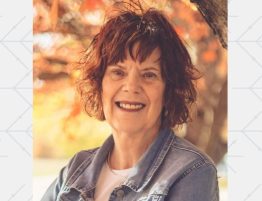

Aubrey Virgin was a healthy, active 2-year-old when she developed a high fever.

Then came a rash that quickly spread over her body. Lymph nodes in her neck swelled. So did her lips, hands and feet. Aubrey cried when her mother, Shannon, touched her.

Shannon rushed Aubrey to a pediatrician near their home at the time in Anchorage, Alaska. The doctor immediately suspected Kawasaki disease, the most common cause of children’s heart disease that is not a congenital heart defect.

Because it resembles many other childhood illnesses, such as measles and scarlet fever, misdiagnosis is common. Left untreated, it has potential life-threatening consequences – 20% to 25% of children develop coronary artery aneurysms, bulges in the arteries that supply blood to the heart.

The doctor sent Aubrey to a pediatric cardiologist and arranged a hospital room.

Aubrey’s bloodwork showed high inflammation. An infectious disease doctor, who previously worked in a clinic for Kawasaki disease patients, came in and took one look at Aubrey and confirmed Kawasaki.

Within 48 hours of the onset of Aubrey’s symptoms, she received intravenous immune globulin, a product made of antibodies given intravenously. It quickly brought down her fever.

Shannon and her husband, Kyle, took turns staying with Aubrey and watching their other daughter, 9-month-old Kyleah. After nearly two weeks in the hospital, Aubrey finally was discharged with a six-month prescription for oral steroids. Every few months, Aubrey had occasional bouts with fever and inflammation, including odd places such as her lips.

Each episode worried Shannon. She found comfort by delving into research and connecting with other families.

“I found the Kawasaki Disease Foundation and joined Facebook groups,” Shannon said. “Several parents whose kids had had Kawasaki commented that things kept popping up with their children afterward as well.”

Despite these occasional flare-ups, Aubrey thrived. She loved to read and be active. She started playing soccer when she was 5 and quickly excelled.

At 6, she participated in her first Alaska Heart Run, a fundraiser for the American Heart Association. She struggled to finish the 5K. The next day, her knee hurt so much she could barely walk. Doctors saw nothing on X-rays, but Aubrey’s blood work showed inflammation. Eventually a pediatric rheumatologist diagnosed her with juvenile inflammatory arthritis – and suspected she also may have a more serious condition.

For two years, Aubrey continued to have flare-ups of pain, inflammation and fever spikes. Doctors told Shannon to start a binder that included every episode, with photos. It grew thicker by the month.

Shannon and Kyle had to fly Aubrey to Seattle every three months to see a specialist. Shannon left her job to oversee Aubrey’s medical needs.

When Aubrey was 8, doctors diagnosed her with a rare systemic autoinflammatory disease called tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome, or TRAPS. It’s hereditary, and testing confirmed Kyleah also has it, though her symptoms are milder. TRAPS is characterized by periodic episodes of fever as well as muscle and abdominal pain, headaches and skin rashes. Aubrey also was diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder.

Now 12, Aubrey is doing well, in part thanks to regular medication that suppresses her immune system. The family now lives an hour northeast of Anchorage, in Palmer, and Aubrey continues seeing a pediatrician, rheumatologist, immunologist and cardiologist.

“My research into Kawasaki disease has led me to believe that it set Aubrey’s immune system into overdrive, and it hasn’t been the same since,” said Shannon. “Because so little is known about the disease and its long-term effects, it’s important that Aubrey continues follow-up care, eats healthy and stays active.”

Aubrey still has painful flare-ups, and the family has been even more diligent about her health since the arrival of COVID-19.

“We toe the line between keeping her safe, but also emotionally and mentally happy,” Shannon said. “She’s full of adventure and very athletic.”

Aubrey’s first Alaska Heart Run didn’t deter her from returning with a team called Kickin’ Kawasaki Disease. Until the event went virtual last year, she was the top individual fundraiser for five years, raising more than $17,000.

Aubrey also is a straight-A student, runs track and field and cross-country, and excels at soccer.

She’s relieved her pain level has finally subsided.

“Medication has helped a lot and I don’t feel so much pain,” she said. “The only thing the medication can’t help is the mental challenges. Sometimes I get overwhelmed by things, but I’m learning how to control that.”

Over the summer, Aubrey ran the grueling Mount Marathon, a 5K race with a 3,000-foot elevation gain. She finished in the top 10 for juniors, which included girls up to age 17.

“It was exhilarating,” she said. “Running feels natural and fun.”

Aubrey, who also is a skilled hunter, hopes to work in wildlife conservation.

“I like learning about everything in nature.”

Stories From the Heart chronicles the inspiring journeys of heart disease and stroke survivors, caregivers and advocates.

If you have questions or comments about this story, please email editor@heart.org.