Every year, the American Heart Association compiles statistics that tell the story of how cardiovascular disease affects the lives of people in the U.S. and around the world. This massive, monthslong endeavor takes a team of experts who produce a book-length report covering so many topics they require chapter headings.

But it didn’t start out that way. Nearly 100 years ago, it began with just one woman. A woman who loved to play with numbers, almost as much as she loved to play baseball.

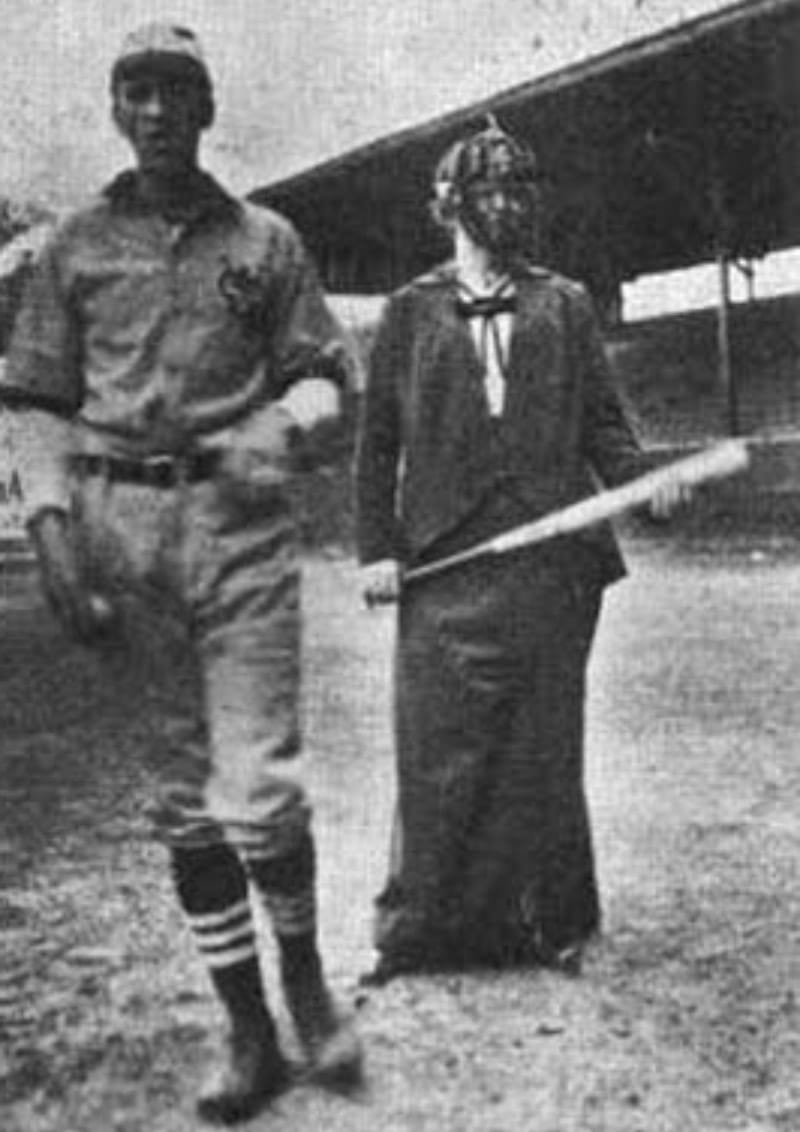

Jessamine Whitney – who produced the earliest statistical reports on heart disease mortality found in the AHA archives – grew up following her dad to baseball games in upstate New York, carrying with her a tiny rocking chair so she’d have a place to sit. Old newspaper stories describe a baseball-loving young math whiz whose dual passions resulted in a career as an internationally recognized statistician and a hobby in sports analytics, long before that phrase came into being.

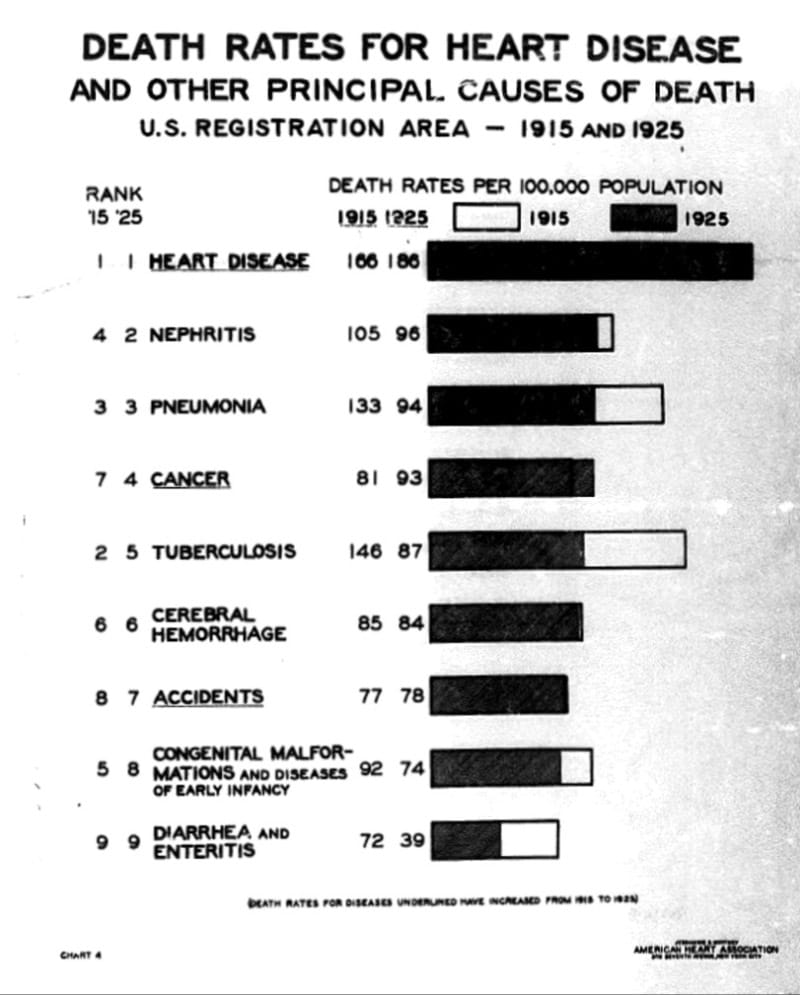

Dr. Seth Martin, a cardiologist at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore and chair of AHA’s 2024 statistics update published Wednesday, was fascinated by Whitney’s pioneering efforts in both fields. He noted that her first statistical report for the AHA, published in 1927, included mortality data on heart disease, tuberculosis, cancer and pneumonia and was 30 pages long.

“I was really intrigued that it was a report from a single author,” he said. “Now we have a very large committee that writes the documents, and they are hundreds of pages long.

“To do this all by herself and also at this time, when modern computing didn’t exist, was really incredible,” Martin said. “I’m trying to imagine all the manual effort that may have been required to tabulate all these charts and all the numbers. She seems to have been a really remarkable woman for sure.”

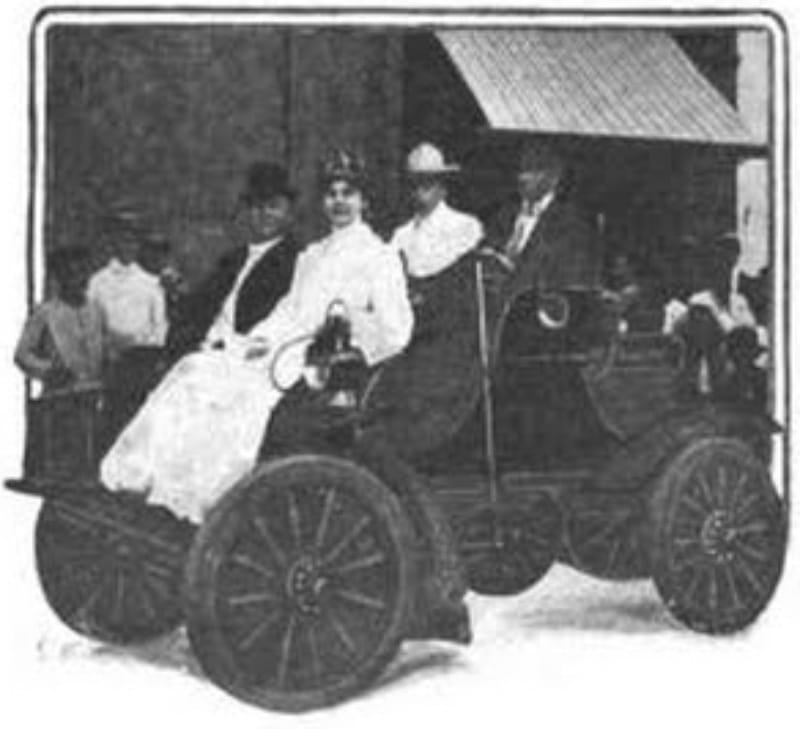

Whitney was a woman of many firsts. She was reportedly the first woman to drive a car in Puerto Rico. She was the first and only woman selected in 1929 as an American delegate to the International Conference on the Classification of Causes of Death, which met in Paris every 10 years.

Whitney studied mathematics and economics at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, earning her bachelor’s degree in 1905. She worked briefly for the U.S. Census Bureau, and, in 1918, she became the statistician for the National Tuberculosis Association, where she worked for 22 years until she had a fatal heart attack at her desk in 1941.

Her work for the AHA took place after the two health organizations created what a National Tuberculosis Association report called a “plan of co-operation” in 1926, while they briefly considered a merger, sharing office space, staff and funding.

As does AHA’s current statistical update, Whitney’s early reports ranked the causes of death and found heart disease to be at the top. That much has not changed, Martin said. He came across Whitney’s work while doing research for the AHA’s centennial statistical update.

His interest in Whitney was further piqued when he searched her name online and discovered a picture of her in a baseball uniform. Whitney had become so well known for her analyses of baseball box scores that she was invited in 1914 to be an umpire at a charity game.

“She got a lot of experience compiling statistics with baseball players and teams and trying to predict winners,” Martin said. Whitney analyzed the statistics during her free time, when she wasn’t doing social research on who was dying from tuberculosis and why.

“Those skills made her uniquely qualified to compile these statistics for the American Heart Association,” Martin said.

Whitney’s early work did more than provide interesting facts about heart disease mortality, he said. It likely helped shape the mission of the AHA, as do the reports that evolved into the voluminous analyses produced today.

“At its core, the statistical document can be viewed as being the heart and soul of AHA,” Martin said. “It shows us how things change from year to year and where AHA should make investments, where priorities should be in terms of advocacy and research. It’s an important guiding light.”

Jessamine Whitney was the first to make it shine.