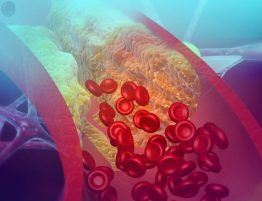

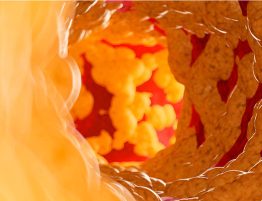

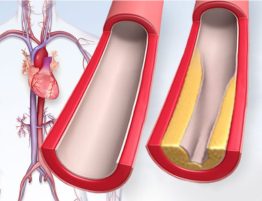

LDL cholesterol – the so-called “bad” cholesterol – is known to narrow arteries, which can lead to heart attacks and strokes. It’s also now suspected of contributing to venous thromboembolism, new research suggests.

The preliminary study, presented Tuesday at the American Heart Association’s Vascular Discovery Scientific Sessions, looked at genes and proteins that might influence venous thromboembolism, or VTE, a condition that causes potentially dangerous blood clots to form in the legs or arms that can break free and travel to the lungs.

Researchers studied DNA from people with and without VTE who took part in two large programs, the Department of Veterans Affairs’ Million Veteran Program and UK Biobank. After testing for 13 million genetic variants and finding 26,066 cases of VTE, researchers identified several new factors that might cause VTE, including a protein called plasminogen activator inhibitor 1.

They also identified LDL cholesterol as a risk factor for VTE.

“We don’t usually think of cholesterol as being important in venous disease, but our work on this study provides strong evidence that it may be predisposing people to venous thrombosis,” said one of the study’s lead authors, Dr. Scott Damrauer, a vascular surgeon at the Corporal Michael J. Crescenz Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Philadelphia and an assistant professor of surgery at the University of Pennsylvania.

Damrauer said the study raises the possibility of using cholesterol-lowering statins to specifically reduce VTE risk, since past research suggests treating cholesterol with statins can also help prevent blood clots.

Dr. Geoffrey Barnes, a cardiologist and vascular medicine specialist who was not involved in the new study, said more research is needed. Even so, he called it a significant study that could help identify potential new targets for prevention and treatment.

Venous thromboembolism is an important cause of cardiovascular death and disability in the United States and worldwide, said Barnes, an assistant professor at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. “So anything we can do to understand why it occurs and how to better treat it is really important.”

About an estimated 1 million people in the U.S. were treated for VTE in 2014, based on the latest statistics from the American Heart Association. VTE can occur at any age but is most common in adults 60 and older. It is a leading cause of preventable death among U.S. hospital patients, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Damrauer called for more research to explore how VTE can best be detected and treated.

“This study shows how we can use genetics to try to more accurately understand who will go on to develop venous thromboembolism and who will not,” he said.

Damrauer said future genetic research will benefit greatly from huge medical databases such as the VA Million Veteran Program study, an ethnically diverse group of veterans who voluntarily gave their health information. The program provided genetic data from more than 11,000 VTE patients for the current study, Damrauer said.

“Because of this innovative program started by and funded by the VA, we were able to assemble the largest study of venous thromboembolism to date, with about 10 times more people than previous studies,” he said.

“Large projects like this will push the power of discovery and allow us to better understand the genetics of a whole host of diseases. I think ultimately, these projects will change how we look at health.”

If you have questions or comments about this story, please email [email protected].