertension had even higher cardiovascular risk when lipoprotein(a) was elevated.”

High blood pressure, also known as hypertension, is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Research shows that risk is even higher when a person has both hypertension and a lipid imbalance, called dyslipidemia, such as high cholesterol. But little was previously known about how lipoprotein(a) affects the risk among people with hypertension.

Using health data from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, investigators divided 6,674 study participants into four groups: people with lipoprotein(a) levels less than 50 mg/dl and no hypertension; people with lipoprotein(a) levels of 50 mg/dl or higher and no hypertension; people with levels less than 50 mg/dl and hypertension; and people with levels 50 mg/dl or higher and hypertension.

Since 2017, the American Heart Association has defined hypertension as a top number of 130 mmHg or higher or a bottom number of 80 mmHg or higher. But in this study, investigators defined high blood pressure as a top number of 140 or more, a bottom number of 90 or higher or if a person was taking medication to control blood pressure levels.

Participants in the study came from racially diverse populations in Baltimore; Chicago; New York; Los Angeles County; Forsyth County, North Carolina; and St. Paul, Minnesota. The participants did not have cardiovascular disease when the study began in 2000, and they were monitored over an average of 14 years for any cardiovascular events, including heart attacks, strokes, cardiac arrest and death from coronary artery disease.

The study suggested that lipoprotein(a) alone did not raise the risk for cardiovascular events. But when it was combined with hypertension, the more lipoprotein(a) that was present, the higher the risk.

Compared to people with low lipoprotein(a) levels and no hypertension, those with higher lipoprotein(a) and no hypertension had no increased risk for cardiovascular events. Only about 8% had an event in each group.

But both groups with hypertension saw an increase in cardiovascular risk, whether lipoprotein(a) levels were high or low. Among those with lower lipoprotein(a), 16.2% had cardiovascular events, as did 18.8% of those with higher lipoprotein(a) levels.

“The fact that lipoprotein(a) appears to modify the relationship between hypertension and cardiovascular disease is interesting, and suggests important interactions or relationships for hypertension, lipoprotein(a) and cardiovascular disease,” Rikhi said. “More research is needed.”

If you have questions or comments about this American Heart Association News story, please email [email protected].