A summary of sugar’s health effects can sound like the tagline for a Hollywood thriller: “It’s sweet and alluring. It’s a master of disguise. And tonight – it’s hiding in your refrigerator.”

OK, maybe not a successful thriller. But like a double agent, sugar can be both beneficial and dangerous. In its guise as added sugar, the emphasis is on danger.

“The research just keeps flowing about how bad it is, truly,” said Dr. Penny Kris-Etherton, the Evan Pugh University Professor of Nutritional Sciences, Emeritus at Penn State in University Park, Pennsylvania.

Being aware of how sugar works and where added sugar lurks can help you manage it, she said.

Natural sugars come in several varieties. Some, such as glucose and fructose, are just a single molecule.

Others consist of linked molecules. Sucrose (table sugar, usually derived from sugar cane or sugar beets) is made up of one glucose and one fructose molecule. Lactose, which can be found in milk, consists of one glucose and one galactose molecule.

None is inherently bad. Our bodies turn sugars and other carbohydrates into glucose that fuels red blood cells, the central nervous system and the brain.

Because sugars provide a quick way to get this vital energy, humans evolved to seek it out, and our brains feel rewarded when we find it.

Here is where the trouble begins.

Our ancestors had limited access to sugar, and that would have been natural sugar, such as the fructose found in fruits. Today, sugar is as abundant as suspects in a game of Clue. High-fructose corn syrup, molasses, cane sugar and honey all are types of added sugar.

The average adult in the U.S. eats about 60 pounds of added sugar a year, according to the American Heart Association.

When you eat sugar, it sets off a chain reaction in the body, Kris-Etherton said. As sugar is digested, your blood glucose level increases. To regulate it, the pancreas pumps out insulin, which lowers glucose in the blood. If you constantly eat sugar, the pancreas has to “keep pumping and pumping and pumping.”

Over time, that puts a strain on the pancreas, she said. When the pancreas can’t produce enough insulin to manage blood sugar, or the body becomes resistant to insulin, the result is Type 2 diabetes. Plus, excess calories get stored as fat, which can lead to obesity, a condition linked to both diabetes and heart disease.

The AHA recommends limiting added sugar to no more than 6% of calories each day. For most women, that’s no more than 100 calories a day, or about 6 teaspoons. For men, it’s 150 calories a day, or about 9 teaspoons.

You don’t need to be Sherlock Holmes to track down added sugar in your food. “It’s everywhere,” Kris-Etherton said.

Yes, you’d expect added sugar in a can of cola (41 grams, or about 10 teaspoons, in a 12-ounce can of one popular brand) or a cupcake (18 grams, or 4 1/2 teaspoons, per individually wrapped national brand cupcake). But you’ll also find it in ketchup (roughly a teaspoon of added sugar per tablespoon) and bread (a quarter teaspoon per white slice, and more than a teaspoon in one brioche bun). Added sugar can hide in fruit drinks as well.

In their attempts to cut back, some people turn to artificial sweeteners. Kris-Etherton is wary. The science on sweeteners is mixed, she said. “So, I think caution is warranted.”

People who are worried about sugar in their diet should be aware of the difference between added sugars and naturally occurring sugars that you’d get in a fruit or vegetable.

Although natural fructose is, at the molecular level, just another sugar, who it hangs out with matters. The company that fructose keeps in, say, a cup of strawberries (which has 8 grams, or 2 teaspoons, of total sugar), is completely different from the company it keeps with something like a sugar-sweetened beverage, Kris-Etherton said.

For starters, that serving of strawberries (or bananas or even corn) comes with vitamins and nutrients. It also comes with fiber, which slows the processing of sugar in the digestive tract and limits spikes in blood glucose.

Kris-Etherton pointed to a sugar study released in September in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. It found that while the fructose from added sugar and juice was associated with a higher risk of coronary heart disease, the fructose from fruits and vegetables was not.

Her advice for people who want to cut back on added sugar is to start by keeping an eye out for it.

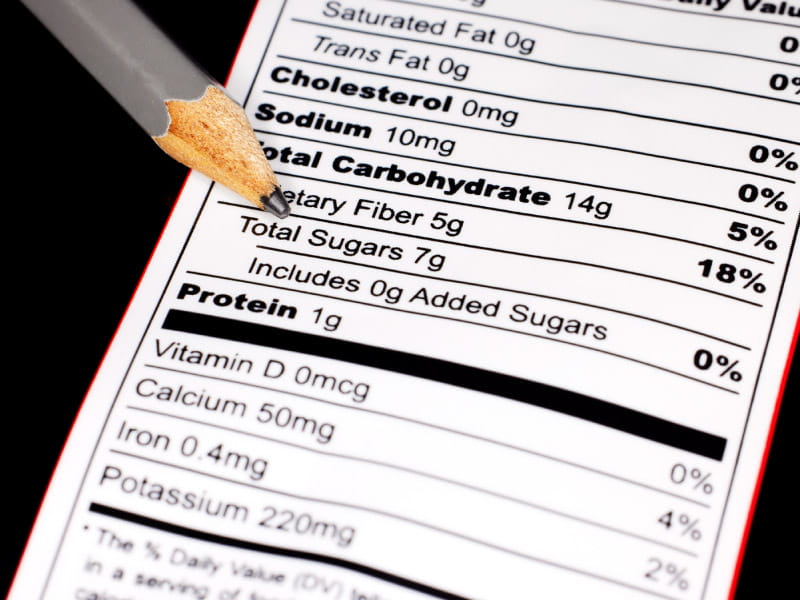

Nutrition labels list added sugars alongside total sugars. You can also scan ingredient lists for items such as syrup, cane juice, corn sweetener or any of those “-ose” molecules.

Once you learn to spot added sugar, look for alternatives. “It might be hard for some people to go cold turkey,” Kris-Etherton said. “But maybe start weaning yourself.”

If you’re used to drinking the largest size of a pumpkin spice coffee drink, switching to the smallest size takes you from 63 grams (nearly 16 teaspoons) of sugar to 25 grams (a little more than 6 teaspoons). Or try black coffee or unsweetened tea for a sugar-free caffeine hit.

If you drink a lot of sugary sodas, switch to unsweetened sparkling water flavored with lemons or limes. If you hydrate with sports drinks, switching to water might help you avoid 35 grams of added sugar (nearly 9 teaspoons) per 20-ounce bottle.

With breakfast cereals, Kris-Etherton gets creative. Her husband is a fan of raisin bran, which she said “does have a fair amount of sugar” at 9 grams, or more than 2 teaspoons, per cup for one popular brand. She mixes it with a sugarless high-fiber cereal to dilute it.

Such cereal subterfuge also works with frosted flakes and corn flakes, she said. Or you can switch to an entirely sugarless cereal and sweeten it with fruit.

For salad dressings, be wary of brands labeled “low-fat” or “fat-free” because they can still be loaded with sugar, she said. As an alternative, she suggests balsamic vinegar, lemon or lime juice, or herbs and spices.

Small steps can add up, Kris-Etherton said. Cutting back “doesn’t mean that you can never have any sugar whatsoever. So, keep that in mind. And then choose wisely.”