Cynthia Felix Jeffers was a baby when her 12-day-old sister died from a congenital heart defect.

She was 22 when her brother, a week shy of 20, died from the same condition.

Cynthia, meanwhile, grew up in New York City being told there was nothing wrong with her heart. Doctors insisted her shortness of breath was caused by asthma. Even though inhalers provided no relief, tests showed her heart was fine.

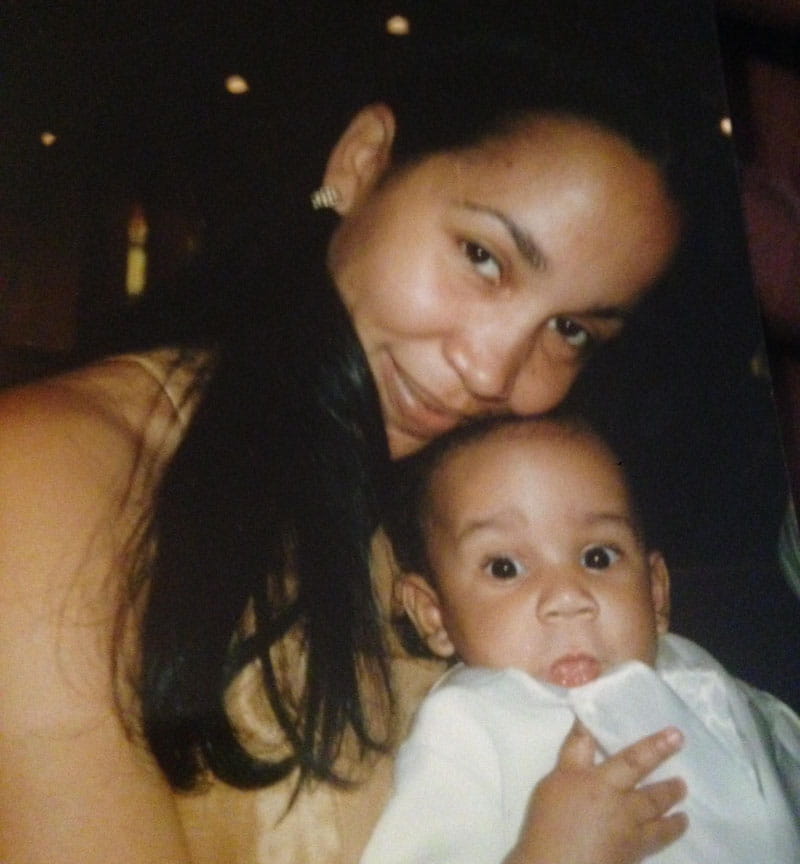

At 27, she had a son. Elijah was nearly 1 when his pediatrician detected a heart murmur. Further testing revealed he was born with a version of the same problem that claimed the lives of her siblings.

Elijah had a hole in the center of his heart called an incomplete atrioventricular septal defect, or AVSD. The problem can affect circulation.

“It felt like a death sentence,” Cynthia said.

It wasn’t, though, because of a crucial difference in the diagnosis.

Her sister and brother had “complete” defects that affected all four chambers. Elijah’s defect was incomplete. Doctors fixed his problem through a minimally invasive heart surgery that left only a tiny scar. Within a week, he was up and about.

All the while, she still found herself short of breath. At times, she could barely walk to the end of the street, let alone climb stairs. On several occasions, she passed out. Sometimes her fingers turned blue. “A lot of things were happening that didn’t make sense,” she said.

Ultimately, she made an appointment with a cardiologist who specializes in adults with congenital heart defects.

He determined that Cynthia – just like Elijah – had an incomplete AVSD.

“I was shocked but also felt a sense of relief, because I knew I wasn’t crazy,” she said. “The doctors had dismissed me and my symptoms for so long that I had begun to doubt myself.”

About 10 years after Elijah’s surgery, a congenital cardiac surgeon performed the same minimally invasive heart surgery on Cynthia. Unlike her son, she didn’t have an easy recovery. She had very little energy. She twice had to have fluid drained from her lungs.

When insurance denied cardiac rehab, Cynthia started riding her exercise bike and taking walks around the neighborhood with her husband, Edwin. Within a year, she noticed a big difference in her stamina. Two years later, she could walk for hours without feeling fatigue.

“I could walk my son to school without stopping to rest,” she said. “That was big for me.”

Years later, Cynthia’s heart rate began to spike as high as 250 to 270 beats per minute. She passed out several times, once landing so hard that she broke her collarbone, another time breaking a thumb.

She was diagnosed with supraventricular tachycardia, a condition that causes a rapid or chaotic heartbeat. She underwent several ablation procedures to essentially destroy the electrical pathways that caused the irregular heartbeat.

The arrhythmia may have been caused by the scarring in her heart from her heart surgery, said Dr. Adam Small, the cardiologist specializing in adults with congenital heart defects who treated Cynthia.

“When the electricity encounters a scar, its course gets diverted, and that can be the birth of an arrhythmia, where the electrical system sort of goes haywire because it’s trying to navigate around or through scars,” he said.

For now, Small and his colleagues manage Cynthia’s condition with medication. They also monitor her heart rate with an implantable loop recorder, a thumb drive-sized device that sits under the skin. She also has an echocardiogram twice a year to monitor her tricuspid valve, which doesn’t close property. As a result, blood leaks back into her heart’s right upper chamber.

Cynthia wonders how things might be different if she had been diagnosed as a child. She points to Elijah, who is now 25, a healthy and athletic physical education teacher. “He hasn’t let it limit him in any way, and I attribute that to the fact that we caught it very early,” she said.

Determined to raise awareness about congenital heart defects, Cynthia became involved with the American Heart Association. She has done several Heart Walks and participated in the organization’s Go Red for Women campaign, sharing her story and hosting events for Hispanic women.

Her message: “As caregivers, us women often put ourselves last and ignore the pain, and a lot of us in the Hispanic community dismiss things. Through education and advocacy, we can save lives.”

After her heart surgery, Cynthia got a tattoo on her upper back. One side has an image of the squiggly lines from her electrocardiogram. The other side shows Elijah’s EKG reading. Those drawings are bridged by the word “faith.”

“The connection between us is very meaningful,” she said. “We both survived this together and came out stronger because of it.”

Stories From the Heart chronicles the inspiring journeys of heart disease and stroke survivors, caregivers and advocates.